Part 1

A saga begins

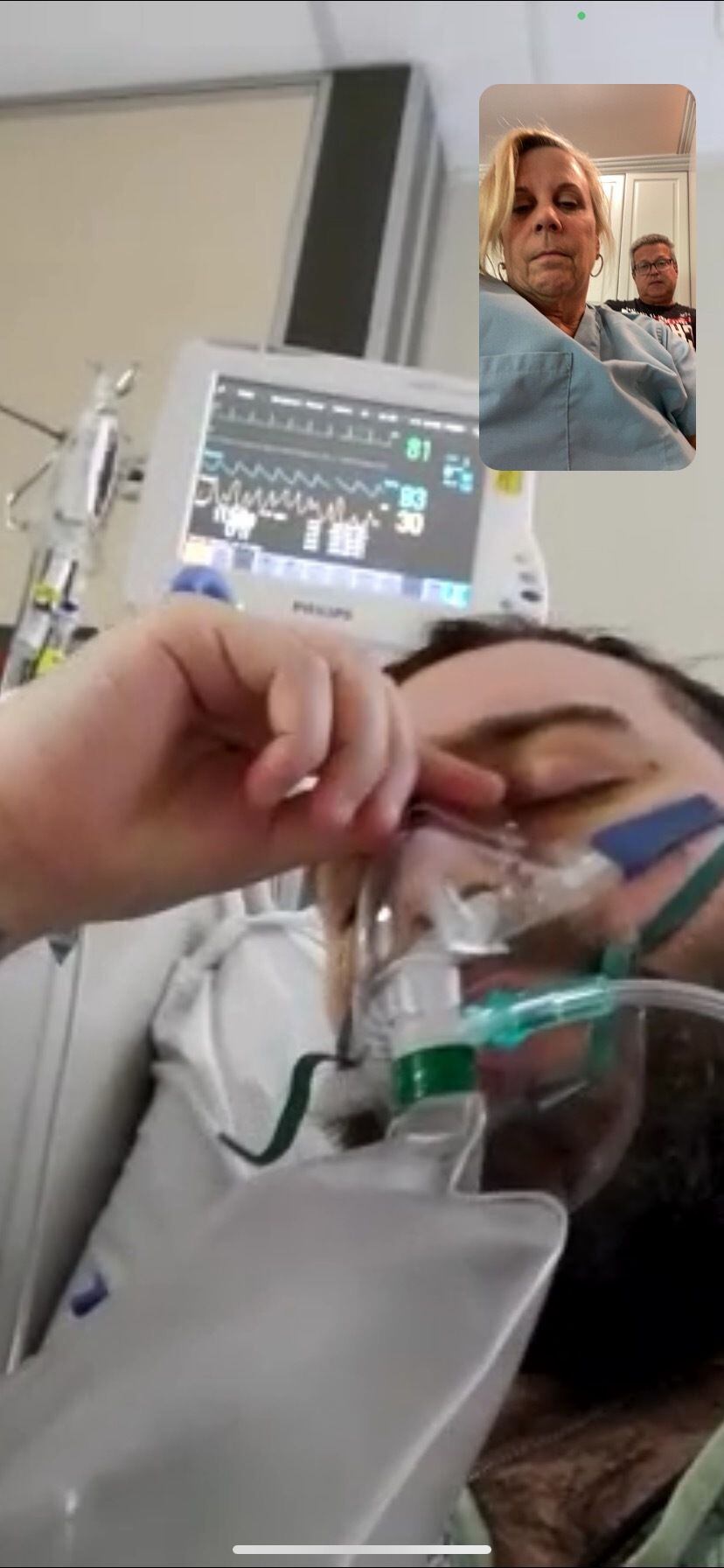

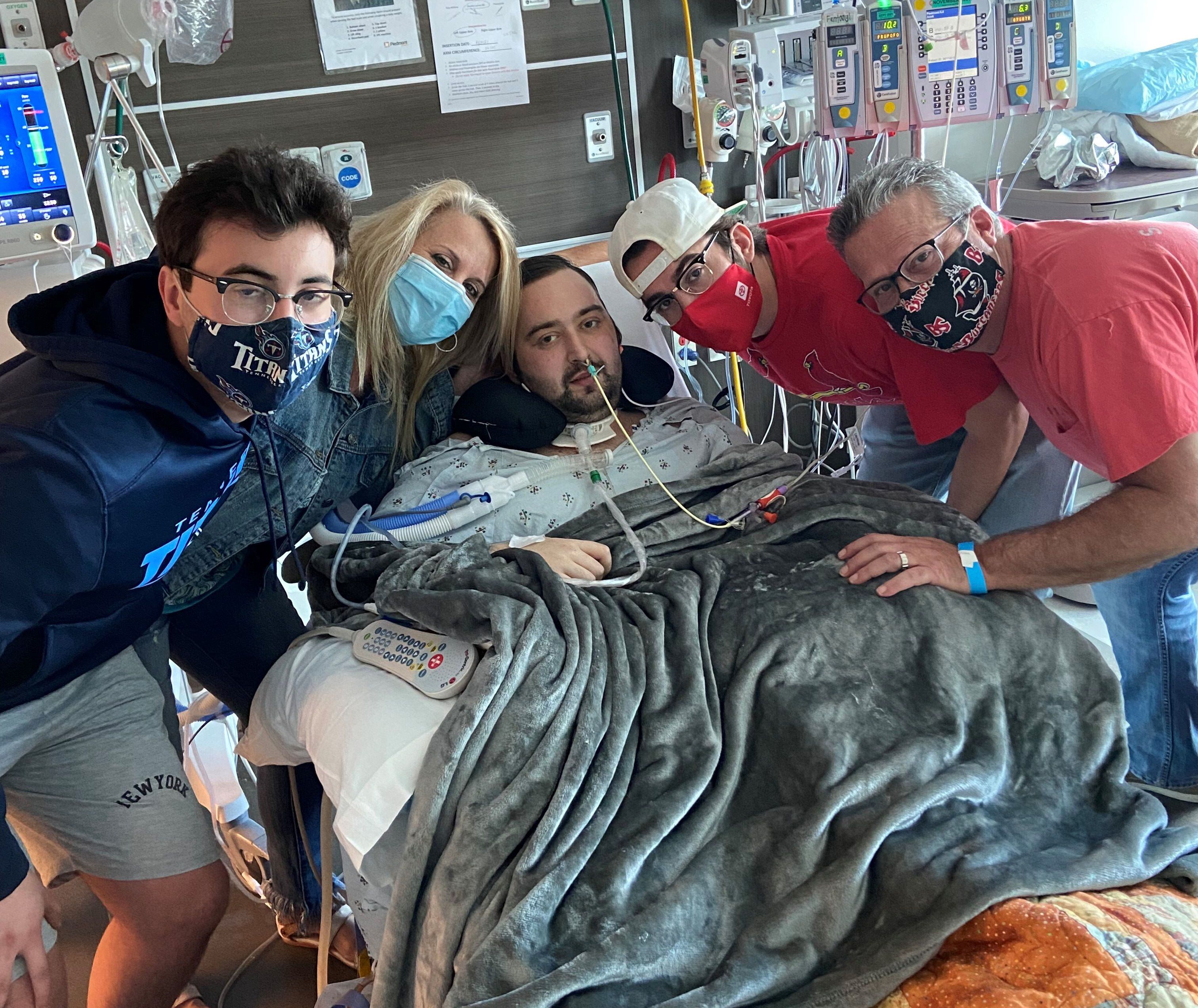

Cheryl Nuclo saw the photograph of her son and knew he was in serious trouble.

His normally expressive face was puffy and barely visible beneath a maze of medical tubing, his slate-blue eyes swollen shut. A ventilator hose was snaked through his mouth down to his trachea to keep oxygen flowing to his brain, heart and kidneys. A feeding tube in his nose carried nutrients to his body. A harness kept his head in place as an oscillating bed periodically flipped him to prevent fluid buildup in his lungs.

Again and again, she stared at the excruciating photo sent to her cellphone by hospital staff. Still, she had trouble taking it all in.

Just two weeks before, Blake Bargatze — a 24-year-old recent transplant to Florida — was walking, talking, going to the beach and discovering new restaurants. She was at home in Gwinnett County, juggling a hectic work schedule and busy personal life.

Now, here they were.

Him, in a medically induced coma, fighting a stubborn and bewildering coronavirus with every ounce of resistance that he, and the staff of St. Mary’s Medical Center in West Palm Beach, could muster.

Her, waiting in his apartment for updates from the hospital staff, barred from his bedside by still-in-place coronavirus restrictions.

It’s not surprising that Nuclo, who works as an anesthesia physician assistant for Emory Healthcare, was caught off guard by the ferocity of the virus’s attack on her son.

Through much of the pandemic, age and underlying conditions were the best indicators of whether a person would end up hospitalized with COVID-19. And those over 65 were hit hard.

But vaccines have changed the pandemic’s narrative.

Adults younger than 50 now make up the largest demographic of COVID-19 hospitalizations with the emergence of the ultra-aggressive delta variant, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s a trend that started in March. Younger people are much less likely to seek out the shots and tend to socialize more in crowds.

Most won’t get gravely ill. But for some, the virus’s attack becomes a fierce rampage.

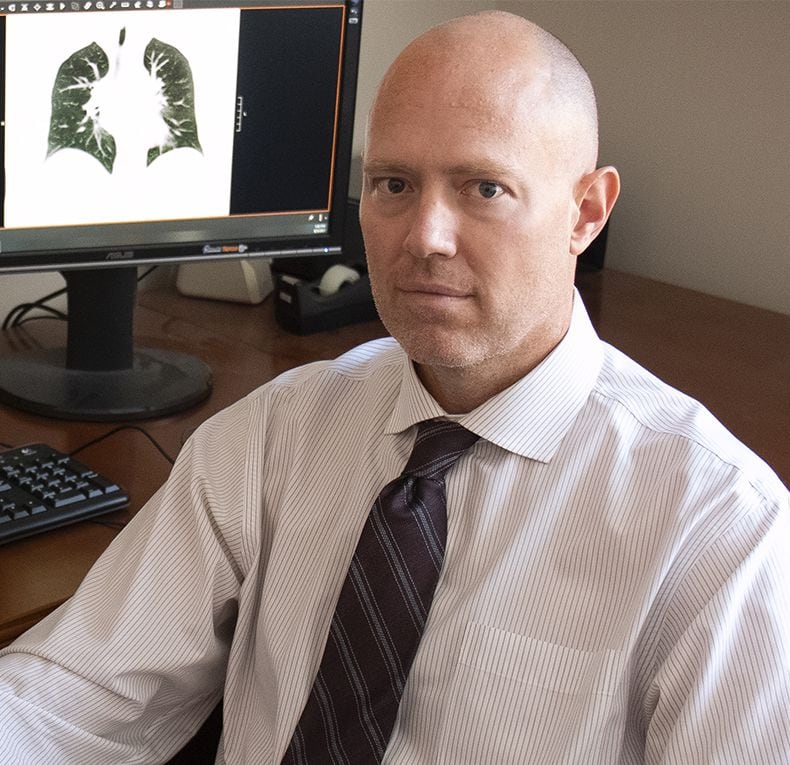

“There have been some with COVID I thought would do well and didn’t,” said Dr. Peter Barrett, medical director for the cardiac intensive care unit at Piedmont Atlanta Hospital. “I haven’t identified any one marker that says this person will recover or not recover. The honest answer is, we still just don’t know.”

For Blake Bargatze, it would turn into a fight for his life. He, his mother and his doctors agreed to share his story, to possibly prevent others from going through the same ordeal.

Taking off on his own

Bargatze, known for his loyalty to friends and playful personality, grew up in Gwinnett County and moved to Florida a couple of years ago.

He brought with him a passion for cryptocurrency, University of Tennessee football, Atlanta sports teams and hidden gem restaurants — nothing fancy, just good eats.

He started a job in sales with a business services company.

“When he moved to Florida, he made friends in a heartbeat, loved his job, liked the beach. It seemed like it was all coming together,” said his younger brother, 21-year-old Wesley Bargatze.

Nuclo was happy to see her oldest son taking off on his own. She knew they would remain close, no matter the distance. The two of them talked almost every day, even if it was just a quick check-in on his way to work. When he started working remotely because of the pandemic, he spent months at a time back in Georgia with his mother, stepfather and brothers.

For Christmas, they got him a telescope. He enjoyed the stillness of the beach at night and gazing at the stars.

Another affinity: old-school hip-hop.

Against his better judgment, he decided to go to an indoor concert March 27.

At the time, only 16% of Palm Beach County’s residents were fully vaccinated. Like most people under 40, Bargatze wasn’t yet eligible.

Bargatze was surprised by the size of the crowd at the concert. He had expected fewer than 100, but many more showed up. Though he felt uneasy, he went inside the tightly packed venue. Initially, he wore a mask, but thought it was too hard to breathe with it on, much less to sing. So he took it off.

Within a few days, Bargatze woke up feeling lousy. He had a cough, a bad one. A test confirmed he had COVID-19 so he made the dreaded phone call.

“Mom, you are going to be so mad,” he started.

“When I heard about the concert, I was like, really, Blake? But then I thought, we will get through this. You will be sick for a week or so, but we will get through this,” said Nuclo.

But with each passing day, Bargatze’s condition worsened: His cough was persistent. He was vomiting. His fever was high.

Then, on April 10, Bargatze told his mother he was dizzy, struggling to catch his breath. Nuclo instructed her son to go to the emergency room.

“I wasn’t surprised Blake got COVID,” she said. “I was surprised he got so sick from COVID.” Her younger son, Wes, had contracted the virus five months earlier. He, too, had a fever and fatigue, but his symptoms passed after five days of resting at home.

By the time Blake Bargatze went to the ER, he was gasping for air. He felt a burning sensation in his lungs and intense body aches.

Bargatze didn’t panic. After all, he didn’t know anyone his age who had become severely ill from COVID-19. He thought he would need just a few days in the hospital and he’d be back on his feet.

At the hospital, doctors found Bargatze’s blood oxygen level was dangerously low, and he was moved into the intensive care unit.

A normal oxygen level, as measured by a pulse oximeter, should range between 95% to 100%. Below 90% is considered low and very concerning. As levels drop into the low 80s, the danger of damage to vital organs rises. Bargatze’s was at 83%. As soon as he could, Bargatze made a video call to his mother.

She asked him to hold up his phone so she could see his stats on the machines monitoring him. With the oxygen therapy set at the highest flow, she knew her son’s oxygen saturation level should be at or near 100%.

When she saw his level, her heart sank. She knew what was coming next.

“You’re going to take a nap,” she told him, fighting back tears as she explained they would put him to sleep and put a tube down his throat to get his blood oxygen level up.

“I felt so horrible, but I didn’t want him to be scared,” Nuclo said.

The next day, her son was placed on a ventilator, and she got on a plane to Florida.

Going the extra mile

Bargatze had been intubated for close to two weeks when the nursing staff at the hospital in West Palm Beach reached out to Dr. Barrett at Piedmont Atlanta Hospital.

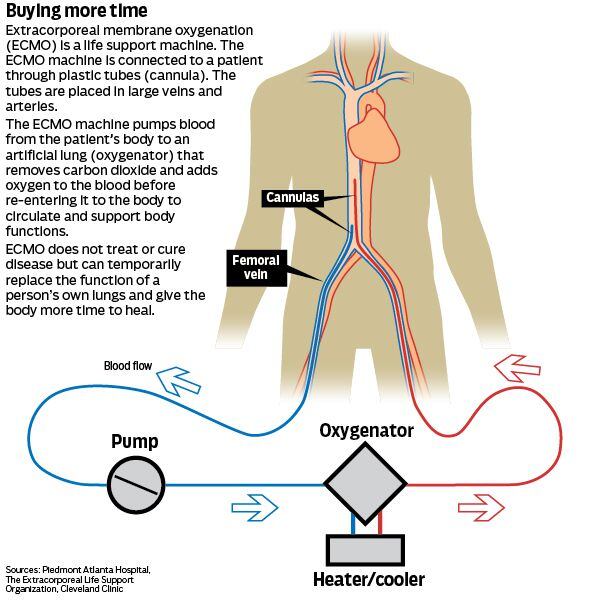

Bargatze wasn’t getting better and couldn’t hold on much longer without a therapy known as ECMO. That stands for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The machine takes on the work of pumping and oxygenating a patient’s blood outside of the body, giving the heart and lungs a chance to rest and, hopefully, heal. ECMO requires a specially trained staff that can provide constant monitoring and one-on-one nursing.

Only about 10% of hospitals have ECMO machines. Piedmont Atlanta has 12 machines but only enough staff for seven ECMO patients.

The nurses at St. Mary’s had contacted hospitals throughout Florida but couldn’t find an available machine. Out of desperation, they asked if Piedmont would take him.

Time was of the essence. In general, the sooner a patient is moved from a ventilator to an ECMO machine, the better the prognosis. In Bargatze’s case, the 13 days on the ventilator were “a bit of concern,” Barrett said.

Then he heard Bargatze’s age: 24. And he felt a tug in his heart.

“I thought about my twin children, who had just turned 26, and I thought I would want someone to go the extra mile if my child was sick. And I thought, if I would want someone to go the extra mile for my children, I need to do this for someone else’s child,” he said.

On the one hand, Barrett said, he was encouraged by Bargatze’s chances for recovery because he was young, healthy and, just days before falling ill, was working, enjoying time at the beach, living a “normal life.”

On the other hand, those factors gave Barrett pause.

An active, young man had “essentially face-planted, for lack of a better word,” the doctor said. Though Bargatze had a history of vaping, which Barrett says isn’t a good choice for anyone, it just didn’t explain how and why the coronavirus was ravaging his lungs. That made Barrett wonder if the treatment would be futile.

He started gathering information, talking to the doctors at St. Mary’s to see if Bargatze was, indeed, a good candidate for ECMO, not just someone he wanted to save.

The only chance for survival

ECMO involves sensitive timing. Start the intensive treatment too early and lesser therapies might not have been given a chance to work. Start it too late and damage might be too extensive for the body to overcome.

A total of 75 COVID-19 patients at Piedmont have been placed on ECMO for an average time of 21 to 30 days. About 65% survived. There was a good reason to try the aggressive treatment on Bargatze.

“With Blake’s case, his lungs were not working, but everything else was working,” said Barrett. “ECMO doesn’t cure or treat any disease. But, with this maximum means of support, the lungs can often get better if you can buy enough time.”

Nuclo saw it as her son’s only chance to survive. “I just felt like we had this window of time when he needed to start getting better, and we were missing out on it,” she said. “He was going to die.”

Piedmont decided to accept Bargatze.

His delicate transport would require an air ambulance, acquiring privileges at an out-of-state hospital, bringing along a portable ECMO machine for the plane ride and other complex logistics.

It’s not unusual to have patients transported to Piedmont for ECMO. Typically, they come from another hospital in Georgia or just beyond the state line.

Once Barrett decided Bargatze was a good candidate for ECMO, Piedmont’s staff went to work. “We were not going to stop until we got him,” the doctor said.

The transport was set for April 24. That morning and afternoon, thunderstorms, gusty winds and hail swept through the Southeast, creating very challenging flying conditions. There were reports of scattered tornadoes.

Barrett and one of the hospital’s ECMO specialists took off anyway in a small medically equipped plane from an airport in Lawrenceville. Their pilot masterfully steered around bad conditions, looking for clear pockets in the sky.

“I do always tell family members, whether on the ground or in the air, there’s a risk of death during transport,” Barrett said. “Things can happen, and, by the grace of God, they didn’t.”

But, though the trip from Atlanta to West Palm Beach and back was surprisingly smooth, the road ahead would not be. Bargatze, Nuclo and Barrett didn’t know it, but their odyssey had barely begun.

Part 2

A miracle needed — and fast

Cheryl Nuclo has spent nearly four decades in medicine, first as a respiratory therapist and then as a physician assistant. If there’s one truth she’s learned in all her time roaming hospital corridors, it’s this: Keeping up a patient’s spirits is crucial, especially when the person’s health is failing.

So she threw herself into the task of trying to create a cheerful atmosphere around her 24-year-old son, Blake Bargatze, who was clinging to life.

She taped dozens of perky get-well cards among the intravenous drips, the monitors and various other machines in his room in the Piedmont Atlanta intensive care unit. Against the window, she propped a poster emblazoned with sun rays and the words “You’ve got this.”

She prayed constantly. And day in and day out, she talked to her son, even when he wasn’t conscious.

We love you.

Keep it up.

We are going to continue fighting for you.

And when she could no longer keep up the front, she would quietly slip outside into the hallway and cry so hard that she would nearly hyperventilate.

“There was this fear of the unknown,” said Nuclo.

Most people who get COVID-19 manage to shake off the worst effects of the virus in a week or two. And, by far, most Americans who develop severe cases of the illness are older or have underlying conditions.

But, for reasons that doctors still don’t fully understand, Bargatze was one of the exceptions. Despite being young with no chronic conditions, he was so sick with COVID-19 that his doctors made the decision to turn to a last-resort treatment: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, therapy. An ECMO machine, an advanced form of life support, takes over the functions of the lungs, giving them a chance to heal.

With no machine available in Florida, where Bargatze was living at the time, he was put on a medical flight to Georgia, where he grew up.

But after weeks of the therapy, his prognosis remained grim.

“Taking care of patients with COVID-19 can be a mentally and physically draining process, and progress is usually seen in baby steps,” said Dr. Peter Barrett, medical director for the cardiac intensive care unit at Piedmont Atlanta Hospital. “You ask yourself, and people wonder, are we making a difference? Or are we just delaying the inevitable of someone passing away?”

No signs of improvement

Bargatze tested positive for COVID-19 in early April, before he was eligible for a vaccine. He, his mother and his doctors agreed to share his story to spare others a similar ordeal.

Since the spring, more and more coronavirus patients have been ages 18 to 49, and that group now makes up the largest share of the country’s COVID-19 hospital admissions: about 40%. That’s because the highly contagious delta variant is causing a massive surge in cases and, evidence suggests, more severe illness.

Vaccines are now available for all Americans age 12 and older, but younger people are much less likely than older adults to get COVID-19 shots. Making matters worse, people in their 20s and 30s tend to go out socializing in crowds more, experts say.

Bargatze started to feel ill just days after attending an indoor concert.

As spring gave way to summer, the virus’s assault on his lungs was overwhelming. The weeks in the hospital also were taking a toll.

There were encouraging days: when he could first wiggle his fingers and toes, when he could mouth the words “thank you” and “I love you.”

But when he wasn’t heavily sedated, the slightest movement caused sharp pain, and the chest tubes felt like knives cutting through his diseased lungs, said his mother, who wasn’t allowed in his room until he tested negative for COVID-19. “Even his feet hurt,” she said.

His skin was pale and yellow, and his lips had a bluish tint.

“I was determined to do everything I could to at least give Blake a chance,” said Barrett, who also oversees the ECMO program at Piedmont. But the therapy had not been the lifesaving answer the doctor had hoped for.

Though a course of ECMO usually lasts four or five days for patients suffering respiratory failure, doctors have learned COVID-19 patients can require weeks. Even so, if the lungs are going to recover, signs of healing should be seen within 30 days.

When Bargatze hit that milestone, Barrett huddled with Nuclo to give an update. Her son was showing no signs of improvement. The damage to his lungs was irreversible. And he couldn’t stay on ECMO forever.

In general, patients on ECMO either eventually heal and are discharged from the hospital, or they experience complications and die.

But Bargatze was in a rare category: Neither was happening.

Doctors came to a devastating conclusion: Bargatze’s only chance at survival was a double lung transplant.

From one ledge to another

Though Piedmont does liver, kidney and heart transplants, the hospital doesn’t perform lung transplants.

Barrett had plenty of experience helping critically ill patients get transplants at other hospitals around the country, but he also knew it wouldn’t be easy.

“We got off one ledge to get on a ledge on another road,” he said.

With so much still unknown about COVID-19, Barrett said, some transplant programs “rightfully and understandably, don’t want to touch it.”

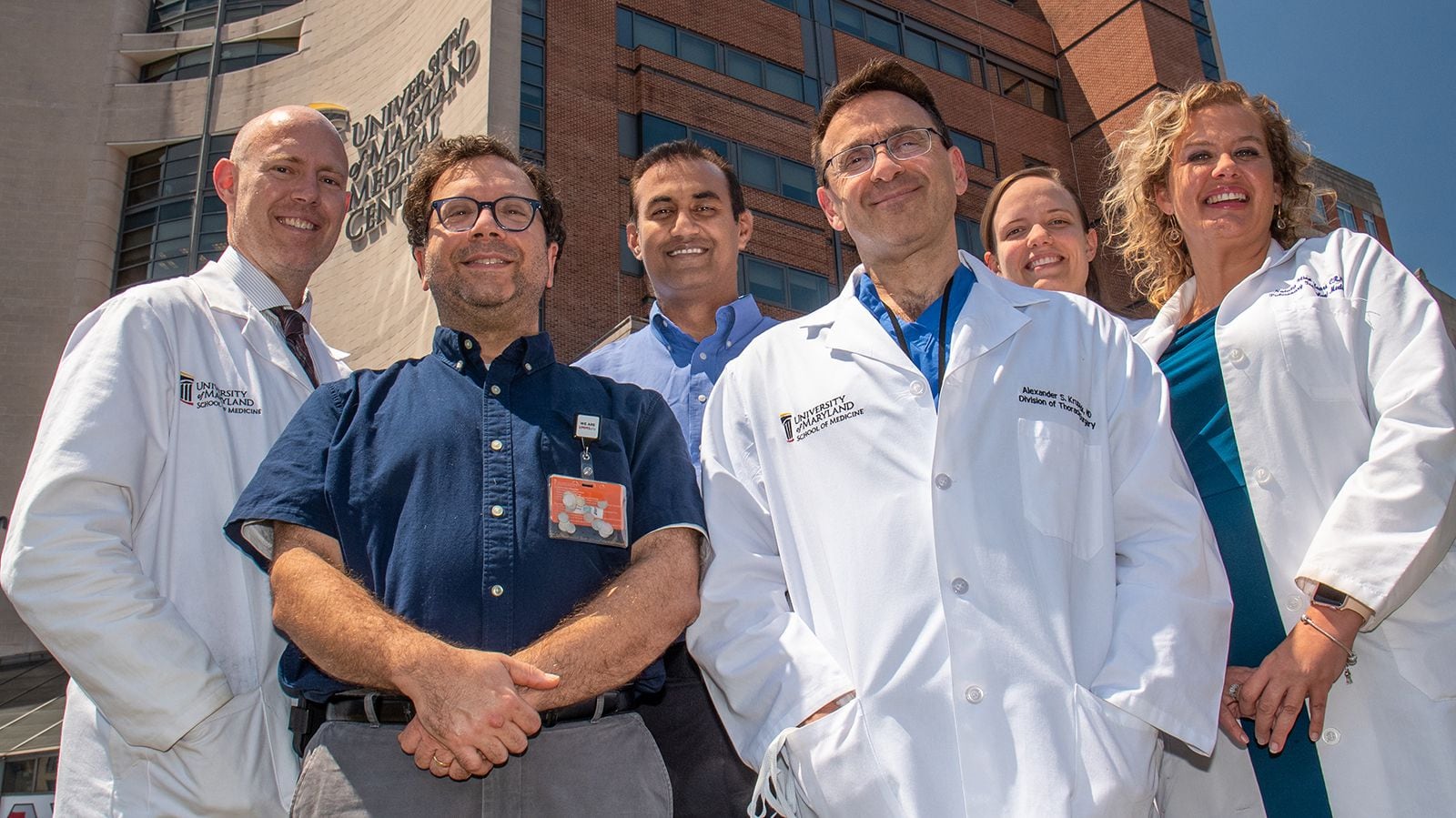

He reached out to eight hospitals around the country, including Vanderbilt, Duke, Houston Methodist, the University of Florida and the University of Maryland.

Early in the pandemic, doctors had started exploring the possibility of lung transplants to treat COVID-19 patients with catastrophic lung damage. It’s tricky because patients need to be clear of the virus. They also need to be strong enough to survive the operation and handle rehabilitation.

The first successful double lung transplant in the U.S. for a COVID-19 patient was in a woman in her 20s who was otherwise healthy. The operation took place in June 2020 at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

Since then, 180 more COVID-19 patients with lung damage have undergone transplants in the U.S., but they represent a small share of the roughly 5,000 lung transplants performed every year, according to United Network for Organ Sharing, or UNOS, the nonprofit group that manages the nation’s transplant system.

Many COVID-19 patients don’t get approved for reasons such as their age or other health conditions. Though Bargatze qualified based on those factors, there were other concerns. After spending more than six weeks in a hospital bed, he was physically weak, unable to stand or take breaths on his own, making him a less-than-ideal candidate.

Doctors used the term “jellyfish” to describe his condition. He was so feeble that he could barely lift his hands off the bed.

Dr. Robert Reed, medical director of the Lung Transplant Program at the University of Maryland Medical Center, was part of a team of doctors who consulted about Bargatze.

“Because this was a man in his early 20s, that caught our eye,” said Reed. “Twenty-something-year-olds are tough and have an ability to overcome a lot of problems that come their way.”

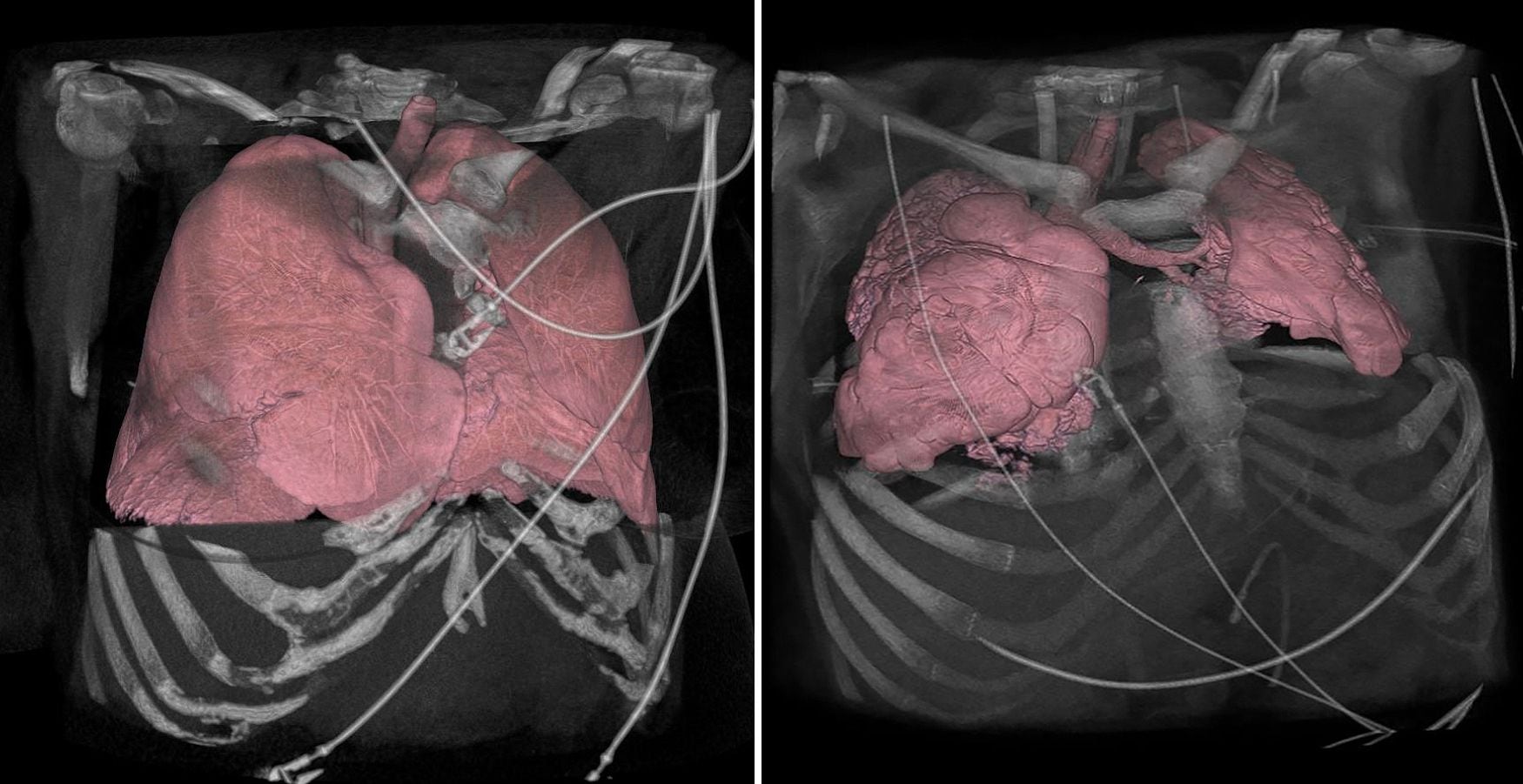

There was no question Bargatze’s lungs had been destroyed by COVID-19.

“They were horrible,” said Reed. “They didn’t even look like lungs at all. They looked like little pieces of liver.”

But the University of Maryland Medical Center prides itself on taking a scientifically informed holistic approach, one that takes into consideration not only patients’ conditions, but also their attitudes and support system, Reed said.

The transplant team felt that, with Bargatze’s youth and otherwise good health, he would be able to handle the challenging surgery.

'I want to live'

Nuclo had many hard conversations with her son. In his weakened state, he might not survive the surgery. If he did, he would need to take anti-rejection drugs for the rest of his life. Statistics said he still wouldn’t live a long life, maybe 10 additional years with the new lungs.

He listened intently and mouthed the words: “I don’t want to die. I want to live.”

“It needed to be his decision,” said Nuclo. “If my son didn’t want to fight, I would not have the fight in me because of the pain I saw in him over and over.”

Once Bargatze made it clear what he wanted, Nuclo went into action mode.

“That’s when I threw all of my efforts into making his wishes come true,” she said.

Bargatze also made another decision. In whatever time he had left, he wanted to encourage others his age to get the vaccine, to take the virus seriously. With another COVID-19 surge on the horizon, he and Nuclo granted several interviews to news outlets to talk about their journey.

In late June, Reed’s team at UMMC accepted Bargatze as a lung transplant patient.

Before heading to Maryland, Bargatze got a visit from a childhood friend. Garrett Woodall was stunned by the severity of Bargatze’s condition. It was hard for Woodall to wrap his head around the thought that someone his age was so desperately sick with COVID-19.

Woodall had planned to wait to get the vaccine.

But Bargatze mouthed to him the words, “Get it. Get it.”

Woodall said he knew what his friend was trying to tell him.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

Barrett accompanied Bargatze on the medical flight to Maryland. Saying goodbye, the doctor told his patient that he expected to see him walking through the doors of Piedmont Hospital one day soon to see all of the nurses who took care of him for more than two months.

“It’s going to happen, Blake,” he said.

But even though they had found a transplant program willing to give Bargatze a chance at life, they still needed a pair of lungs. And finding them presented perhaps the biggest challenge yet.

Bargatze’s blood type was rare: B negative. And while on ECMO, he had received several blood transfusions. The blood transfusions, though necessary, can lead to development of antibodies that can make it harder to find compatible organs.

After Bargatze’s antibodies were measured, the team at Maryland calculated what’s known as the panel reactive antibody. The PRA estimates the percentage of donors who would not be suitable. For Bargatze, the team estimated, fewer than 10% of donors would be a potential match.

Finding one was not an impossibility, but it was unlikely.

“It would be like lightning striking,” Reed told Nuclo on June 24.

Three days later, lightning struck.

Part 3

Overcoming the odds

Blake Bargatze was sick of the hospital beds, sick of the monitors, sick of the tubes, sick of the medicines, sick of his failing lungs and utterly sick of COVID-19.

He was desperate to resume life outside the walls of his intensive care room and ready to get on with any treatment that would let him do that.

But on that day, a doctor at the University of Maryland Medical Center had shared with the 24-year-old a heartbreaking calculation. Taking into consideration Bargatze’s blood type, his immune response to blood transfusions, how rarely usable lungs came along, he was probably looking at another two months or more in the hospital as he waited for a double lung transplant — time that he might not have.

For a young man who already had spent more than eight weeks in three hospitals, almost always on the verge of death, the words were unbearable.

They were still ringing in his ears that evening when his mother, Cheryl Nuclo, left the hospital to return to her nearby extended-stay hotel.

As she sat down in her room to unwind, she found that she, too, was deflated.

Then, just like that, everything changed.

As Nuclo was eating takeout, her cellphone rang. Dr. Robert Reed told her that he’d received notice of a possible organ donor match — “a miracle match,” as he described it.

The transplant team would still need to inspect the lungs, Reed said, but he was optimistic.

Nuclo couldn’t believe what she was hearing. She was deliriously happy, though she was also torn. Should she wait until doctors knew for sure that the lungs were a match before saying anything? Should she share the news with her son right then to give him the lift he so badly needed?

She was still debating what she would do as she grabbed her things and rushed back to her oldest child’s side.

The million-dollar question

Bargatze’s COVID-19 battle began in late March. He attended an indoor concert in South Florida, where he was living at the time and was not yet eligible for the vaccine.

He started to feel ill within a few days and tested positive for the virus. About a week later, he started to feel dizzy and struggled to breathe. His mother, who lives in Gwinnett County, where he grew up, pushed him to go to the emergency room at St. Mary’s Medical Center in West Palm Beach.

Doctors there found his blood oxygen level was dangerously low. Bargatze was placed on a ventilator, yet his condition only became more dire.

He needed to be hooked to a life-sustaining mechanical system called extracorporeal membrane oxygenation that could do the work of his lungs, so he was transported to Piedmont Atlanta Hospital. His lungs didn’t heal, though. Not only was he unable to breathe on his own, but he could also no longer walk and could barely lift his arms.

Dr. Peter Barrett, medical director for Piedmont Atlanta’s cardiac intensive care unit, determined in late May that only a double lung transplant could save his patient.

Barrett contacted eight transplant hospitals. Only the University of Maryland Medical Center accepted Bargatze as a lung transplant patient.

Though transplant centers follow strict criteria to determine whether to accept a patient for a lung transplant, Reed said his team in Maryland prides itself on taking a more nuanced assessment. The team had arranged a video call with Bargatze.

“We prefer to meet someone, get to know the person,” said Reed, medical director of the Lung Transplant Program. “We make decisions informed by science and data but do our best to integrate the information into our understanding of the patient to answer the fundamental and simple question: Will transplant likely help this person?”

Medical experts still don’t fully understand why the constantly adapting virus led to irreversible lung damage in Bargatze, while, in many of his peers, it causes only mild symptoms.

“It’s the million-dollar question,” said Reed. “I’ve seen some families where one person has it and nothing, and another person in the family is terribly sick. And I’ve seen other cases where, within a family, every family member is horribly ill.” The pandemic has been equally erratic. In the few first months after Bargatze was diagnosed with COVID-19, infections in the U.S. and Georgia dropped to lows not seen since the pandemic’s beginning. Now the numbers are soaring again, threatening to reach the highest level yet.

The supercontagious delta variant is casting such a wide net that those who once seemed impervious to serious illness from the virus — people 49 and younger — now make up nearly half of the coronavirus patients filling the nation’s hospital beds. These also are the people least likely to be vaccinated.

‘It’s going to happen’

By the time Nuclo arrived back at the medical center, the hospital staff had started early preparations for the surgery, which would go forward the next morning if the lungs got final approval. Nurses, doctors and technicians were filing in and out of Bargatze’s room. It was obvious something big was happening.

Nuclo held her son’s hand and looked directly into his slate blue eyes.

”Blake, we got the call,” she said. “They have some lungs they think are going to be a match for you.”

”Are you kidding me? Are you kidding me?” Bargatze asked.

She gave him all the warnings she had been given: It was still possible the lungs might not be a match. The lungs still needed to be inspected.

“I’m not worried,” said Bargatze, crying. “It’s going to happen.”

The next morning, on June 28, at about 7 a.m., as a team of nurses and doctors wheeled Bargatze to surgery, he broke down in tears again.

A nurse asked him if he was scared.

“No,” he said, tears streaming down his face. “I’m not scared. I’m just so happy.”

Bargatze entered the operating room as one of the nation’s youngest lung transplant patients due to organ damage from COVID-19.

The University of Maryland Medical Center has performed four lung transplants on COVID-19 patients. Reed said three survived and are doing well. One died of transplant-related complications not directly tied to COVID-19.

The surgeons who performed Bargatze’s surgery have discovered that the already-complex procedure has additional challenges with COVID-19 patients.

Though a typical lung transplant takes about six hours, operations on patients with COVID-19 lung damage can take about twice as long. COVID-19 patients have scar tissue in the chest that is actively inflamed, and they tend to bleed a lot. Bargatze required about 10 units of blood in the operating room compared with about 5 1/2 units of blood for a typical double lung transplant recipient.

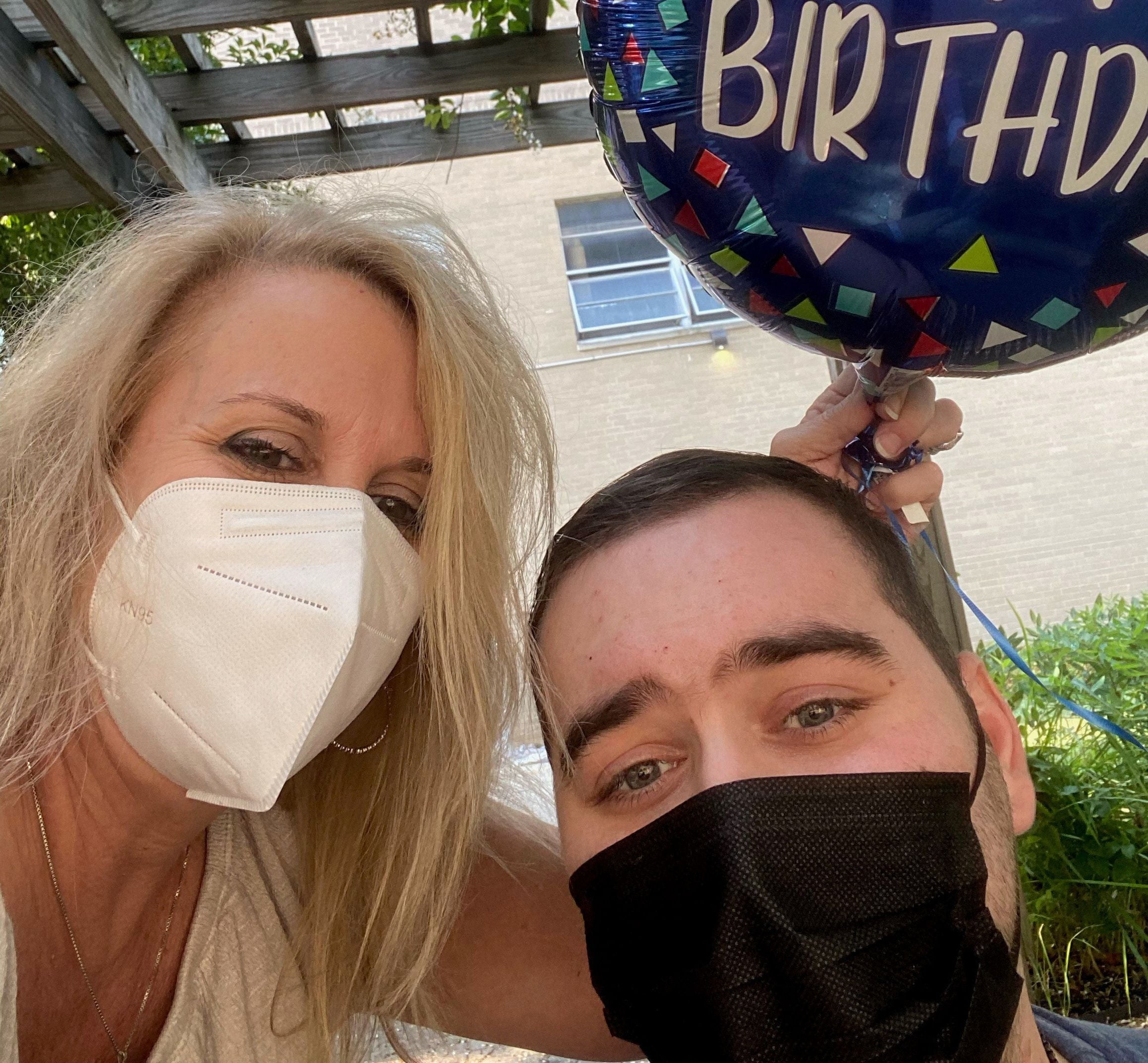

A birthday celebration with special meaning

During the nearly nine hours of surgery on her son, hospital staff gave Nuclo regular updates that things were going well. “I didn’t have fear,” Nuclo said. “I felt this overwhelming sense of gratitude. I felt so grateful for what everyone had done for him. People had gone out on a limb for him. And here was this organ donation — such a selfless action helping people.”

At about 3:30 p.m., a surgeon told Nuclo the surgery was over.

Right away, the signs were encouraging: Blood tests, chest X-rays and other assessments all indicated the new lungs were being accepted by Bargatze’s body and functioning well.

He was expected to spend about eight weeks in the intensive care unit, where he could be weaned off the ventilator. However, in late July, he celebrated a major milestone: He moved to the inpatient rehabilitation unit.

“The day after surgery, I couldn’t lift my hands off the bed,” said a smiling Bargatze in a recent video he took of himself standing. “A week ago, it took two people to get me on my feet, and, granted, I still have to use a walker, but I will be up and dancing sometime soon.”

On Aug. 9, Bargatze celebrated his 25th birthday. He completed a physical therapy session and spent a few minutes outside on a warm and humid Maryland day.

His mother brought him a vanilla cake, balloons and the one gift he asked for: a black onyx cross to replace the one lost somewhere along the way during his stays at three hospitals. In his long days and nights in hospital rooms, Bargatze’s faith in God helped sustain him.

“My birthday was a very special day because I was alive for it, and the biggest gift was a new pair of lungs,” he said. Friends, family and nurses from the University of Maryland, as well as Piedmont Atlanta and St. Mary’s hospitals, called and sent birthday wishes.

He has impressed the medical staff with his can-do attitude as he continues to work on his recovery.

Every day, between taking more than three dozen pills, he works with therapists to train his body to walk again and climb steps again and perform all the functions it did effortlessly just months ago.

At night, he connects with family and friends by text message. He’s granted several media interviews via video calls so that he can encourage others to get vaccinated.

Bargatze, who was vaccinated at the hospital in Maryland, said he knows many young adults don’t feel a sense of urgency; he was one of those young people.

“Originally, I was skeptical of the vaccine,” he said, his voice thin and raspy. “But it is very important, and I don’t want people to make the same mistake I made. Too many people are losing their lives to this virus, and there is something that can help.”

In his interviews, he also stresses the importance of signing up to be an organ donor. And he discourages vaping, a habit he had before his illness. Though Dr. Barrett said vaping doesn’t explain why Bargatze got so sick, he also said it certainly didn’t help his patient.

In such polarized times, reactions to Bargatze’s messages have been mixed. Many commenters on social media have said his story changed their minds about getting vaccinated. But some have been harsh: They assume he’s an anti-vaxxer, say he deserved to get sick or insist his case is a hoax.

Heroic efforts helped in fight

In the rehab center, Bargatze is learning a complicated, new lifelong medication plan to prevent organ rejection, which is a constant threat. Organ transplant recipients, who have compromised immune systems, always need to be careful to avoid germs. And Bargatze will need to be even more cautious during a pandemic with an evolving virus.

Only about half of the patients who receive lung transplants are still alive after five years, though there are cases when people have lived 10 years or more. The longest surviving lung transplant recipient lived 32 years after the operation.

“With Blake so young, I would guess he is likely to do quite well,” said Reed.

From Piedmont Atlanta, Barrett stays in touch with Bargatze’s mother so he can follow his former patient’s progress.

“I saw that fight, drive and determination in Blake,” said Barrett. “You have to want it. You can’t sit there and be, like, ‘Why me?’ This was a big operation, and you have to have an inner drive to get through it.”

Bargatze recognizes how valuable it is to have a devoted mom. She left the rest of their family — his brothers and stepdad — in Gwinnett County and took time away from her job as an anesthesia physician assistant to fight for him and be his voice when he couldn’t speak for himself. She, too, has moved to Maryland to be with him while he’s recovering. That’s expected to take at least six months.

The two of them have no idea what kind of world he’ll reenter. When Bargatze contracted the virus back in March, it was rare to see a person his age become so ill from it. But in the five months since, the faces in COVID-19 hospital wards have been getting younger.

He and his family credit his survival to the heroic efforts of three teams that are still fighting, daily, the menace of COVID-19: staff at St. Mary’s, who found Bargatze an ECMO machine in Georgia when one wasn’t available in Florida; those at Piedmont Atlanta Hospital, who went to get him in Florida, watched over him for 50 days on ECMO and found a transplant center willing to take him; and the team at the University of Maryland Medical Center, who saw him through his transplant surgery and will preside over his recovery.

But Dr. Barrett said he believes something even greater than dedicated health care workers and an extraordinary advocate in his mother enabled Bargatze to survive.

“What happened was a miracle,” Barrett said. “It was providence that he was given a second chance.”

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution first learned about Blake Bargatze's struggle to survive COVID-19 when a family friend contacted staff writer Helena Oliviero. Bargatze's family wanted to share his harrowing story, hoping that it will inspire more people to get vaccinated. Over several weeks, Oliviero interviewed Bargatze, who grew up in Gwinnett County, and his mother, Cheryl Nuclo, numerous times. Oliviero also interviewed Bargatze's team of doctors in Atlanta and Maryland. With his permission, they shared detailed medical information about Bargatze and the difficult road he faced.

Read further: How journalist Helena Oliviero presses on.

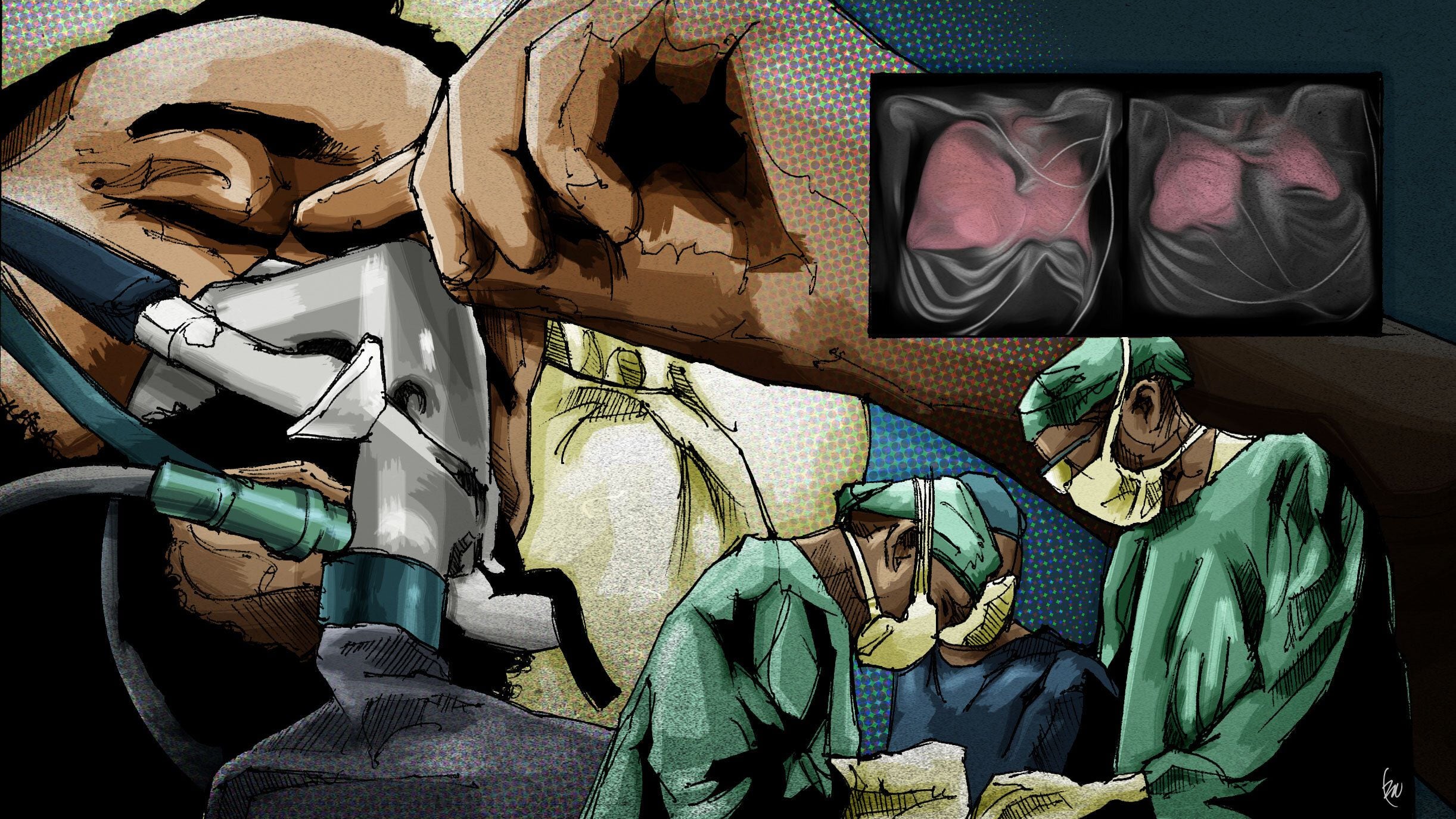

Staff illustrator Ric Watkins created illustrations for this article.

About the Reporter

Helena Oliviero is a longtime staff writer at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. She first started reporting about COVID-19 in December 2019 when the first cluster of coronavirus cases was reported in Wuhan, China. She’s been writing exclusively about the toll of the virus since a pandemic was declared in March 2020. She works to put a human face on statistics to help deepen our understanding of what’s happening.

About the Editor

Colleen McMillar joined the staff of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2006. She works with reporters to help them develop story ideas and produce engaging reads on a range of topics, including public health, gender issues, civil rights and the economy.