A rare disease exhausted him. A drug gives him energy to fight for others.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated with a news development.

MONROE — He had almost died as an infant, his little heart failing from an unknown condition, and now, at age 36, he was living with the same disease. Now he knew the name: Barth syndrome. His body malfunctioning at the cellular level. A death sentence for so many others. It was a Friday morning in September at the suburban house about 50 miles east of Atlanta where Walker Burger rented a room. He went to the refrigerator and took out a small white box. He reached in and pulled out a small glass bottle of clear liquid.

This story is about that clear liquid, what it means for Walker and others who depend on it, and what could happen if the liquid runs dry. At least one mother says the drug saved her son’s life.

On that morning, it all hung in the balance, at the mercy and discretion of certain government officials, who were expected to decide before the end of this month.

If the answer was no — if the investigational drug called elamipretide did not win approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration — Walker had no trouble imagining how his life could change. All he had to do was remember his childhood, or look at the old pictures his mother kept.

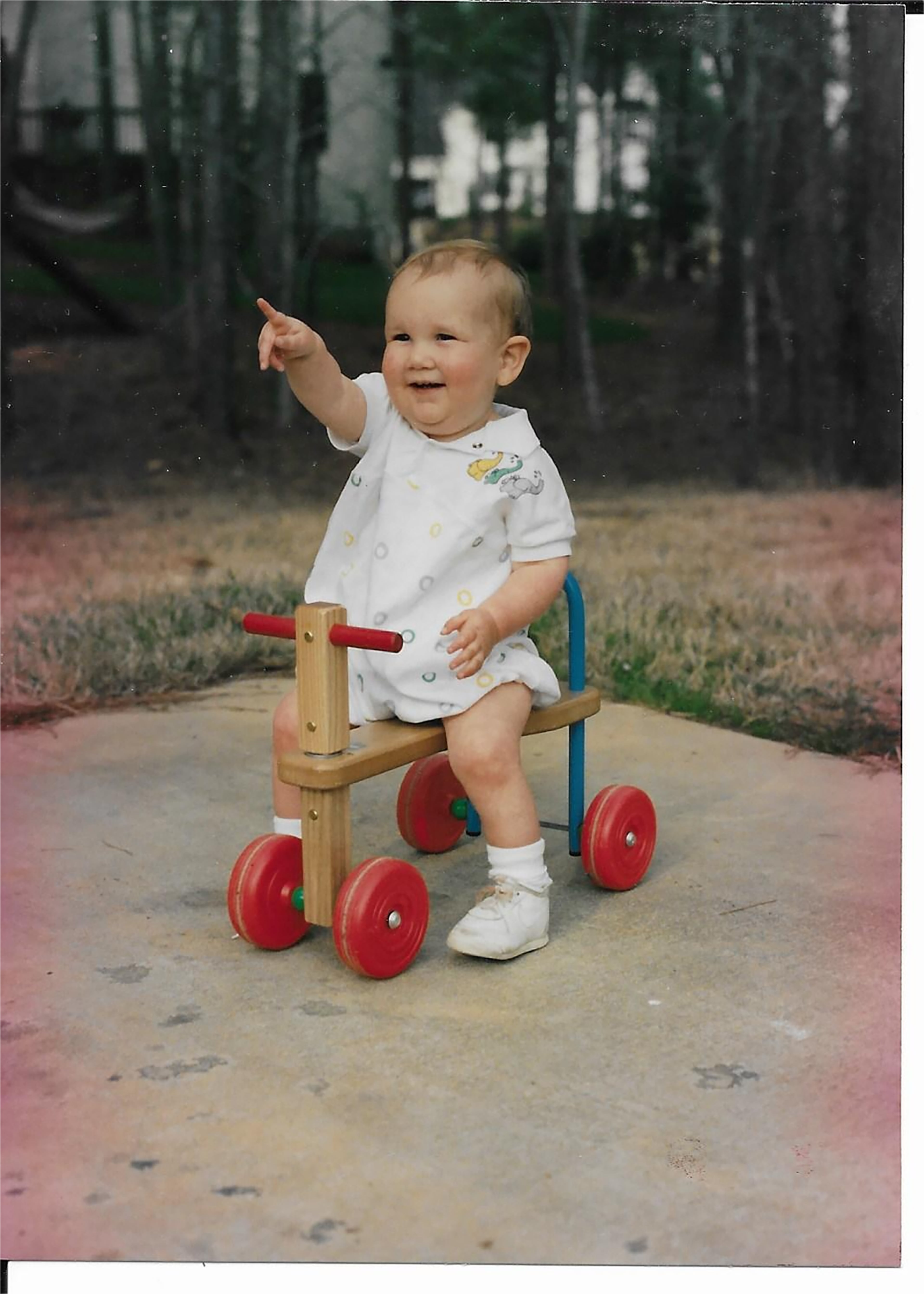

Here he is on a wooden scooter with red wheels, pointing at something outside the frame. His mother, Sally, wrote a caption: “Too weak to walk, Walker used this scooter to get around. He was almost 2 years old before he walked. After he walked, he still preferred the scooter.”

Here he is at age 4, baseball glove on his left hand, waving at the camera. He’s at a church softball game. One runner appears to be rounding second, another rounding third. They are obviously running. Walker loved baseball, but he never ran. He could barely walk.

If you have never known someone with Barth syndrome, you may not comprehend what it does to the muscles. There are people who struggle to open a bag of chips. Or carry a gallon of milk. There are adult men 6 feet tall who weigh less than 100 pounds.

Walker tried to play T-ball. He was “the worst player on the team,” he would later say. His older sister remembered him trying to go from first to second and getting passed by a teammate.

Minor exertions left him exhausted. When the family took a vacation to San Francisco, his father had to ask both his older and younger sisters to slow down, because Walker couldn’t keep up. Here’s one more picture of Walker as a child. He is lying on the floor, fast asleep.

Walker lived his entire childhood this way, staggering under the weight of unexplained fatigue. He could be so grouchy that his sisters called him Oscar the Grouch. He finally got the diagnosis at age 19. Like most rare diseases, Barth syndrome had no FDA-approved treatment.

Walker shuffled through his 20s, conserving his precious energy, sometimes going to bed right after dinner, and one day he heard that doctors were seeking patients for a clinical trial of an experimental drug. Walker signed up.

Eight years later, on a Friday morning in early September, he draws the clear liquid from the vial into a syringe. He wraps his fingers around the syringe, taking some time to warm the liquid so it won’t be too cold going in. He sits down in a chair and prepares the skin of his upper right thigh with an alcohol swab. And then, as he has done for more than 2,600 consecutive days, he injects himself with elamipretide.

The injections used to hurt, but now they just feel a little uncomfortable. It takes about 10 seconds to empty the syringe.

Walker is feeling reflective, sitting at the table, thinking about the journey that has led him here. He says the drug has not just taken away his chronic fatigue and made it easier to do his job as a government loan specialist and made it possible to work out at Planet Fitness. It has helped connect him with a new group of people he calls his family. And it has given him the strength to fight for those people — to fight for the lives of sick children — in an effort that has grown to include more than a dozen federal lawmakers from both major parties in Georgia.

“You know,” he says, voice breaking with emotion, “is this my life’s mission? Is this why, you know, I was — I was put on this earth?”

Barth syndrome affects fewer than 150 people in the United States. But Walker’s mission extends far beyond that population.

Elamipretide has shown promise in treating other mitochondrial disorders. And rare diseases, combined, affect almost 30 million Americans. Most have no FDA-approved treatment. Advocates have been closely watching elamipretide’s winding regulatory path.

“If a drug that is this good can’t get across the finish line,” says Shelley Bowen of the Barth Syndrome Foundation, “there is no hope for people with rare and ultrarare diseases in this country.”

For Bowen brothers, the drug arrived too late

There was once another little boy. His name was Evan, and he lived in Tampa, Florida. On his fourth birthday, when it was time for birthday cake, his friends climbed into their chairs. Evan tried to get into his chair. He kept trying. His mother offered to help him. He wanted to do it himself. But he did not have the strength. Finally he laid his head down and cried.

One morning his mother went to the grocery store. She came home to find Evan near the door, lying on the floor.

“He wanted to go with Mommy,” Shelley Bowen would later say, “but he just wasn’t fast enough to get to me to let me know.”

Evan never had another birthday party. A few months later he suffered a massive stroke. No one had a name for what was wrong with him, but his younger brother, Michael, had it too. After Evan died, Michael went into heart failure. His parents found out about a doctor in the Netherlands, Peter Barth, who was studying the same nameless condition that Evan and Michael appeared to have — a genetic condition whose symptoms included heart trouble and muscle weakness. Bowen took Michael to Amsterdam to see Dr. Barth.

“He said, ‘There are others, and you should find them, and if you find each other, you can help each other.’”

She did. Bowen co-founded the Barth Syndrome Foundation in 2000. They were beginning to understand the condition, but they still had no treatment. When Michael was in 10th grade, he was assigned to write an essay about fear.

“From the moment we take our first breath cells begin to die,” he wrote. “I have a rare disorder called Barth syndrome. I refuse to let the term life-threatening define me. Life itself is life-threatening.”

In his early 20s he looked out the window of his hospital room, watching the helicopters land, wondering if any of the patients inside might have the heart that could save his life. He died waiting for a transplant, two days after his 23rd birthday.

In a recent telephone interview, his mother was asked about elamipretide. Does she believe it could have saved her sons’ lives?

“I do,” she said.

Michael died in 2009. By 2012, a company in the Boston area reported promising results in an early clinical trial for a compound that could treat dysfunction in the mitochondria, where cells produce energy.

Five years later, as Stealth BioTherapeutics moved toward regulatory approval for elamipretide, Walker Burger enrolled in a trial and learned to jab himself with the syringe. The pain was excruciating. Those early injections took as long as five minutes. It was August 2017. By October, when his younger sister got married, his parents noticed a difference. He was happier, more energetic. People came up to his mother to ask not what was wrong with Walker, but what was right.

“Who are you,” his father, Lewis, recalls wondering, “and what have you done with my son?”

Walker’s big speech

On Oct. 10, 2024, at FDA headquarters in Silver Spring, Maryland, a man walked to a lectern and stood there, terrified. He wore thick-framed glasses. Dark wisps of hair fell sparsely across the top of his head. He was Speaker No. 1 at the public hearing, and he had four minutes.

“My name is Walker Burger, and my travel has been supported by the Barth Syndrome Foundation,” he said, looking at the advisory committee that had gathered to consider the merits of elamipretide. “… For 27 years, Barth syndrome controlled everything I did. But now I am living the life I could only dream about before.”

Walker knew it was the most important speech of his life. He had revised it, and revised it again. It felt as if lives might depend on how well he spoke.

“Growing up, physical activities had to be modified,” he said. “Something as simple as walking was a challenge for me. I was driven around summer camp to save my limited energy, as I couldn’t even walk a quarter of a mile without stopping.”

He waved his right hand to emphasize “quarter of a mile,” and moved on to a story about the start of the clinical trial.

“And on my way to the study site, I was running late to catch a flight,” he said. “I needed to run to the gate, but my legs just simply wouldn’t let me. I arrived as they were closing the gate, with tears in my eyes, full of disappointment and frustration.”

He described the dramatic change that came over him once he began taking elamipretide, the stunning improvements in his physical ability.

“In summary,” he said, “if someone were to ask me today if I have the symptoms of Barth syndrome, I would say, ‘No, I had the symptoms of Barth syndrome.’ Thank you.”

Walker stepped away from the lectern, grateful to be finished, and other speakers took their turns. Fourteen of them, including doctors, all speaking in favor of elamipretide. Amy Goldstein, an attending physician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, described the case of a baby so sick he needed machines to remove his blood, oxygenate it and then return it to his body. She put him on elamipretide and he recovered.

“So this was proof to me that this medication works,” she said, “and we hope that you think so too.”

Bowen told stories about her two lost sons. An Arizona woman named Jamie Dubuque told of her son Declan’s near-death experience, the installation of an external heart pump and the drug that allowed him to safely go home with his native heart. A Nebraska woman named Jordan Karle told of losing her younger brother and nearly losing her baby boy.

“Not having access to this drug could be a potential death sentence for my son,” she said.

By a 10-6 vote, the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee gave a nonbinding recommendation in favor of elamipretide.

But aside from the anecdotal testimony, Stealth BioTherapeutics had a problem. This problem also stood in the way of other treatments for rare diseases. Fewer trial subjects meant less data, which made it harder to persuade regulators. The company says more than 1,300 people have taken elamipretide, but only about 30 people are currently taking it for Barth syndrome.

A few months after the hearing, around May 2025, Walker got a call from someone at the Barth Syndrome Foundation. The FDA had made a ruling. It said the clinical trials had not proven that elamipretide was effective. The application was denied.

In response to an inquiry from The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, a spokesperson wrote that “The FDA is committed to ensuring thorough and science-based review processes for all products.” The federal agency also provided a copy of a letter to Stealth explaining how the studies had failed to show a measurable benefit.

The drug’s proponents argued that better results emerged with more time. Dr. Brian Feingold, a pediatric cardiologist who spoke at the FDA hearing in favor of elamipretide, said one clinical trial’s open-label extension — a continuation of the trial without placebos — showed “truly astounding” improvements.

Stealth had spent more than a decade and more than $100 million developing elamipretide and seeking FDA approval. Now all that work was in jeopardy.

With its future in doubt, Stealth cut 30% of its workforce. Walker braced himself what would happen if the company went under and the medicine ran out.

A girl named Hope

At a house on a hill outside Gainesville, about 70 miles northeast of Atlanta, a 4-year-old girl sat at the dining room table, having a snack of popcorn and apple slices. Her name was Hope Filchak. She was deaf in one ear, and with the other she liked listening to Taylor Swift. Hope was completely blind in her left eye. She had some vision in her right eye, but the pupil had an unusual shape, almost like a keyhole.

Hope was born with an ultrarare condition called MLS syndrome. It shares some symptoms with Barth syndrome: poor mitochondrial function, heart trouble, low energy. Early in 2024, her heart was declining. Sometimes she slept 17 hours a day. At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, her parents got a recommendation: Hope could try elamipretide. As it was for other patients taking it under the expanded-access program, the drug would be free of charge.

Elamipretide stabilized her heart, her parents say. It helped her not to sleep so much. And it drew her mother and aunt into the battle for FDA approval.

The sisters, Caroline Filchak and Haley Bower, are executives for a family-owned business called Clipper Petroleum, a fuel distributor and convenience-store chain based in Flowery Branch. They know how to get things done. And so, after the FDA declined to approve the drug in May, Bower began reaching out to politicians.

U.S. Rep. Buddy Carter, Republican of Savannah, is a member of a House subcommittee on health and a former pharmacist. He met with the sisters and took up the cause. By the end of June, in a rare show of bipartisan cooperation, all 14 of Georgia’s members of Congress had signed a letter urging the FDA to consider approving elamipretide.

Through July, political pressure mounted on the FDA. Bowen said that she and the Barth Syndrome Foundation worked to persuade more than 100 members of Congress.

But in early August, the Barth community got more bad news. The FDA had declined Stealth’s request to reconsider its decision. On a call with elamipretide advocates, an official from Stealth said the money was dwindling. They would soon send in another application to the FDA, but they couldn’t guarantee they’d keep operating past September.

In desperation, a Mississippi woman named Kristi Peña wrote a letter to FDA Commissioner Martin Makary. It said, in part, “Will you be the one to save babies lives??”

Peña sealed the letter in a blue envelope and put it in the mail. A few days later, she got an email: an invitation to apply for a face-to-face meeting with Makary. She filled it out.

Meanwhile, another plan was developing. Dubuque’s son, Declan, depended on elamipretide. She contacted others, including Walker, about going to Washington to stage a demonstration. Walker agreed. They booked their flights.

Mr. Burger goes to Washington

Outside the White House on Aug. 20, Walker wore a straw hat with an American flag emblem. Sometimes he held a sign that said ASK ME ABOUT HOW ELAMIPRETIDE CHANGED MY LIFE. He was also photographed holding Jaylen Karle, a 1-year-old boy from Nebraska who nearly died before he started taking the drug.

“If you find each other, you can help each other,” Dr. Barth had said. Walker felt a special responsibility. Bowen’s sons were gone. He was sure they would have joined in this mission if they could have, and so he was standing in for them. Filling their shoes. Then there were the babies: Jaylen and Declan and others. He was standing for them, too, showing their mothers how their lives might look if they survived childhood.

Peña checked her email. Her request was approved. She and Walker and Dubuque and Karle and four others had been granted a meeting with Makary.

Two days later, they all went to FDA headquarters in Maryland. They entered a conference room. Makary introduced himself as Marty. They had half an hour.

There were so many things they could say. So many stories about their children, about their lives before and after elamipretide. Walker was the only one in the room who actually had Barth syndrome, and so it made sense to talk about him.

They had noticed something that week in their travels around Washington, in the long walks from one place to another. Walker kept walking. He was not too weak or too slow anymore. And he did not just keep pace. He kept getting ahead of them, pulling away as they tried to keep up. Did elamipretide really work? The officials needed evidence. Here it was, staring them in the face.

It had all been a trial for Walker. All those years without the drug, and all those years with it, the dividing line sharp and unmistakable. One day long ago, a boy collapsed on the carpet and fell asleep. He woke up, stood up, prayed for something better. And held on for dear life until it arrived.

UPDATE:

On Friday, hours after this story was published online, the FDA announced it had granted accelerated approval to treat Barth syndrome with elamipretide for patients weighing more than 65 pounds, citing the drug’s “likely” benefit. But the approval also requires Stealth to conduct an additional clinical trial. In the meantime, Stealth said it will continue to provide “compassionate access” of the drug for children who don’t meet the weight threshold.