Scientists do the math to show how large events like March Madness could spread coronavirus

Critics who contend canceling March Madness and other large events to prevent the coronavirus is overkill may change their minds after reading the math behind it.

Joshua S. Weitz is a professor of biological sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology and founding director of the Quantitative Biosciences Ph.D. program at Georgia Tech. His co-authors on this fascinating column are Richard Lenski, National Academy of Sciences member from Michigan State University, Lauren Meyers, infectious disease expert from UT-Austin, and Jonathan Dushoff, infectious disease modeler from McMaster University.

Here, they explain a mathematical model that illustrates why banning large events helps in the midst of an epidemic.

By Joshua S. Weitz, Richard E. Lenski, Lauren A. Meyers, Jonathan Dushoff

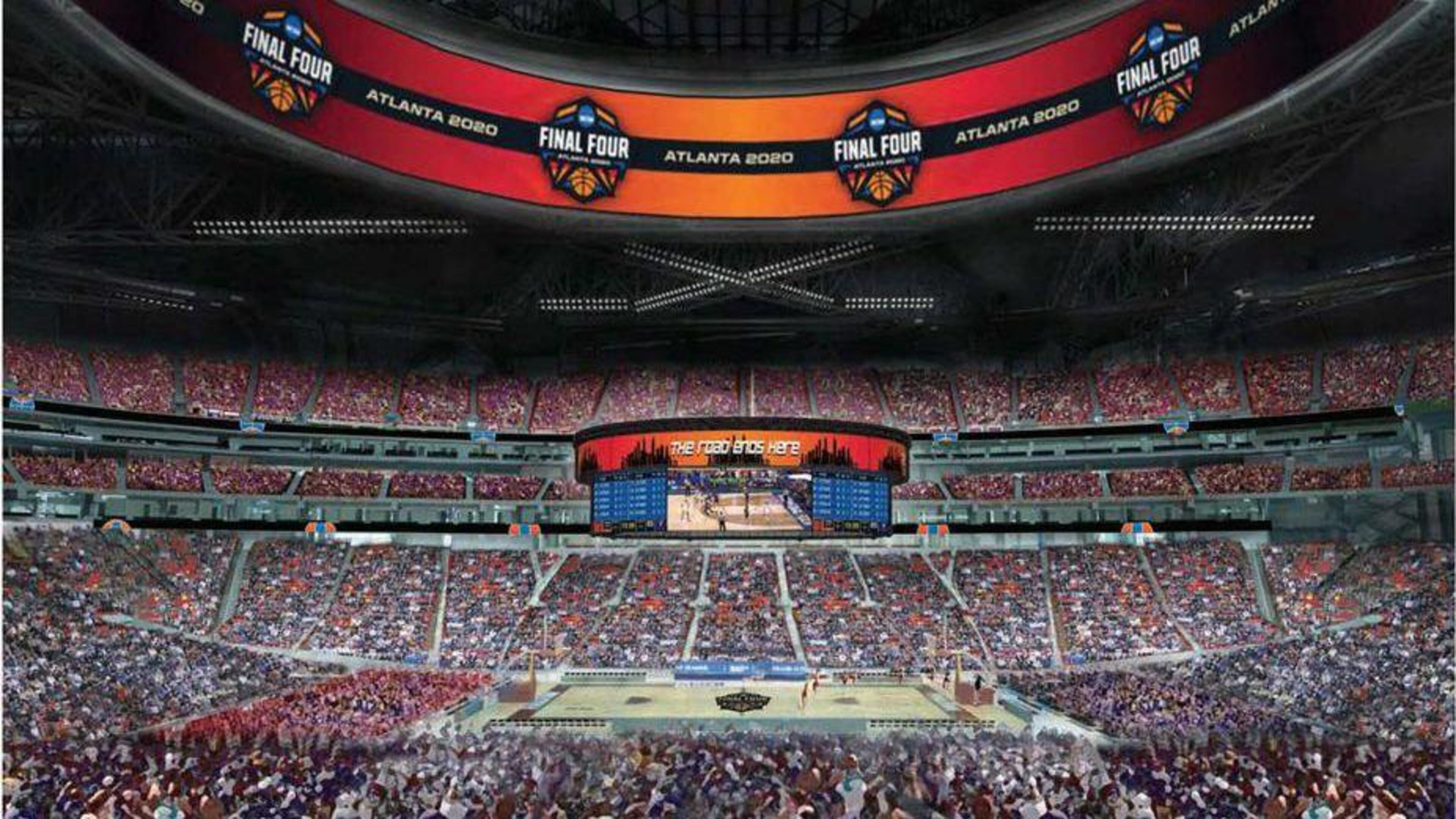

More than 75,000 fans were planning to travel from around the United States (and beyond) to crowd the Mercedes Benz stadium in downtown Atlanta on April 4 and April 6 to watch the NCAA Basketball Championship and the culmination of March Madness. But, on Wednesday, the NCAA restricted the presence of fans at all tournament games in light of the growing COVID-19 threat.

We believe this was a prudent decision and that similarly painful decisions will be made in the weeks ahead.

It comes down to simple probability.

Even if only a few individuals have COVID-19, the collective chance that one (or more) infected people show up at a large gathering can rapidly approach 100%.

For context, as of March 11, 2020, the CDC reported a cumulative total of 938 confirmed COVID-19 cases nationwide across 39 states including the District of Columbia. On the same day, health departments across the country reported a cumulative total of 1,100 lab-confirmed cases with more than 500 pending (@COVID19Tracking on twitter). And, these numbers likely underestimate the true prevalence of disease.

Based on data from Wuhan, China and Italy, the number of new cases is expected to double approximately every week if social distancing and other control measures are not enacted. Hence, the 2,000 or so cases right now (assuming an approximately 2:1 undercount) may rise to 20,000 cases by early April.

Moreover, COVID-19 seems to be quite mild and possibly asymptomatic in some people, making their infections very hard to detect. Indeed, some experts (including Alex Perkins of Notre Dame University) speculate that cumulative incidence may be 20,000 cases already.

This would mean there may be upwards of 200,000 circulating cases nation-wide by early April. The super-spreading event at a recent Biogen conference in Boston (with more than 70 confirmed cases) provides a stark demonstration of potential risks of large gatherings. What then is the chance that one (or more) fans will enter an arena already infected with COVID-19 for a night of hockey, basketball, soccer, wrestling, or music?

To answer this kind of question, we actually calculate the opposite, returning to the example of March Madness and asking: what is the chance that none of the 75,000 attendees is infected?

Let’s start by thinking about just one of them. If 20,000 of the 330 million people in the United States are sick, then each person has a 99.994% chance of being disease-free. In betting terms, the odds are 16,500:1 in our favor. While that sounds good from an individual perspective, the collective risk is very different.

In this scenario, the probability that all 75,000 attendees would have entered Mercedes Benz stadium disease-free is like placing 75,000 bets each at nearly certain odds. Sure, you’ll win most of the bets. But the probability that you will win every single one of those bets is extremely low. To calculate it, we multiply the winning probability (1-1/16500) by itself 75,000 times and find that there is approximately a 1% chance that we win every time. In other words, the chances that one or more attendees would have arrived infected with SARS-CoV-2 is 99%.

All it takes is just one “losing” bet. The bigger the crowd, the more chances there are to lose. Given these odds, we believe the NCAA’s decision was warranted.

The negative impacts of cancelling large-scale events are real – and include social and economic hardships that are often disproportionately felt by those unable to absorb a loss of income. Yet, such costs should be weighed against the potentially immense human and economic costs of fueling the spread of a pandemic disease throughout the United States and beyond.

The recent cancellation of SXSW in Austin, suspension of the NBA season, and closures of several university campuses are among a growing list of costly measures taken to minimize risk locally and globally.

As the cases of COVID-19 continue to climb, the size of what is considered a tolerably “large” gathering will shrink. The basic math may point cities, communities and schools towards difficult and unpopular decisions to protect public health. At this point in the unfolding pandemic, the cancellation of large events will help to protect us and our loved ones and slow the global expansion of the disease.

We can all do our part by washing our hands, reducing the number and closeness of our social interactions, isolating ourselves if and when we feel sick, and stepping away from mass gatherings until we find ourselves on the other side of this epidemic threat.