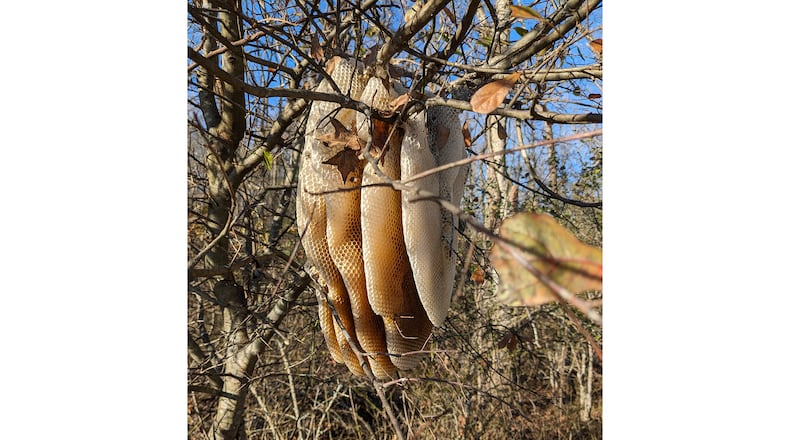

Q: Have you ever heard of an exposed honeybee hive? Is it common around here? Tim Thompson, Bartow County

A: The phenomenon of seeing the wax from an outdoor bee nest (not beehive) is not unknown, but it is certainly unusual. It is what’s left after a swarm of bees, led by a queen, can’t find a sheltered space in which to set up permanent housekeeping. Instead, the queen and her retinue alight on a limb and signal that this is the spot. Some of the workers begin collecting propolis, a strong material made from tree resin, beeswax and honey. It is what holds the nest in place and forms the structure of the nest. In the days that follow, the workers divide themselves into foragers and housekeepers. The housekeepers begin constructing the hexagonal cells for which bees are known. Forager bees get busy finding nearby sources of nectar and pollen to put in the upper cells of the nest. The queen is moved to the lower cells and she begins laying eggs. When foragers return, housekeepers take their load, mix it with bee enzymes and start drying it, fanning with their wings to evaporate water. Things progress nicely during the summer, and the wax structure of the nest grows larger as the queen lays eggs. Replacements emerge and go about the business of building the nest and making honey to fill the cells. Then cooler weather arrives. The queen leaves to spend winter in a protected place. As winter approaches, the workers gather in the center of the nest, using their body heat to keep warm. They bring in some of the larvae in order to keep them warm too. But it gets too cold to survive; the last workers and larvae die and fall from the nest. And you come walking along and see the nest ... and the rest of the story is in your hands.

Credit: Tim Thompson

Credit: Tim Thompson

Q: When should I put out a barred owl nesting box I made? Now? Wait a few more weeks? Mark Petro, email

A: Better get it done now. Owl love is in the air and the breeding season begins in January. I hope you have a tall ladder. The most attractive nests are located 20-50 feet high. A good site would be near water and low brush where rodents might hide. The female lays two to four eggs that she incubates for 28-33 days. The male feeds the incubating female. The young fledge around 42 days after hatching. For folks inspired by your mission but behind on building an owl nesting box, Audubon magazine has a great article about screech owls and their nesting needs at bit.ly/GAscreech. These diminutive birds love the suburbs, where spacious lawns and open spaces are good places to hunt and backyard bird feeders offer up small-feathered prey. Their nesting season begins in February, still enough time to flex somebody’s carpenter skills.

Email Walter at georgiagardener@yahoo.com. Listen to his occasional garden comments on “Green and Growing with Ashley Frasca” Saturday mornings on 95.5 WSB. Visit his website, www.walterreeves.com, or join his Facebook page at bit.ly/georgiagardener for his latest tips.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured