Since abandoning the ambitious education programs of the late 1960s and early 1970s that reduced the black-white achievement gap, Linda Darling-Hammond said America stepped back from its commitment to equity.

“We had an era in which the discourse became money doesn’t make a difference. There is nothing you can do about it. Pull yourself up by the bootstraps. Then, high-stakes testing. You know -- let them eat tests instead of cake. That has been what we have been struggling with in the era since,” she said.

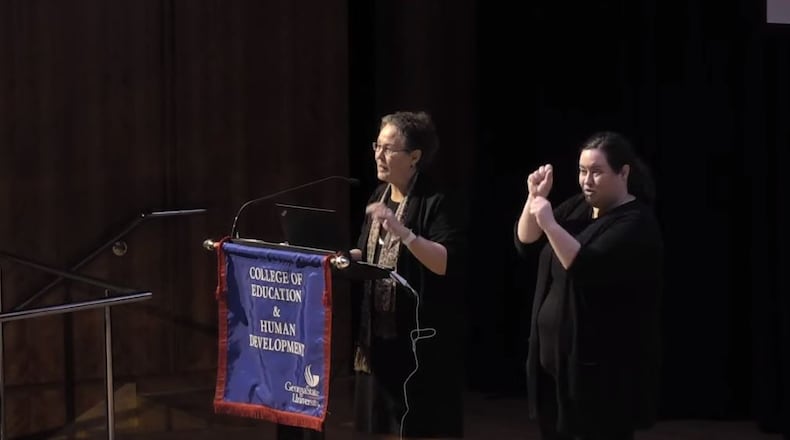

A leading voice in how to improve teaching and learning, Darling-Hammond is the Charles E. Ducommun Professor of Education Emeritus at the Stanford Graduate School of Education, founding president of the Learning Policy Institute, president of the California State Board of Education and author or editor of more than 25 books on education policy and practice. In 2008, she served as the leader of President Barack Obama's education policy transition team.

Last week, Darling-Hammond delivered the 31st annual Benjamin E. Mays Lecture at Georgia State University. Mays was a civil rights leader, president of Morehouse College, teacher and mentor to Martin Luther King, and the president of the Atlanta Board of Education who oversaw the desegregation of the city's schools.

Darling-Hammond blamed rising inequities in America’s classrooms on a collision between the rapid resegregation of schools and disparate funding policies that give poor schools less of everything.

Saying she once believed history moved in a form of liner progress, Darling-Hammond said, “But, in fact, we take two steps forward and then we get pushback and then we try to take two steps forward again.”

She cited the education gains the United States realized as a result of Great Society and anti-poverty reforms, saying now progress has slowed and, in the case of the achievement gap, reversed.

Pointing to Atlanta as an example, Darling-Hammond said, "There is no highly segregated city that does not have a huge achievement gap."

When America retreated from integrated schools, which Hammond said were producing gains for all children, it did so under the guise of returning to neighborhood schools. But the retreat led to profoundly unequal opportunities. Today, high poverty schools where 90% of students are poor are almost entirely populated by black and Latino students.

Segregation has been layered atop that poverty, leading to students having fewer educational resources, limited exposure to peers who can influence academic learning, and less experienced teachers, she said.

In U.S. schools where less than 10% of children live in poverty, America ranks No. 1 in the world in reading, she said. “Even in schools with 25% of kids living in poverty, we are No. 3 in the world in reading,” she said. “You cannot get to high achievement without investing in equity.”

Darling-Hammond addressed an array of topics and audience questions. Here are some of them.

What about charter schools? Darling-Hammond said charter schools were envisioned as hothouses for innovation that would function like traditional public schools, taking all student and serving them. While that is true for some charters, she said, "There has been a huge proliferation in for-profit charter schools, and many of them take state money, spend a third on kids and put two-thirds in somebody's pocket. And some charters take only the most advantaged kids."

Can school transformation occur? Yes, said Darling-Hammond, citing the academic ascent of the state of New Jersey, a majority minority state with 53% students of color and large immigrant populations.

Darling-Hammond was a student teacher in the struggling schools of Camden, N.J., where she recalled there were no books in the book room for students. Camden earned half of what wealthier districts like Princeton received in school funding, she said.

The unequal funding led to school financing lawsuit. said Darling-Hammond, adding, “Almost every state has a state flag, a state bird and a state school finance lawsuit”

In 1976, in response to demands for more funding, the New Jersey education commissioner declared that urban children, even after years of remediation, would never perform as well as their suburban counterparts, no matter the effort, said Darling-Hammond.

But, in 1998, the state equalized funding. It also provided two years of high-quality preschool, focused its curriculum and assessments on thinking skills, and invested in teachers.

Now, New Jersey ranks second in the nation in high school graduation, half a point behind Iowa, first in eighth grade writing, first in eighth grade math and second in eighth grade reading, said Darling-Hammond.

She also cited the improvements occurring in California. Last year, she became president of the state Board of Education. California, too, just equalized its funding

The state board studied outlier districts where low-income students outperformed expectations. It found “continuity of staff and leadership, a strong, stable educated workforce, districts that do not have the churn, superintendents who stay, as well as principals and teachers who stay. It turns out that the reform theory that disruption is the answer is not accurate, that continuity is deeply important,” said Darling-Hammond.

What works? Citing her recent study about traits of high schools serving poor students of color that produce high graduation and college attendance rates, Darling-Hammond said these schools were small and designed around a culture of caring.

“Many of them had looping where teachers stay with the same students for more than one year. That is common in many other countries. In the United States, our kids see about twice as many teachers as they do in many other countries. Those long-term, continuing relationships produce more achievement.

“Why? You get to know that child and you can use that knowledge for a longer period of time. Our schools are built for short-term relationships. We have a different teacher every year and a different teacher every 45 minutes starting in middle school. And that is when kids start falling through the cracks,” said Darling-Hammond.

What she would advise young teachers? "Find mentors and collaborators. Find the good in each of your students and call home with positive messages. Don't take it personally when kids act out. Ask what is going on with them. Love the children any way you can.

“Progress has been made and is being made every day in every school by educators who come and bring that love and that determination with them,” she said. “Get as much education as you can. Find the people who share your vision, your mission and your determination. As the saying goes, if you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured