Could world’s first nuclear-powered merchant ship become a Georgia museum?

BALTIMORE ― What was once perhaps the most celebrated ship in the world today floats at the Port of Baltimore, guarded only by a pothole-pocked road and GPS-mapping confusion.

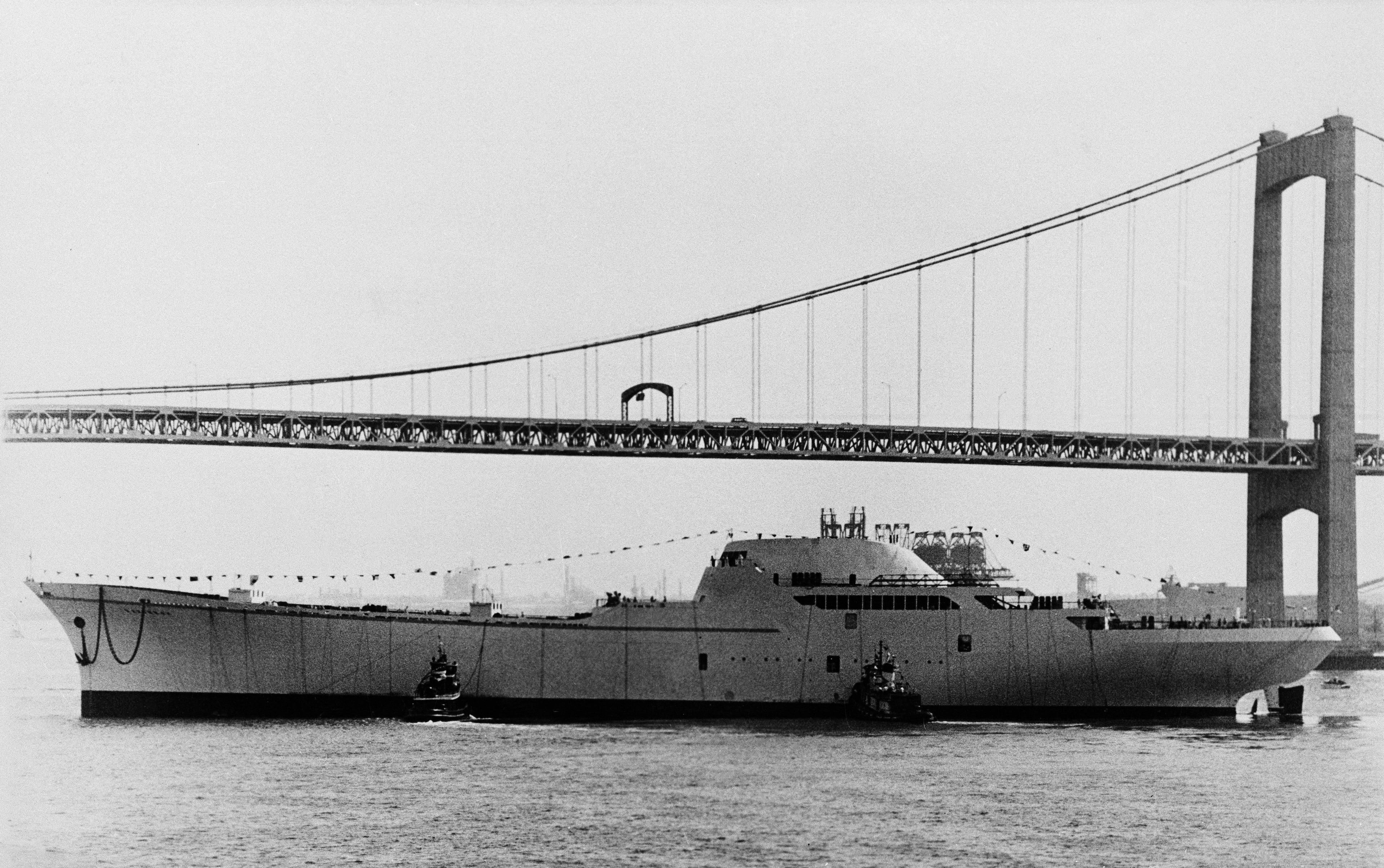

The NS Savannah is the first of only three nuclear-powered merchant vessels ever built. Like its namesake SS Savannah, the first steam-powered vessel to cross the Atlantic Ocean, the NS Savannah was a global phenomenon. Between 1962 and 1970 it traveled 458,000 nautical miles, entertained 848 passengers (including two kings) in stylish comfort, hosted nearly 1.4 million visitors while in port and carried cargo between the U.S. and Europe.

The ship, commissioned by President Dwight Eisenhower to demonstrate atomic energy’s future stretched beyond bombs, is now lashed to Pier 13 — not far from Baltimore’s trendy Inner Harbor but far enough. Its off-GPS address is a wharf squeezed between a cargo container terminal and an elevated highway.

An informal coalition of Savannahians has a new home in mind for the NS Savannah. Led by John Cay, a prominent insurance broker and real estate developer, the group is exploring turning the ship into a floating museum and special events venue at a slip next to the Savannah Convention Center.

Cay and other Georgia boosters are in talks with the ship’s caretaker, the U.S. Maritime Administration, about moving the NS Savannah south in the next two years. The Maritime Administration’s Erhard Koehler told visitors at a recent open house aboard the ship that the Savannah group is “well advanced” in its effort.

It would represent a homecoming of sorts for the storied ship. After the NS Savannah was retired, it was first docked in Savannah during the early 1970s before being moved to other Eastern Seaboard ports in a decadeslong search for a final resting place.

The NS Savannah would need to be towed. The Maritime Administration removed the remnants of the vessel’s nuclear reactor in 2022. The five-year project cut into the heart of the ship — through a 2-foot-thick collision-protection barrier made of layers of steel, concrete and redwood lumber — to dismantle equipment designed to contain radioactivity.

The decommissioning also required several onboard modifications to support the nearly 100 workers involved in the removal. Improvements included new climate control and sanitation systems and mechanical equipment, transforming one of the cargo holds into a theater-like training center and renovations for office and administrative spaces.

The NS Savannah’s standing as a National Historic Landmark also qualified it for National Park Service funds to restore the public spaces, such as the passenger lounge, lobby, dining room and staterooms.

Those enhancements make the ship “turnkey museum-ready,” Koehler said, and have allowed for regular public open houses over the last two years. A recent visit day drew more than 400 advanced reservations and prompted the nonprofit that was started to support the ship, the NS Savannah Association, to cap RSVPs two days beforehand.

“People love her,” said Bob Adams, the NS Savannah Association president. “She’s a Goldilocks: Not too big to explore, not too small to feel cramped. She’s just right — and oh, so beautiful.”

Time capsule

Aesthetically speaking, the NS Savannah remains the showstopper that once drew VIP welcomes and above-the-fold newspaper coverage at every port.

The vessel’s sculpted lines accentuate its 596-foot length, and the Maritime Administration keeps its crisp white paint job fresh. Its design serves its dual purposes — part cruise ship, part cargo freighter — and makes it instantly recognizable, as does the attention-grabbing “Atoms for Peace” symbol painted prominently on the NS Savannah’s superstructure.

Onboard, the passenger areas are decorated in a midcentury modern style. Linoleum tile flooring. Seating upholstered in colored Naugahyde. Polished brass fixtures. And, true to the time of the ship’s heyday, lots of ashtrays — built into cocktail tables and mounted on walls, even in the waiting room of the vessel’s hospital.

The ship accommodated 60 passengers in 30 staterooms during its five demonstration voyages, visiting 35 ports in 14 countries over a three-year period. Travelers ate in a dining room dominated by a wall-sized sculpture mural representing the artist’s interpretation of nuclear fission. Up on the promenade deck, they toasted each other with Atomic Cocktails (equal parts vodka, brandy, dry sherry and Champagne) in the bar and danced the Boogaloo in the lounge. They made plans for their days on a plush, twisting couch in the lobby.

The boarding stairs act as a space-and-time wormhole for newly arrived visitors, who do double takes over the ship’s interiors and chuckle at the sound of Neil Sedaka’s 1961 hit “Calendar Girl” playing faintly over the vessel’s sound system. One of the tour guides, Sam Cox, visited the NS Savannah as a 10-year-old when the ship called on Baltimore in 1964. He doesn’t remember much from that visit, only that the environment still feels familiar.

“Welcome to our time capsule,” Cox said.

Right ship, right place, right time

For the NS Savannah and the U.S. Maritime Administration, this is decision time.

The removal of the ship’s remaining nuclear components cleared the way for the federal government to dispose of the vessel through one of three options: preserving it, dismantling it to sell off scrap metal or sinking it offshore as an artificial reef.

“The National Historic Preservation Act says minimize harm, that a federal owner of a landmark should not destroy it if there is any reasonable alternative to destruction,” Koehler said. “And that is what we’ve been seeking.”

For Savannah, the city, the timing is serendipitous.

The Savannah Convention Center’s $276 million expansion finished earlier this year, doubling the facility’s capacity, and construction will soon begin on a 400-room Signia by Hilton next door. That hotel, slated to open in March 2028, fronts on a Savannah River inlet known as Slip 3.

Slip 3 is some dredging work away from accommodating a vessel the size of the NS Savannah. The hotel developer, Atlanta-based Songy Highroads, has shown interest in the ship’s potential for hosting events and meetings and perhaps even renting some of the 30 staterooms for accommodations. The Savannah Convention Center’s event planners also find the onboard spaces attractive.

The NS Savannah’s main use would be as a museum ship — the rare missing amenity among Savannah’s tourism offerings. Currently, only water taxis and party boats designed to look like paddle wheelers operate on the waterfront.

“From a tourism perspective, a ship museum is the one thing Savannah doesn’t have,” said Cay, who recently opened a marina and a mixed-use development near Slip 3, “and there’s opportunity there considering our history as a port city.”

Savannah is the Southeast’s busiest commercial port, with dozens of the cargo container ships calling weekly at the Georgia Ports Authority docks just upriver from downtown. The city also is home to a popular maritime museum, Ships of the Sea, which operates from a residence constructed in the early 1800s for the builder of the SS Savannah.

The Ships of the Sea is “all in” in support of the NS Savannah’s relocation to the city, said museum director Molly Carrott Taylor. She facilitated the initial talks about the idea after meeting the NS Savannah’s Koehler at a 2024 maritime museum conference.

Those familiar with museum operations project annual expenses would exceed $1 million. A veteran museum ship operator, Jay Martin, noted the high costs associated with water-based exhibit halls. Power, water, sewer and other infrastructure must be connected to the shore, in addition to maintenance and restoration outlays.

“A historic ship is one of the most expensive museum projects you can undertake,” said Martin, who has managed three ship museums in his career. “But the balance sheet can be managed and ship museums can be of great value to their communities.”

Martin is the current director of the Battleship North Carolina, a World War II naval vessel. Based in Wilmington, North Carolina, since 1962, the ship attracts nearly 250,000 visitors a year and hosts a number of special events. The North Carolina is owned by the state but is self-sustaining, generating enough revenue to cover its $3.5 million in annual operating expenses.

Savannah officials have been talking with Martin on the NS Savannah. He’s bullish given Savannah’s well-established tourism economy and connection to a commercial port.

Bert Brantley, the Savannah Area Chamber of Commerce president, is an important ally, while acknowledging a bid is still in the preliminary stages.

Senior city and county government staffers and the convention center authority are aware of and not opposed to the proposal.

“Savannah’s a logical fit for an orphaned ship,” Cay said. “Let’s bring her home.”

History of the NS Savannah

The Nuclear Ship Savannah is the first nuclear-powered surface vessel ever made and one of only three nuclear-powered merchant ships in existence. The NS Savannah was conceived to demonstrate the potential for atomic energy beyond weaponry and its reactor was used to heat water and produce steam for the ship’s propulsion.

Here are key dates in its history:

1953 — President Dwight Eisenhower announces the Atoms for Peace program in a speech at the United Nations. The initiative meant to transform the atom from a scourge into a benefit for mankind.

1955 — Eisenhower commissioned the NS Savannah as the world’s first nuclear-powered passenger and cargo-carrying ship.

1959 — First lady Mamie Eisenhower christens the NS Savannah at its launch.

1962 — The NS Savannah enters service and visits Savannah during its maiden voyage.

1964 — The NS Savannah visits foreign ports for the first time. The ship hosted three heads of state during its international tours.

1965 — The NS Savannah ends passenger service after visiting 35 ports in 14 countries and transitions to freighter duty, carrying cargo between the United States and Europe.

1970 — The NS Savannah ends commercial service and the U.S. Congress suspends funding for the Atoms for Peace program.

1971 — The ship’s reactor is shut down and defueled.

1972 — The NS Savannah is moved to Savannah to become the centerpiece of a planned Eisenhower Peace Memorial. The project stalls and is later abandoned.

1975 — The NS Savannah relocates to Charleston, South Carolina for storage.

1982 — The NS Savannah debuts as a museum ship at Charleston’s Patriot’s Point, home of the World War II aircraft carrier the U.S.S. Yorktown.

1989 — Hurricane Hugo strikes Charleston and floods the NS Savannah with rain and seawater. Much of the ship is closed off to visitors because of mold and mildew issues.

1991 — The NS Savannah is named a National Historic Landmark.

1994 — The U.S. Maritime Administration moves the NS Savannah away from Charleston at Patriot’s Point’s request. The ship is initially dry-docked for repairs in Baltimore then stored with the other vessels in the James River Fleet near Norfolk, Virginia.

2008 — The NS Savannah is moved to Baltimore’s Pier 13.

2017 — Removal of the nuclear reactor and the nuclear containment vessel commences and stretches through late 2022. A number of improvements are made to the ship’s interior as part of this decommissioning process.

2024 — The NS Savannah program manager begins searching for a future home for the ship in anticipation of a disposition order. This mandates vessels either be donated or chartered for a preservation purpose, such as a museum; dismantled for scrap; or sunk offshore as an artificial reef.

(Compiled by Adam Van Brimmer/AJC)