When it comes to small-town Georgia high school football, it was a familiar scene.

On Dec. 16, 2006, the Dublin Fighting Irish hosted Charlton County for the GHSA Class AA championship. Although the game didn't start until 4:30 p.m., fans began tailgating at 6 a.m. The area surrounding the Shamrock Bowl, where the Fighting Irish play, was so packed that the team needed a police escort just to get across the street from their pregame meal. Approximately 11,000 fans packed the stadium to watch the game, which ended in a 13-13 tie that crowned co-state champions.

"It was an unbelievable day, an unbelievable game-day experience," said Dublin coach Roger Holmes, who is in his 18th season with the Fighting Irish.

That's just one example that shows how high school football is so important to small towns. Without the option of nearby big-city activities, and the large populations that make it impossible to know everybody, small town communities are inherently more tightly knit.

That means high school football plays a big role in bringing everyone together and helping the economy. And if the small-town team isn't winning, it sometimes creates hard times for athletic programs trying to fund activities.

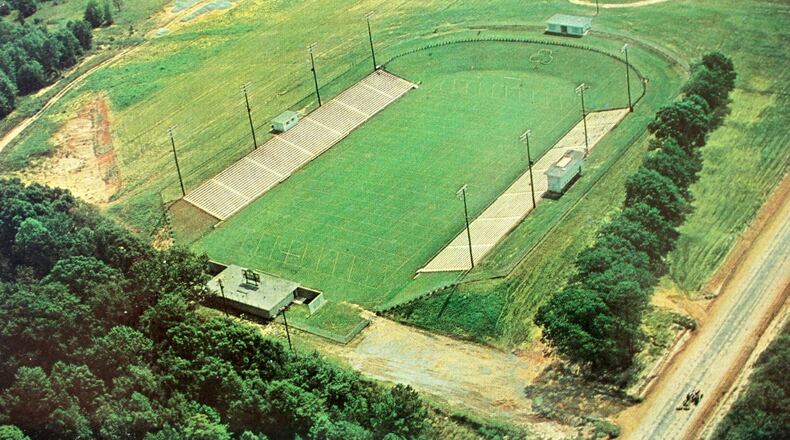

Although Dublin High is now one of four high schools in Laurens County, it's still a small town — population 15,889 in 2017, according to the Census Bureau — and it used to be the only school in town. After the Fighting Irish won back-to-back state titles in 1959-60, a group of citizens took out personal loans from the bank, and others chipped in whatever they could to fund construction for the Shamrock Bowl, which was completed in 1962.

"That's just the type of investment in the community that small-town people make," Holmes said.

Football tradition goes way back at Dublin, which opened in 1897, with a history that dates back to at least 1919, according to the Georgia High School Football Historians Association. As a result, the Fighting Irish have a built-in fanbase that's common among small towns.

"In a small town, the town itself is usually not very transient," Holmes said. "People who grew up there tend to stay there, and that in itself builds a long alumni base. For a lot of the adults here, their fondest memories are the days and times they had at Dublin High School. There's a lot of community pride here."

In Quitman — population of 3,718 — Brooks County is the only school, and coach Maurice Freeman notes that the perennially successful team helps bridge the gap between different races and how they interact.

"They meet on the same platform and accept each other because everyone is having a good time together," said Freeman, who is in his 17th overall season at Brooks County, which spans two different stints (1994-97; 2008-present). "Just like anywhere, there are black and white churches, but at the games they're all in the same bleachers, giving high fives and cheering for the same team."

The Trojans have never endured a losing season under Freeman, who delivered the program its only state title in 1994 when the Trojans beat Manchester to claim Class A. That's important for a small-town team, because if it's losing, attendance drops.

"The majority of things you have to buy for athletics comes from gate receipts," said Freeman, who also serves as Brooks County's athletic director. "More fans go to football games than baseball, softball, etc. Speaking from an athletic director's point of view, we make most of our money through football, so we have to be successful to feed all of our other sports. If we weren't winning, the athletic program would be broke and borrowing money just to survive."

Rabun County, with a population of 16,602, has only one school, named after the county and located in Tiger, population of just more than 400. First-year coach Jaybo Shaw, who succeeded his father Lee Shaw, said the town shuts down for football on Friday nights. Lee was a 1984 Rabun County graduate who quarterbacked the Wildcats and coached there from 2012-18

"It means the world to our community," Jaybo said. "We preach family as a team, but Rabun County, as a whole, is a family. It means more than a bunch of kids playing on Friday night, and it's hard to put into words."

During the 2017 season, Shaw, who then was an assistant on his father's staff, saw first-hand what the football team could do for the community from a business standpoint. The Wildcats benefitted from a fortuitous turn of events when weather postponed the state championships, which led the GHSA to move the title games from Mercedes-Benz Stadium to the home of one of the participating teams. The Wildcats won a coin toss, and thus got to play host to the Class AA title game against Atlanta's Hapeville Charter. They also had played at home in the semifinals against Brooks County — located 330 miles and five hours away — the week before.

"We had so many people coming up to Rabun County checking into hotels and spending their money," Shaw said.

Now, the small-town Wildcats are gaining national attention because of sophomore quarterback Gunner Stockton, who's the No. 2-rated dual-threat quarterback in the country for the class of '22, according to 247Sports.

"That's been amazing for Rabun County," Shaw said. "What's really cool is Gunner was born and raised here. It just brings more exposure and attention this way and helps our community and the school system. It's hard to put a measure on how much a team can do for a small-town community."

With No. 4 Dublin, No. 5 Rabun County and No. 7 Brooks County all ranked and considered state-title contenders, times are good for those small-town teams.

"The community is excited, and we have a chance to put together a really great year," said Dublin's Holmes.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured