DeVos contends giving students choice is solution. How about giving them stability?

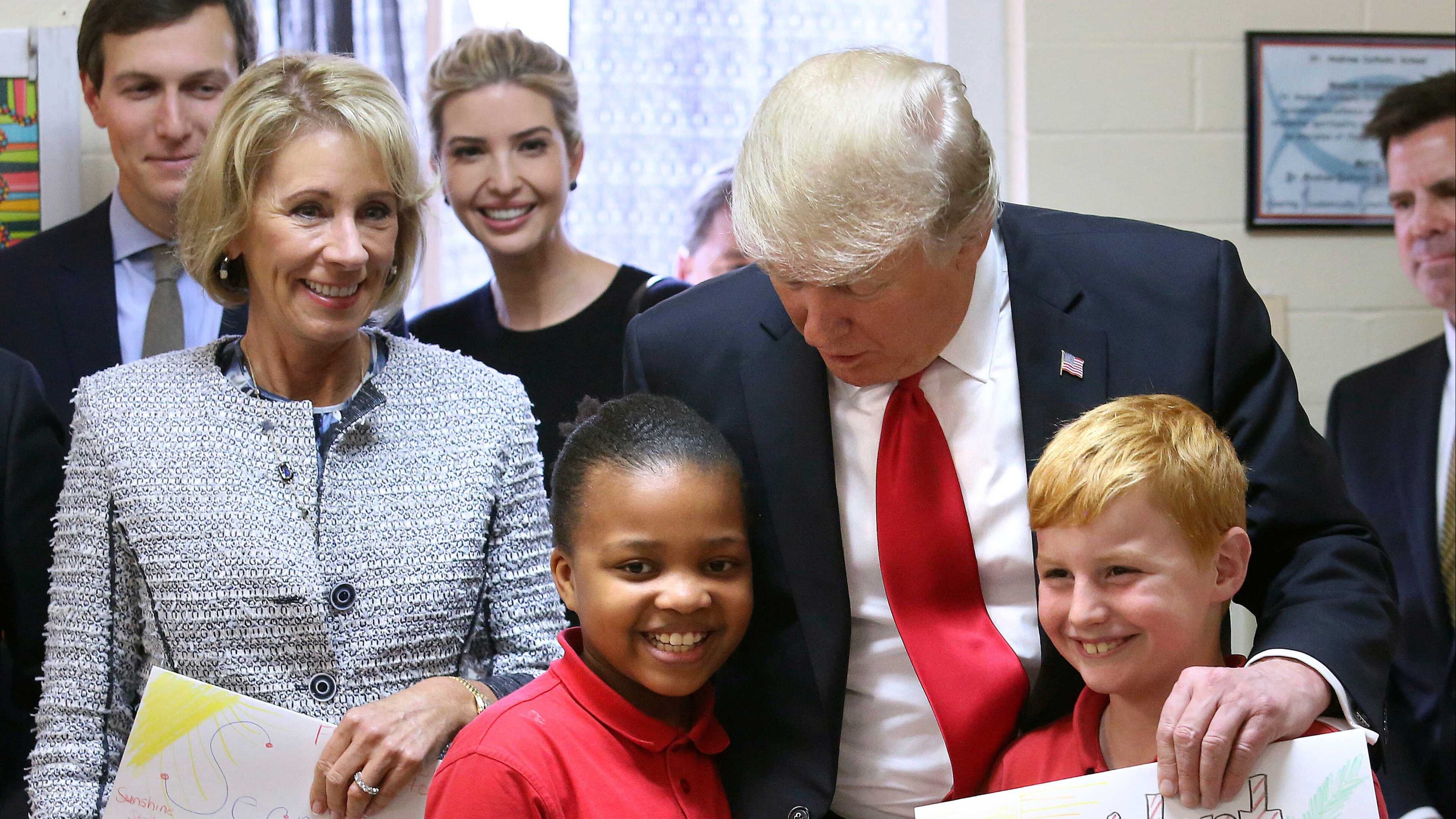

In her first eight weeks as U.S. secretary of education, Betsy DeVos has aggressively preached the gospel of school choice, commending vouchers, tax credit scholarships and charter schools at every turn.

Speaking shortly after a confirmation battle that required a tie-breaking vote by the vice president, DeVos told the Council of Great City Schools, “In too many cities and states, parents are still denied the simple, but critical choice of what school their child attends.” In a visit to a Catholic school in Florida, DeVos said, “Parents deserve the right to choose the education that is best for their child.”

She reiterated those positions today at the Brookings Institution, saying, "Just as the traditional taxi system revolted against ride sharing, so too does the education establishment feel threatened by the rise of school choice."

In touting choice, the secretary has cited the same success story -- Denisha Merriweather, a master’s degree student at the University of South Florida who attended President Donald Trump’s first address to a joint session of Congress and was acknowledged in his remarks. Failing third grade twice and about to be held back from middle school, the 25-year-old Merriweather was on a path to failure until Florida’s Tax Credit Scholarship Program enabled her to leave public school for a private Christian academy, according to Trump and DeVos.

But the president and secretary omit a few key biographical facts that contributed to Merriweather's academic turnaround.

In her account of her early childhood, Merriweather wrote, "Things at home were unstable. The time I spent with my biological mother was often in a Jacksonville hotel room. We moved more than five times over the next few years. With every move, I'd wind up in a different school. With every new school, I had to meet new teachers, administrators, and classmates."

But then Merriweather gained something that had been missing in her life, something research shows is critical to academic success – a consistent home life and role model.

Her life transformed when she moved in with her godmother at the end of elementary school. "She enrolled me at Esprit de Corps Center for Learning, a small, private school on the Northside of Jacksonville, using a Step Up for Students tax credit scholarship. Now my life had something it hadn’t had before: stability. I had my own room at home, which provided me a place of solace. I didn’t have to change schools anymore...she had a job at a Brooks Rehabilitation facility, made an honest wage, and set a good example for me."

Today, the House and Senate education committees listened to former Marietta High School principal Leigh Colburn talk about what she discovered when she asked hundreds of students unlikely to graduate what got them off track, where it wrong for them in school.

The teens didn't blame indifferent teachers or crowded classes. They listed far more personal barriers: Their parents' divorce. Homelessness. Family violence. Their father's death or incarceration. Their mother's drug addiction. The suicide of a friend. Their own addictions. Depression. A need to work two jobs. Four schools in four years.

And when Colburn asked what would keep them in school and focused, none mentioned the interventions emphasized in school improvement plans. They didn't point to increased academic opportunities and rigor or tutoring and summer classes. They cited grief counseling after their grandmother died. Help with rent when their family was evicted. Counseling for their mom. Therapy for themselves. A job for their dad. Stability.

Today, Colburn tries to provide those services at the Graduate Marietta Student Success Center she leads at Marietta High School. The 2-year-old program yokes community social services, academic assistance and behavioral support under a single roof in the high school. Students can obtain life coaching, professional etiquette training, yoga classes, interview skills, stress management techniques and wellness advice. There is a food pantry where kids can get a snack or a family the makings of dinner. There's a laundromat. Through a clothing closet, students can borrow, take or donate items. A range of community organizations, including faith-based groups, work with the Student Success Center.

The dynamic Colburn -- a possible candidate in my view for the state's newly created chief turnaround officer -- says, "The whole magic behind the center is to teach students to self advocate, to treat them with respect while they are doing so and, as timely as possible, to match them with the community partner that can provide the funding, the expertise and the resources to address their barrier."

It would be wonderful if simply changing schools could save at-risk students, as DeVos seems to believe. And that may happen for a few kids, but the obstacles to success undermining most students don't originate with the schools. And those barriers cannot be overcome by the schools alone.