Top university tells new students: No trigger warnings or intellectual safe spaces

A letter to freshmen from the University of Chicago is reigniting the discussion over trigger warnings in classes and safe spaces on campus. In its letter, the prestigious university cautions:

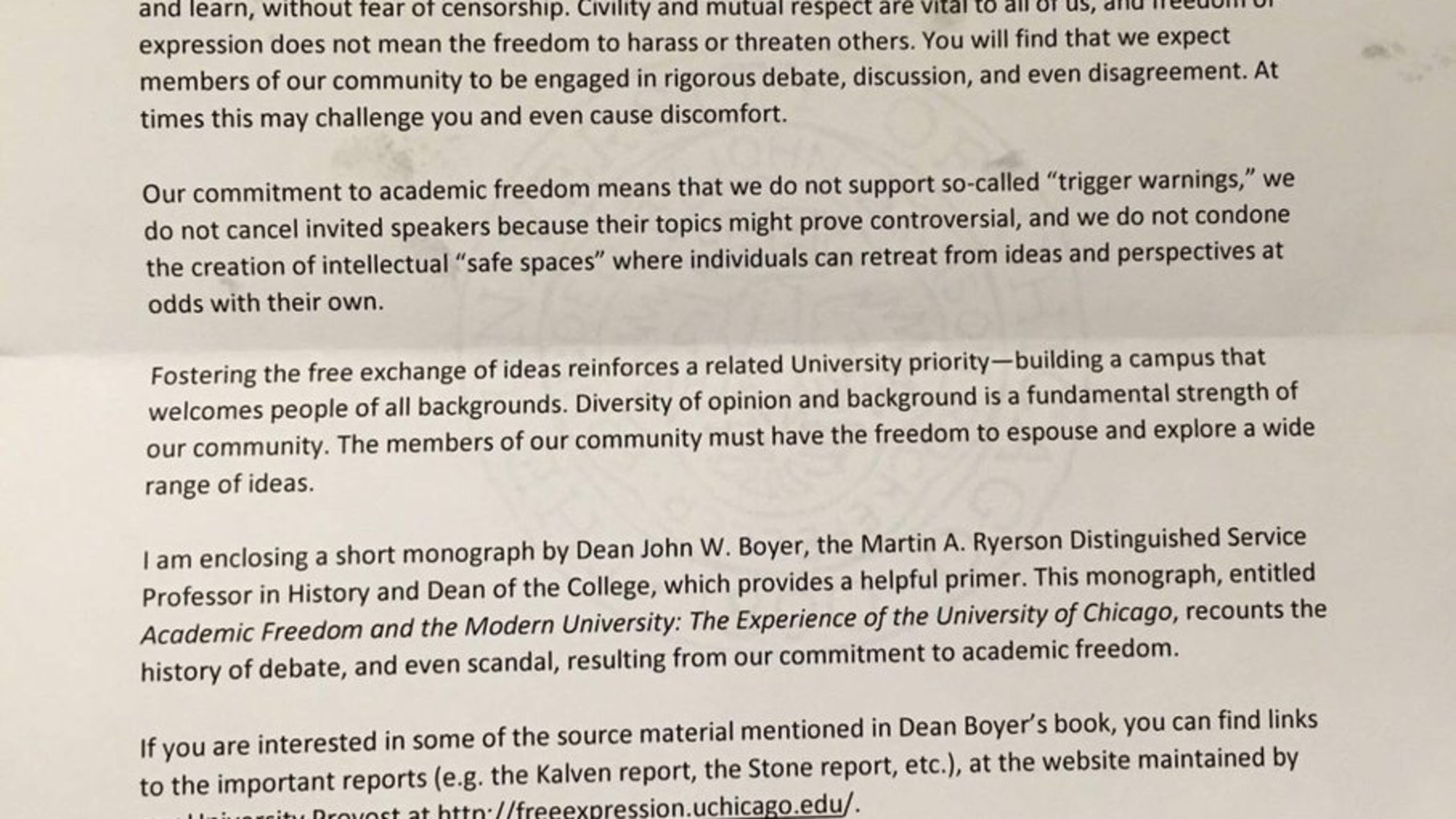

Our commitment to academic freedom means that we do not support so-called "trigger warnings," we do not cancel invited speakers because their topics might prove controversial, and we do not condone the creation of intellectual "safe spaces" where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own.

The university is not the first to questions trigger warnings and safe spaces. But the practices have support.

Some professors employ trigger warnings to alert students there may be material in the class that could be upsetting to victims of abuse or trauma. You can read a defense of trigger warnings here by a professor who explains, "At least some of the students in any given class of mine are likely to have suffered some sort of trauma, whether from sexual assault or another type of abuse or violence. So I think the benefits of trigger warnings can be significant."

Safe spaces entered the vernacular as a result of recent Black Lives Matter protests where student protesters sought refuges on campus where they could meet and find strength through others sharing their life experiences. In this essay, Morton Schapiro, president of Northwestern University, said giving students in the Black Lives movement a safe space was no different from the longstanding Hillel house for Jewish students or the Catholic Center for Catholic students.

The University of Chicago stance is garnering praise online, but I found a dissenting response from a professor. Here is an excerpt:

Our first reaction to expressions of student agency, even when they seem misguided or perhaps frivolous, should not be to shut it down. Ableism, misogyny, racism, elitism, and intellectual sloppiness deserve to be called out. That's not a threat, that's our students doing what they're supposed to as engaged citizens of an academic community. This year, we should challenge ourselves to quit fixating on caricatures and hypotheticals and instead acknowledge the actual landscape of teaching and learning in all its messiness and complexity. When we act out of fear, we do harm. When we assume the worst from our students, that's what we often end up getting-from them and from ourselves. We can do better than this.