Opinion: Changes in ACT benefit privileged kids, but how about rest?

Allyson Gevertz is a longtime education advocate in DeKalb County who is now a school board member. She has also worked as a school psychologist for Gwinnett County.

In this piece, Gevertz discusses the recent decision by the ACT to allow students to retake individual sections of the ACT rather than taking the entire three-hour test over to try and raise their score. Each section -- English, math, reading, science and/or writing -- earns a scaled score between 1 and 36 that contributes to a composite score, also scaled to 36. So, a student who did well on every section, but math will be able to register to retake only math starting in September of 2020.

Gevertz cites equity concerns round this change in the ACT, as does Robert Schaeffer of FairTest. "Losers are kids from historically disadvantaged backgrounds whose scores will fall further behind because they will not know how to 'game' the new system and many school counselors/test supervisors who will have to spend more poorly paid time administering a confusing set of options," says Schaeffer.

By Allyson Gevertz

I thought the tide was shifting. In the wake of the college admissions cheating scandal, it seemed like America was finally acknowledging inequities long ignored. Transcripts of test-fixer Rick Singer's conversations with his wealthy clients showed that those parents felt entitled to "help" their children even through illegal means.

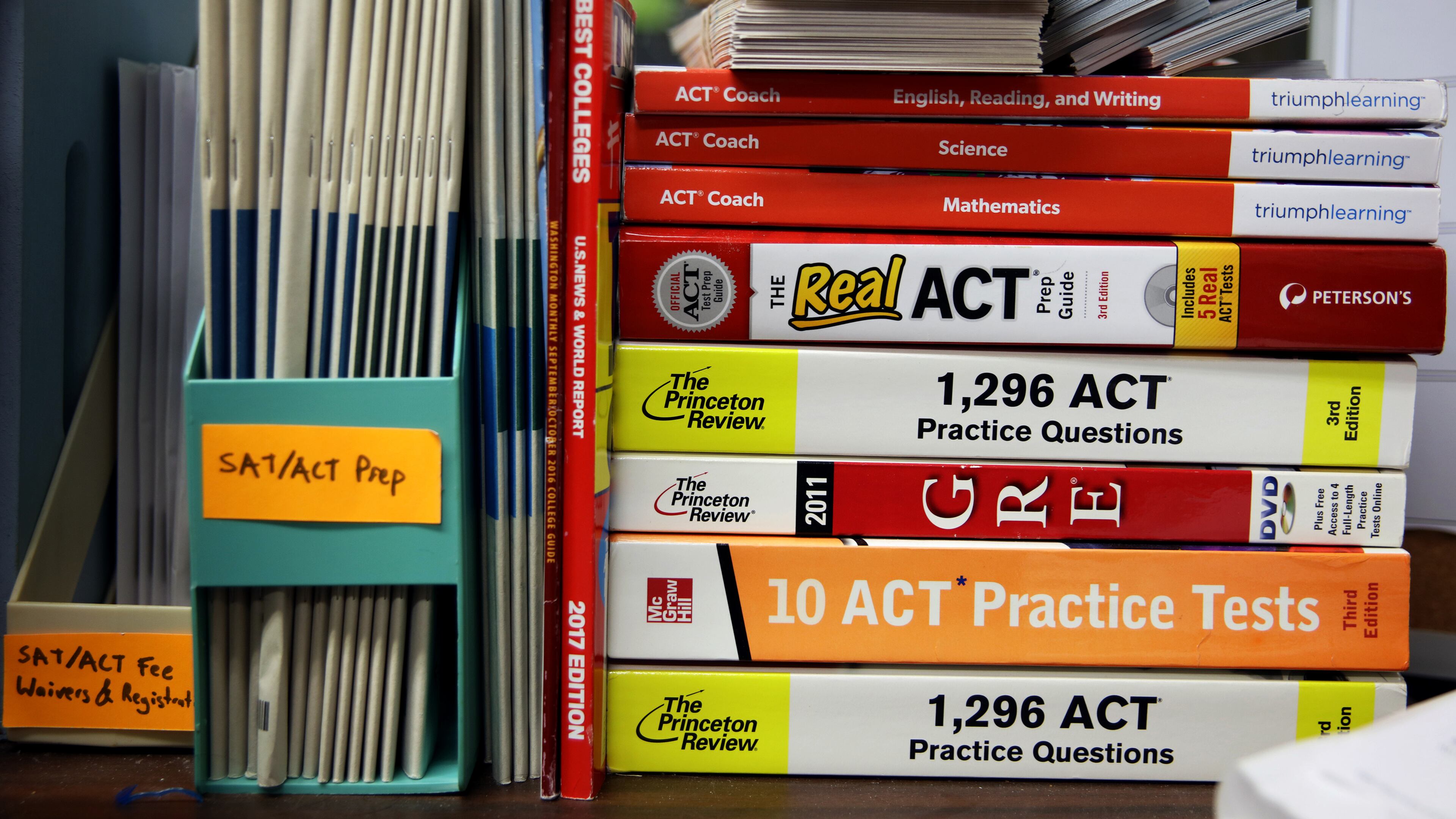

One parent verbalized the reason for using the “side door” to access elite colleges: “The bottom line is I want my guy to have every opportunity that hardworking qualified kids have.” The message was clear: privileges such as high-quality education, test prep tutoring, college admissions consultants, multiple standardized test administrations (and fees), and cultural expectations of higher education attendance were not enough. These students deserved an extra boost above the students who worked hard enough to test well despite obstacles such as attending “failing” schools, the inability to afford tutoring, lack of familiarity with collage entrance requirements, and having fewer opportunities to take a standardized test (due to the time, transportation, and monetary requirements).

Really?

Once this story broke, I believed Americans would demand fair assessments of students entering college. The practice of offering fee waivers and the College Board’s SAT “adversity index” showed some acknowledgment of equity issues, but I thought college entrance exam companies might finally engage in some soul searching and revamp their entire approach.

I was wrong.

Two weeks ago, the ACT announced that students will be able to retake specific sections of their test, starting next year. Upon hearing this news, my first thought was for my own child. He recently took the ACT for the first time. Overall, he was happy with his scores, but one section was lower than he had hoped. We debated whether he should retake the test, but in an effort to reduce the already-ridiculous amount of stress caused by admissions testing, we ultimately decided against it. Hearing about the ACT change coming next year caused us to rethink that decision. We have the resources to invest in tutoring, and my son is a motivated kid. He could target his low section and retake that section until he improves that score.

How nice to be privileged enough to consider intensely focusing on one section of the ACT.

My second thought was for the students of DeKalb County School District. If some students have the resources to intensely target one ACT subtest, shouldn’t all students have that chance? The DeKalb School District was committed to equity and access long before those became standard buzzwords in American eduspeak. As a school system with 70% of students receiving free and reduced-priced meals, our district is constantly searching for ways to ensure equity. This analysis occurs with everything from the age of elementary playground equipment to the allotment of reading specialists.

It also happens when the subject of college admissions testing arises. In fact, an agenda item for College Board AP exam test fees sparked discussion prior to the last Board of Education meeting. It’s a complicated issue. Some of our high-poverty schools consistently have low numbers of students passing AP exams paid for by the district. One question was whether the district should continue to pay the fees for AP exams or put the funding toward programs meant to increase the subject-matter competency of the students struggling in AP classes.

Once again, I found myself bemoaning the fact that these standardized tests (and the practice of teaching to those tests) commandeer so much for our time, attention, and resources. My guess is that, sometime soon, school districts will be devising strategies and finding resources to provide students access to retakes of specific subtests on the ACT.

Evidence suggests that school districts and colleges are rethinking the importance of standardized testing. Many colleges have adopted test-optional policies, while school districts are moving away from high-stakes testing, toward frequent, embedded assessment of student learning.

Where are the College Board and ACT in this movement? Did the college admissions scandal cause them to rethink their core objectives? Are they willing to risk their financial bottom line to meet the needs of all students, especially those without support, let alone a “side door”?

When I was in graduate school, I was taught that college admissions tests (which at the time, were generally taken once with no test prep) did a good job of predicting how a student would perform in college. That was when the majority of college-bound, test-taking students were white and had college-educated adults in their families. Times have changed dramatically, and now, test scores show an incomplete picture at best and a measurement of entitlement (and possibly fraud) at worst.

My message to ACT is this: please rethink your plan. Our students deserve better. Take a cue from school districts across the country and rethink the concept of assessment through the lens of equity.