Whose cultural values should schools promote? Who decides?

University of Georgia professor and frequent Get School contributor Peter Smagorinsky was recently awarded the 2018 International Federation for the Teaching of English Award for his internationally distinguished contributions to scholarship in the field of English in Education.

As such, Smagorinsky has been traveling abroad but managed to write this piece for the blog, which touches on our earlier discussion this week of the appropriate response to the racism in the acclaimed "Little House on the Prairie" series of children's books

By Peter Smagorinsky

Amidst the cornfields of central Illinois resides a city that goes by the curious name of Normal. You might be interested in how it got this name, and why its history matters to schooling today.

Normal, Illinois, was originally called North Bloomington. It was renamed in 1857 when the state board of education chartered Illinois State Normal University and it was awarded the bid to host the new institution. The name was later shortened to Illinois State University, located in the city of Normal.

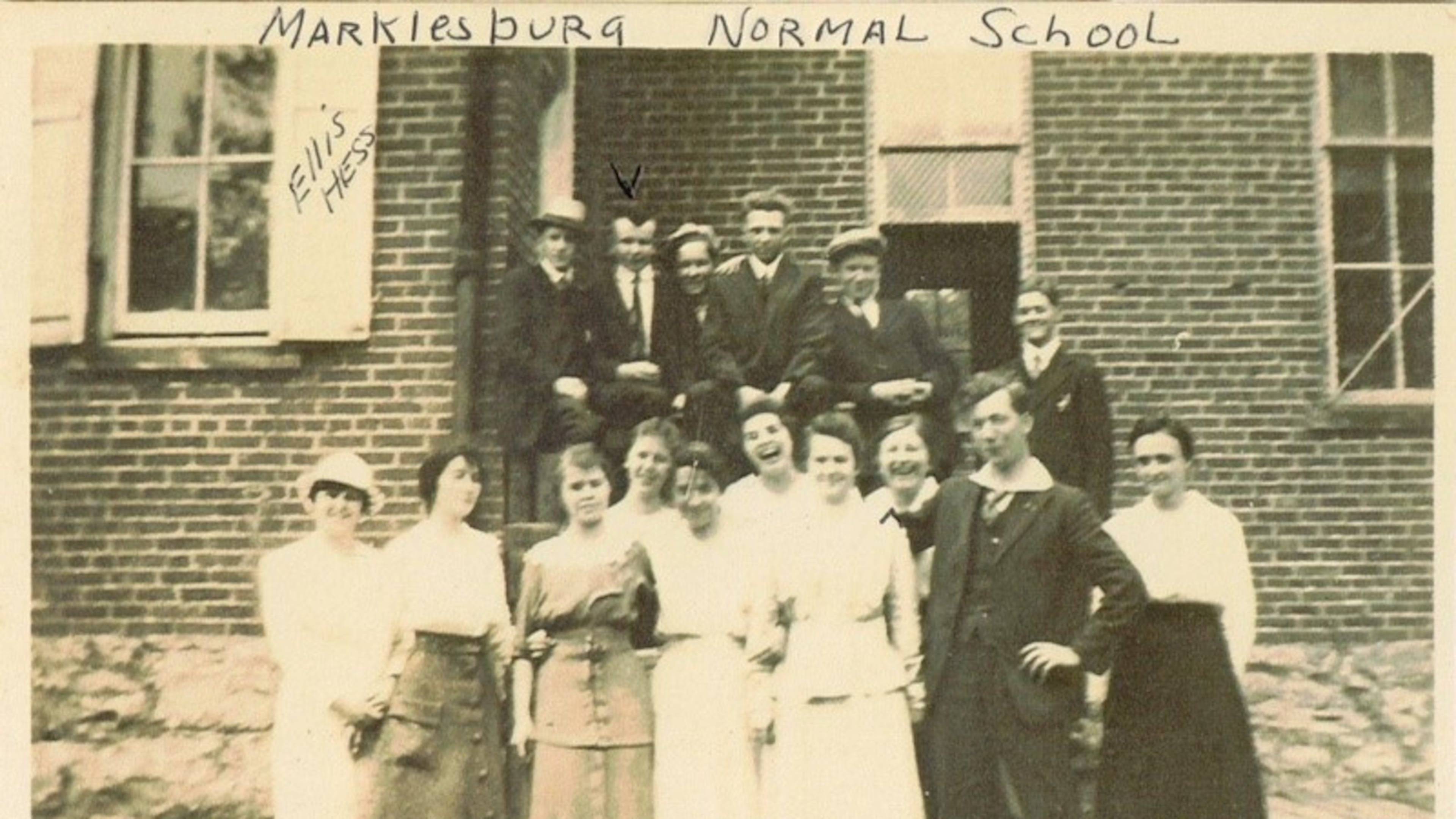

A Normal school exists to train young people for a profession in teaching. Established in France in 1685 as École Normale, the idea of a college especially for teacher education was first adopted in the United States in 1823. Although Illinois State and many other universities now are comprehensive in scope, many began with the specific mission of preparing teachers.

The idea behind a Normal School was to instill norms in teachers, students, schools, curriculum, and instruction. In the face of diversity in the industrialized workforce, the intention was to use education to provide a relatively singular culture within which teachers should structure student’s growth toward national citizenship. This culture would embody dominant values, ways of speaking and interacting, thinking, and entering public life, and served as the foundation on which schools should function.

I would call this a fundamentally conservative approach to the training of teachers and to the conduct of schools. That is, teacher education was designed specifically to conserve and perpetuate dominant, established values and their accompanying ways of behaving, working, and engaging with society. This approach was consistent with other ways of normalizing people in an expanding nation that included what was then a varied collection of immigrants, native people, ethnic groups, political perspectives, and other divergent types.

I have taught in what were once called Normal Schools since 1990. They are now neither called Normal Schools nor include normalizing teachers and students to the dominant culture’s values as a principal mission. If anything, colleges of education and other teacher education units have moved in more recent times in the opposite direction.

My College of Education at the University of Georgia is now typical of such schools of teacher education. A commission launched in 2015 introduced its goals as follows:

“the College of Education serves the statewide community. . . . as the state population is becoming increasingly diverse, it is imperative that the colleges develop and implement individual as well as organizational changes that further reflect the overall needs of the population it serves. . . . we provide recommendations of potential initiatives that would facilitate increased diversity and inclusiveness at the college. . . . diversity is loosely defined in this report to include race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, disability, social class, immigration status, language skills, generational level, geographic location as well as the interaction between these respective variables. . . . the recommendations highlight potential structures, policies, leadership positions, and techniques that would facilitate a stronger focus on diversity.”

My point is neither to defend nor critique this major change in charge; I'm sure commenters will provide their own analysis, and I encourage you to add your own. Readers' responses to the recent Get Schooled essay on the Association for Library Service to Children's decision to drop Laura Ingalls Wilder's name from their book award because of its overtly racist views toward native people suggest that the revised mission of the modern COE will be met with disfavor, at least by some.

My purpose in sharing both this national history and more recent shift in priorities is to puzzle through this major shift in emphasis in how and why teachers are taught to teach, given how contentious the nation has become over whose nation it really is and how its many and varied peoples and cultures can coexist as a society.

Colleges of education, and their diversity agenda, are at odds with both national movements toward the sort of standardization inherent in the notion of a Normal School, and a current political environment that is conservative in nature. I am writing this essay from the United Kingdom, where I attended an international education conference. A major theme of participants from the U.S., Australia, and the UK is that our governments and many among our citizenry are committed to imposing one set of norms on all teachers and students through standardized curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

Each of these embodies an ideology that represents the values of the European-descendant majority, and often males from that demographic. Meanwhile, teacher educators tend to share the values of the UGA COE commission I quoted above, promoting diversity and resisting centralized and standardized notions of what to value in American society.

I work within these tensions, often with frustration over the difficult effort to find resolution between the general need for a society to have some core from which to proceed as a nation, and the concurrent need to accommodate people whose communities do not align well with the structures and practices provided by people comprising the dominant cultural group.

This set of tensions reflects broader conflicts across the nation. Should educational policy be standardized in Washington, D.C., or serve the interests of local communities only? Each involves perils. I have objected often to policies constructed by people who’ve never taught. These systems have been imposed on the nation in such forms as No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top, generated in turn by a Republican and then Democratic national administration.

But I would also object to thoroughly local policies that impose their norms on all teachers and students, movements that could easily prove highly discriminatory. I know this from having attended segregated schools as a Virginia schoolboy, where political and educational leaders attempted nullification efforts to resist the federal order to integrate.

I’m not trying here to win this conflict. Rather, I’m looking at the work that we do in teacher education, recognizing that it has shifted dramatically from its original mission, and trying to place it into historical context, one that has always felt a tension between establishing one norm, and attending to many, in thinking about what’s best for a nation. Like many COE faculty, I lean toward many norms, although not all, because I reject norms based in hate and violence.

I have always rolled my eyes at the “celebrate diversity” slogans that often come from educators. Educating people from cultures with different value systems is difficult, challenging work. It shouldn’t be trivialized to posters with different colored kittens snuggling together on a pillow. Some of those kittens have pretty sharp claws, and like all cats, each will eventually go its own way.

Should schools, and schools of education, normalize all to one set of values under the assumption that it’s even possible? Federal education policies suggest they should; and many local communities believe the feds should let them alone to establish their own educational monocultures. Colleges of education meanwhile promote diversity as a value. It’s a conundrum to be sure, one that will undoubtedly trouble me and my descendants in this profession for many years to come.