Fantastical ‘Lost World’ of Minnie Evans on view at High Museum

Though her work trafficked in the fantastical and visionary, self-taught artist Minnie Evans was grounded in the day-to-day reality of her Southern hometown of Wilmington, North Carolina.

That treatise is one of the many insights into Evans’ life and work tackled in an important retrospective at the High Museum, “The Lost World: The Art of Minnie Evans,” the first major exhibition of her work in 30 years.

The exhibition comes at a time of renewed interest in women visionary artists, including Swedish abstract artist Hilma af Klint and British spiritualist artist Georgiana Houghton. At the heart of this interest is an examination of where the artistic impulse comes from and how it is either explained or — in some cases, with self-taught and women artists ― diminished.

In an unprecedented win for the High Museum, the exhibition leaves in April 2026 and travels to New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, where, in 1975, Evans was among the first Black artists to have a solo exhibition there.

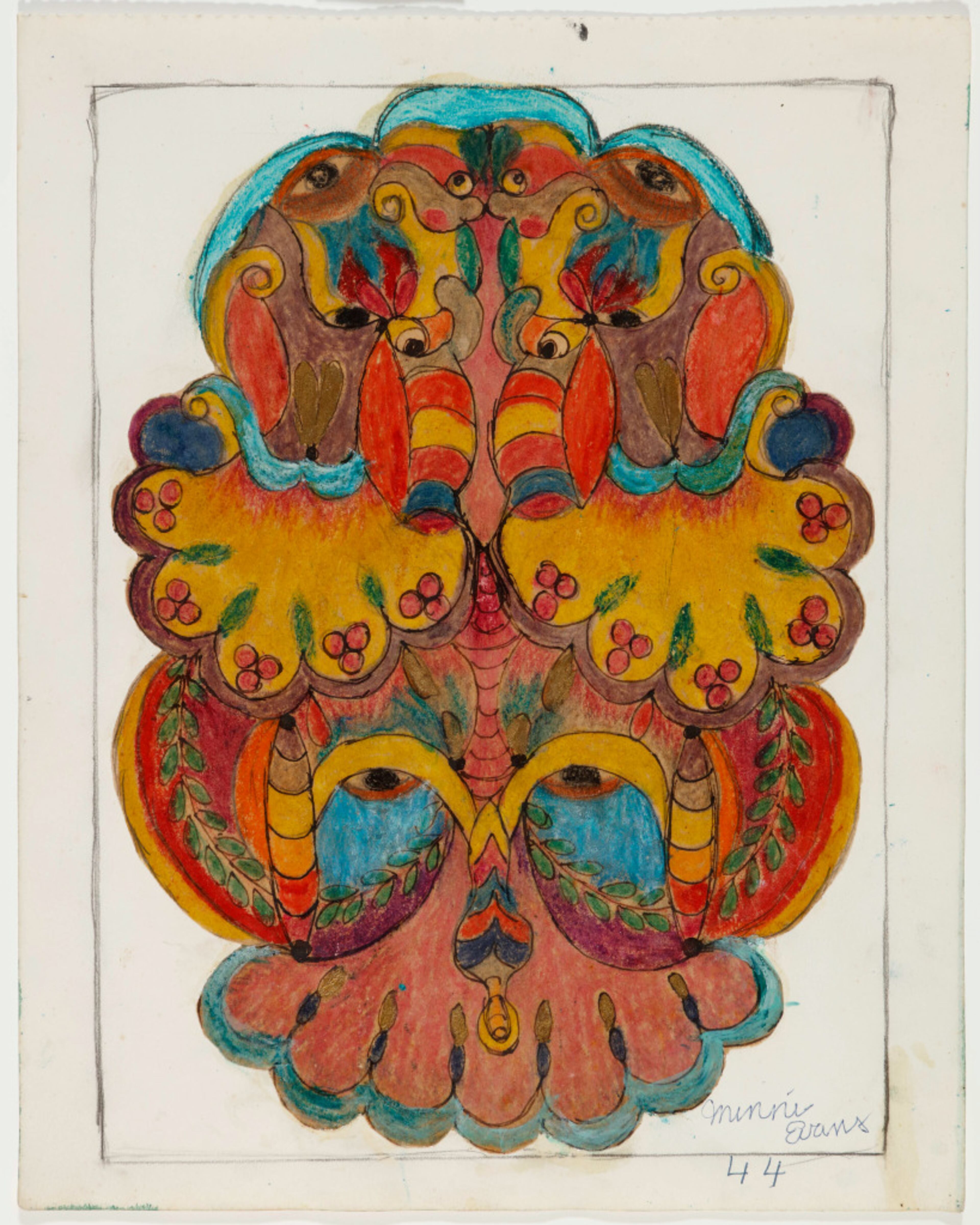

From early drawings done in her favorite medium of Crayola crayons to later collage works that explode with color and detail like a garden bursting into exquisite bloom, the more than 100 works in “The Lost World” show an artist endlessly inspired, growing, and driven to create works of delicious excess and strangeness.

There is a conventional view of self-taught artists that they exist in a kind of creative bubble, making work in isolation and creating in a way that is out of step with the world around them, said Katherine Jentleson, senior curator of American art and curator of folk and self-taught art for the High.

“The Lost World” in part debunks that impoverished view of the genre.

“Self-taught artists never operate in a vacuum,” said Jentleson, who challenges that idea throughout this revelation-filled exhibition.

“The Lost World” also serves to trace the arc of Evans’ creative evolution. As her life changed, her work changed with it.

“The Lost World” delves into Evans’ relationship to her employers, her family, her hometown and the historical forces that shaped it.

Evans was a devout Methodist who read the Bible but also Edith Hamilton’s “Mythology,” said Jentleson. She loved history and found inspiration in B-grade Hollywood productions like the 1940 serial film “Drums of Fu Manchu,” which featured a plot with ancient tablets and writings. It was an idea that Evans incorporated into many of her later drawings that featured flourishes of cryptic language and visual codes. In addition, a male figure with distinctive Fu Manchu-style facial hair often pops up in her drawings.

The first room of “The Lost World” includes a glass display case featuring photos and media that tell the story of Evans’ origins. There is an aerial photograph of Wilmington and an image of Evans standing alongside some 30 fellow servants from her time working as a domestic. Also included is the first drawing Evans created.

“My Very First” from the Whitney collection is a 1935 ink drawing of repeated looping forms that Jentleson describes as “curvilinear” flourishes. Evans said the work arose from visions she had experienced since childhood but that intensified with the death of her beloved grandmother.

“She described this as when she really started heeding her visions to make art,” said Jentleson.

The exhibition takes its title from the “lost world” that existed before the biblical flood described in the Book of Genesis. Evans claimed she had visions of that time that compelled her to create.

Whether Evans experienced visions or simply operated from the usual urges and inspiration of any creative is one of the tantalizing mysteries that surrounds her work.

“[For] Black artists who describe visionary practices, visions become a way to justify what you’re doing, right? They become a way to make it make sense to yourself, especially if you’re a religious person,” said Jentleson.

Evans’ often maximalist, intricate, complex works suggest a layered salad of Rorschach test, psychedelia, Hindu art and Buddhist mandalas. They underscore how the bedrock of human existence — the religious texts, Greek and Roman mythologies, fairy tales — have their own strain of excessive flights of fancy. If anything, Evans feels like a conduit for some of human history’s most imaginative tendencies as seen in the cartoonishly terrifying pachyderm creatures she draws in her depiction of the biblical apocalypse.

Evans was a product of her environment, and events that marked her early life are reflected in her work. In 1898, a mob of white supremacists burned down the office of Wilmington’s Black-owned newspaper; attacked African Americans in the streets, killing an unknown number of them; forcibly removed Black elected officials from office; and banished Black residents from Wilmington.

According to Atlanta filmmaker Brad Lichtenstein, who produced and directed the documentary “American Coup: Wilmington 1898,” many Black families fled to a cemetery during the riot and stayed there for many nights in the freezing cold.

Evans, who was 5 years old at the time, had a cousin who was shot in the violence and whose family later fled North.

“If you didn’t know someone who was killed, you knew someone who was banished. … At the time, if you were Black, there’s no way you weren’t impacted by the coup and the massacre,” said Lichtenstein.

Jentleson noted that figures hiding in graveyards can often be seen in Evans’ drawings.

Evans married at age 16 and worked for the majority of her life as a domestic for wealthy Wilmington landowners Sarah and Pembroke Jones.

Jentleson speculates that it was in that home where Evans might have been exposed to a vast art collection that informed her work. Some have also speculated that the repeated motif of eyes gazing out from Evans’ drawings might also have been inspired by the experience of a Black domestic worker in the South under continual surveillance.

When the Jones family’s estate changed hands, Evans moved down the road to an adjoining property that Sarah transformed into a sprawling garden. In 1948, Evans became the gatekeeper at Airlie Gardens, where she worked for 25 years.

“Becoming the gatekeeper was really when her art flourished,” said Jentleson.

She was paid a pittance, but the gatekeeper job allowed her the freedom to explore the garden with its 75,000 azaleas and the time to draw and sell her drawings to locals and visitors. The deep impact of the natural world is apparent in her later work, in which butterflies, trees and flowers of every kind edge their way into her seductive world. Many of her works feel intrinsically botanical, suggesting germination, growth and the endless replications of the natural world exploding in glorious color onto her pages.

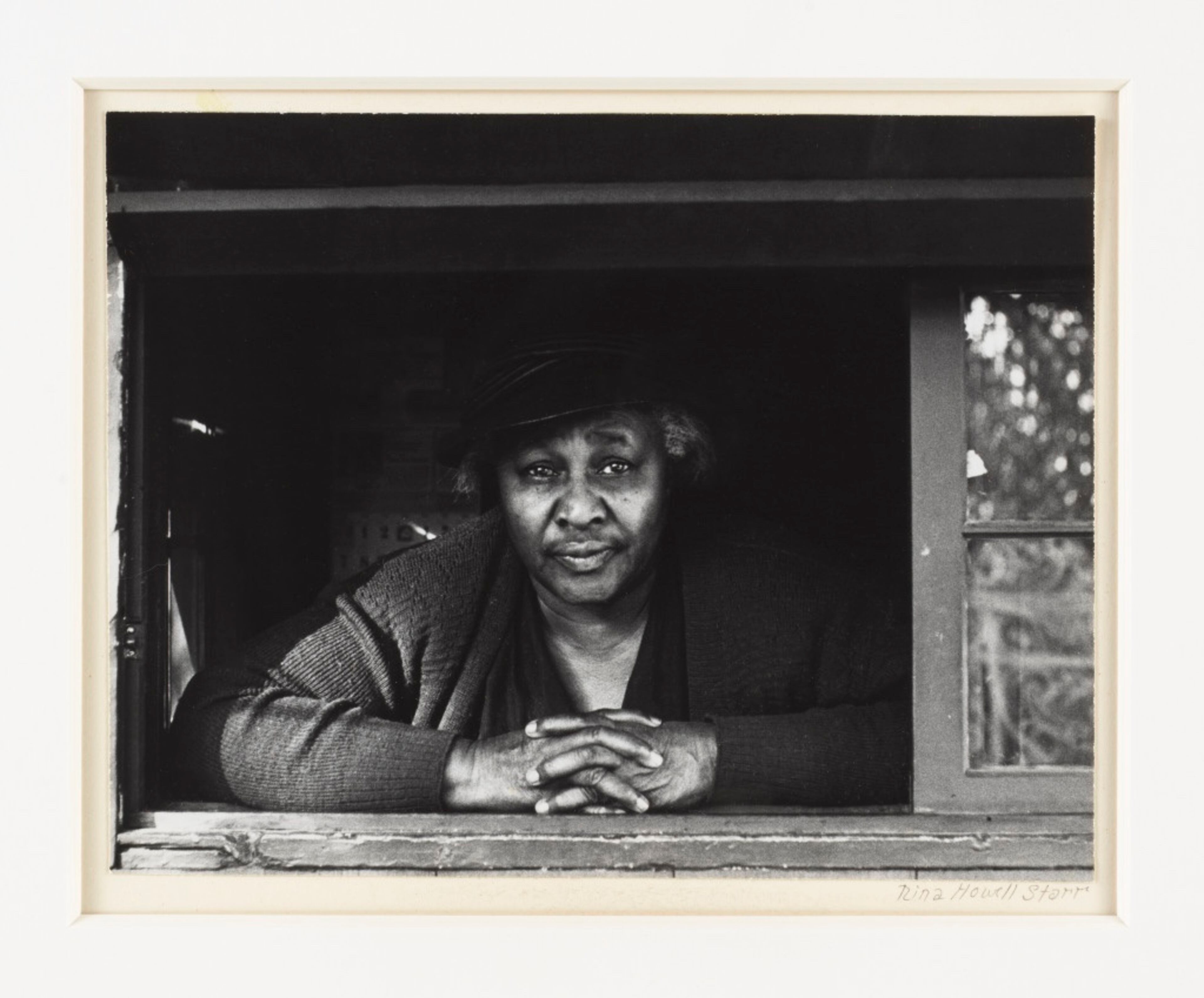

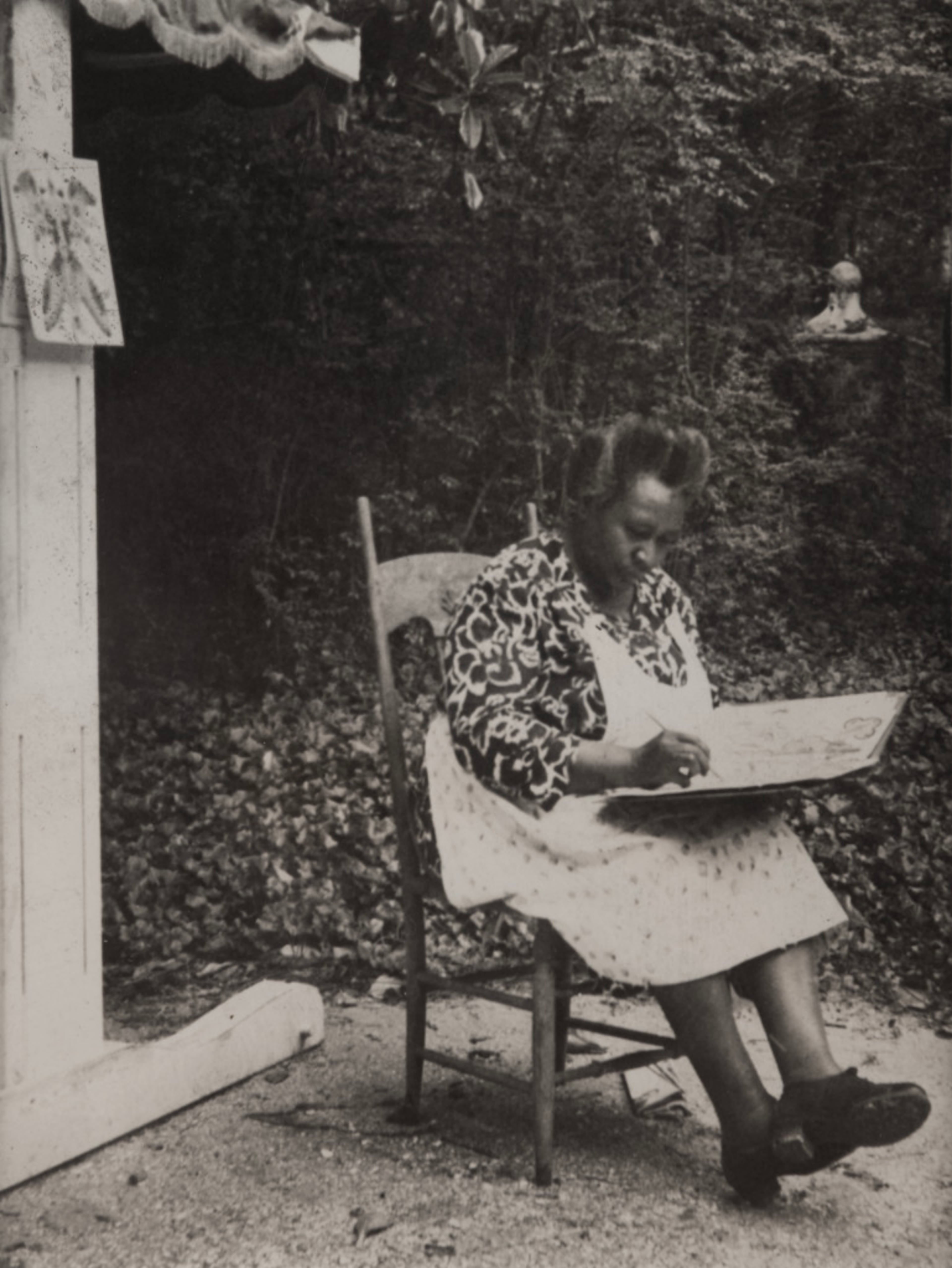

“The Lost World” is distinguished by a wealth of photographs of Evans, including one of her sporting a neat-as-a-pin updo and white apron to protect her dress while sitting in a wooden chair, sketching intently. Whatever her inspiration ― divine, human, nature or some combination of all three ― Evans’ work still has the power to knock you out with its strangeness and imagination.

ART EVENT

“The Lost World: The Art of Minnie Evans.” Through April 19. $23.50. High Museum of Art, 1280 Peachtree St., Atlanta, 770-733-4400. high.org.