Tim Mullen has taught seventh grade life science in Gwinnett County Public Schools for 24 years and is the author of the book, "Stop Blaming and Start Talking: Developing a Dialogue for Getting Public Schools Back on Track." He is a former president of the Professional Association of Georgia Educators.

In this op-ed column, Mullen discusses House Bill 338, better known as Nathan Deal's Plan B, which comes in the wake of the Opportunity School District's defeat in November.

By Tim Mullen

There is a lot of talk about how Gov. Nathan Deal and the Georgia Legislature are going to address "failing schools."

“Something must be done to help the students” is the usual rhetoric. A recent AJC article quoted a parent saying his “children are fine”; “he feels empathy for students in under-performing schools”; “you hear about them on the news,”, and “nothing will change if it’s left up to teachers and principals. Somebody needs to step in and help them.”

The governor wants to be that somebody. Last week, we heard about Deal's Plan B, which echoes his failed Opportunity School District proposal.

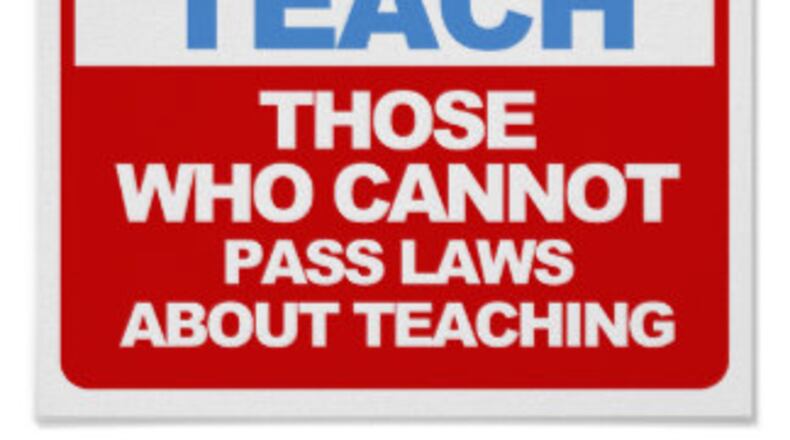

I am a teacher. Although I do not teach in a "failing school," I have heard the same message from parents, media, and politicians for years: “Teachers, it is your fault children are not learning.”

However, problems impacting student performance are not confined to only those schools designated as "failing." Instead, the problems are complex and in every school in Georgia, but the influences negatively impacting student performance are concentrated in the schools labeled "failing."

So what really are failing schools? In order to determine if a school is failing, and why, there must be an articulated and relevant goal that is not met by some accurate measurement. In order to arrive there, we must ask, and honestly discuss, several larger questions:

Why are schools “failing” in the first place? Why do some schools “fail” year after year, while others do fine?

Poverty is a factor, but there’s much more that needs to be in the dialogue, including the impact poverty often has, such as poor nutrition, minimal medical care, environments that deny physical and emotional safety, and an atmosphere that undermines positive academic experiences. Teachers can do only so much when the students come to school hungry, unloved, neglected, abused, and/or homeless.

When students fear for their safety at home, when parents are going through a bitter divorce, or when a single parent working two jobs doesn't have time to help the child with schoolwork, it will be difficult for the student to focus and learn. In Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, what we think of as “education,” is a level 5 need, which means the needs of levels 1-4 must be sufficiently met before cognitive growth can occur. However, the basic needs are not often met in economically disadvantaged areas.

What is the purpose of public schools? Is it to raise and educate children to be good citizens who contribute to society? If so, what does “contribute to society” mean? Should the goal of “non-failing” schools be for students to learn detailed standards listed by the Georgia Department of Education, or are there more intangible, yet important factors?

What measures are we using to assess performance, and do they actually measure anything? Schools in Georgia are judged based on the College and Career Ready Performance Index, which is heavily based on student test scores (Milestones, End of Course Tests and others).

If the purpose of schools is to create educated, well-rounded, and successful citizens, let’s define what that is and proceed. However, when the CCRPI and teacher evaluations all need data for comparison, the focus will be on the tests, no matter what anyone says. Principals and teachers feel pressure for students to perform well on tests. But it is not always clear what those tests are measuring.

The rhetoric about "fixing" failing schools is only political posturing until the real discussion about what is happening in the communities and homes of those students is addressed. EVERY CHILD should have access to equitable education – that was the intent of the Education and Secondary Education Act originally authorized in the 1960’s (now called Every Student Succeed Acts), and that is the belief of EVERY TEACHER I ever met. However, there are many influences impacting schools that are not being considered by these tests. The teachers cannot fix all of the societal issues plaguing these schools.

It’s time for us to do the hard work of addressing the real issues that impact public education. It’s time for our politicians to stop posturing and engage in an honest and open dialogue on what is happening in schools. It’s time to stop blaming and start talking.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured