MARTA was meant to go more places. Here’s why it doesn’t.

MARTA is at a crossroads.

Its top official resigned earlier this year, an unexpected departure that, while welcomed by some after months of mounting service issues, nevertheless thrust the transit agency into uncertainty at a critical time.

MARTA is nearing completion of a half dozen or so long-awaited projects, the largest capital investments set to be delivered in more than a decade — sleek new train cars, the first major redesign of the bus network since MARTA’s creation, the region’s first rapid bus line and a new tap-to-pay fare system, among others.

By next April, when all those changes are set to be in effect, MARTA leaders have said the transit agency will look completely different from today. And how it looks today is largely the same as it did more than two decades ago, when the last major construction project wrapped up and the last new rail station opened.

Big ideas have been floated in the years since the North Springs station opened in 2000.

MARTA took ownership of Atlanta’s streetcar and drafted plans to expand it. Clayton County residents voted to join MARTA, partly out of a desire for rail. And Atlanta residents taxed themselves to pay for additional transit projects.

But for a host of reasons, many of those efforts have been scaled back or reconsidered, all while the region continues to grow and congestion worsens.

Atlanta is rated the eighth most congested urban area in the United States, but most with the option still pick traffic over MARTA’s often unreliable bus and rail service. Its rail ridership is half what it was before the pandemic, putting MARTA second-to-last among the 10 largest transit agencies in the country when it comes to recovering ridership.

It’s a similar struggle that has beguiled MARTA for all of its existence.

One of the earliest plans called for a system with 97 miles of rail crisscrossing the five metro counties surrounding Atlanta, “capable of indefinite extension.” The key to that success, planners noted, would be attracting and keeping riders.

That plan, and other ambitious plans after it, never came to fruition. The current rail system is less than half that size and traverses just two counties.

Interim General Manager and CEO Jonathan Hunt acknowledged earlier this month that missed project deadlines have left many doubtful about future expansion efforts. But he told attendees at a transit forum that MARTA is committed to growth.

“We want to envelop the city in transit,” he said.

Whoever MARTA’s board of directors hires next as the new CEO, they will play a consequential role in determining how — and whether — the transit system expands over the next few decades.

As history shows, it’s a big ask.

_

End of an era

Railroads created Atlanta, but cars have dominated since at least the 1920s.

Car ridership surpassed that of streetcars for the first time during that decade, a moment marked by Clark Atlanta University historian Howard Preston in his book on the origin of Atlanta’s automobile age. Car travel has dominated ever since.

Before then, most folks traveled by streetcar. More than 200 miles of track stretched across the region by 1914, according to a study for the Georgia Department of Transportation. Lines extended as far out to Marietta, Stone Mountain and College Park.

By 1949, the last streetcar traveled its final route as riders sang “Auld Lang Syne.”

“An era ended,” The Atlanta Constitution reported. Among the passengers was a police officer who rode one block “just to say he had” and a couple who’d met and fallen in love on the streetcar 25 years earlier.

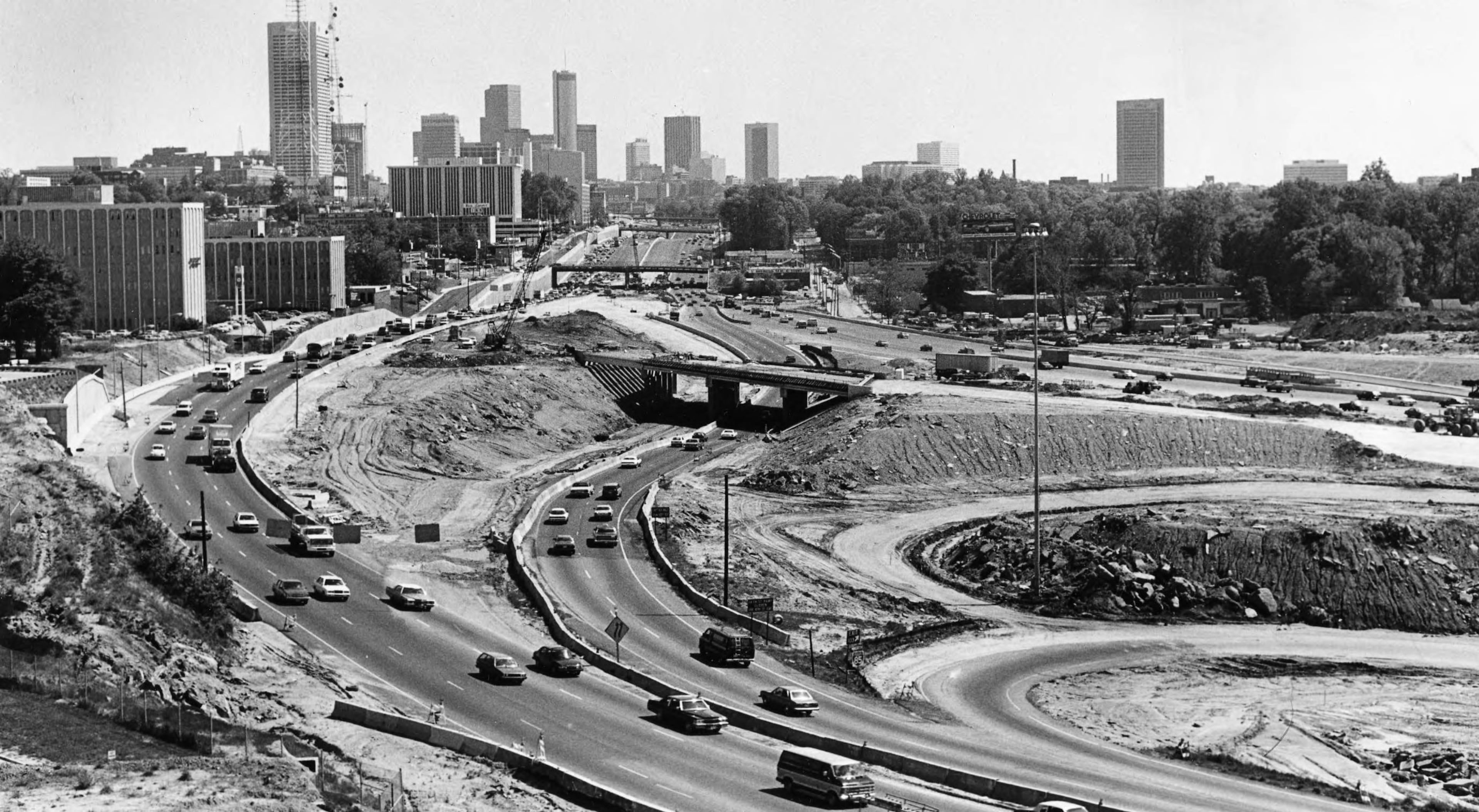

Construction on the Downtown Connector had already begun and continued throughout the 1950s. But even before it was complete, regional planners were warning it wouldn’t meet the city’s needs by 1970.

“We would need 120 expressway lanes radiating to and from central Atlanta, and a 28-lane Downtown Connector,” a 1960 Metropolitan Planning Commission report said. “This is, of course, a physical impossibility.”

Rapid transit was a necessity, they said. The system should be “a regional system from the beginning,” the planning commission reported. A series of “spokes and spurs” radiating from downtown Atlanta to Marietta, Sandy Springs, Norcross, Clarkston, Forest Park and elsewhere was proposed.

The planners laid out “essential characteristics” for success, among them: the ability to attract and keep riders, a “pleasing appearance” and exclusive right-of-ways separate from other traffic.”

And they cautioned “appeals to conscience or civic-mindedness will not switch people to more efficient forms of transportation. Only better service will do this.”

Planning continued the following year, and a new goal was set: 66 miles of dual-track rail with 42 stations, all to be built by 1980.

‘A 6-wheeler with 4 missing’

Design: Jessi Esparza / AJC | Source: MARTA, Atlanta Regional Commission

Plans inched forward with the General Assembly’s 1965 vote to create MARTA, but Atlanta and five surrounding metro counties still had to ratify its creation.

The Constitution reported an unprecedented “wall of unity” among political and business leaders in Atlanta and most of the counties, who saw transit as protection against “strangulation by traffic.”

That wall of unity didn’t extend to the fifth metro county, Cobb. Voters there rejected the invitation to join.

Unity crumbled further when voters were asked to fund the system in 1968. Atlanta voters and those in DeKalb and Fulton counties said no.

“There’s no point in acting as though it’s business as usual because it ain’t,” Henry Stuart, MARTA’s general manager, told a Constitution reporter the day after the vote. “It’s about as bad as it can be.”

White suburbanites in Cobb County killed the original measure. But leading the opposition in 1968 were members of Atlanta’s Black community, who said MARTA’s plans didn’t do enough to serve them.

The matter came back before voters in 1971, this time with promises to drop fares from 40 cents to 15 cents and make immediate improvements to bus service, measures called for by Black voters. The previous 66-mile plan was scaled back to just over 54 miles.

The referendum passed in DeKalb and Fulton counties and in Atlanta, but failed in Clayton and Gwinnett counties, where officials felt that not enough service was proposed to justify the cost to taxpayers. Within its first six years, the “regional” transit agency authority extended over just a fraction of the metro.

It was, as the Constitution put it, “A 6-wheeler with 4 missing.”

‘Only the gods’ know how much it will cost

The successful 1971 vote allowed MARTA’s board to move forward, but the rejections by Clayton, Cobb and Gwinnett voters forever changed how the system would look.

With Clayton out of the picture, the southern line to Forest Park was shortened.

Without Cobb, the northwest line to Marietta was cut.

Without Gwinnett, the northeast line to Norcross was trimmed.

Design: Jessi Esparza / AJC | Source: MARTA

The chair of MARTA’s board said he was sorry the counties opted out.

“But right now, we’re going to push ahead with building the nation’s best rapid transit system,” Roy Blount told the Constitution.

Hitting a 1980 target completion date hinged largely on receiving federal grants. The Constitution was grim about Atlanta’s chances, saying MARTA had “a snowball’s chance in hell” of getting all the money it needed because of intense competition from other cities.

Washington, D.C., and San Francisco broke ground on rail systems of their own first, leading what a national association for transit called a “renaissance of rail” prompted by rising fuel prices during the 1970s energy crisis.

MARTA lucked out when Seattle voters rejected a transit plan. The federal grants earmarked for that project came south instead. By 1975, MARTA had secured $800 million in federal grants, a fraction of the estimated $2.1 billion needed.

While it fell short of full funding, Atlanta’s share marked the single largest federal commitment to transit made to any city. From 1973 to 1980, MARTA received more than a third of all the federal capital funding.

But costs continued ballooning through the 1970s, complicating and delaying construction. One of MARTA’s engineering consultants said “only the gods” know the final price tag. The target completion date moved to 1985.

“That all-important public relations evidence of progress — holes in the ground — has been sadly lacking,” the Constitution wrote.

MARTA pledged to move faster.

“We are going to show so much progress that people are going to ... complain ... about the dust and mud from our construction,” said John Wright, the board chair at the time.

Soon, the competition date moved back again, to 1989.

‘More of a success than any of them’

Design: Jessi Esparza / AJC | Source: MARTA

The first rail line opened in June 1979 — 6.7 miles stretching from Avondale to the Georgia State station.

It was, a reporter noted, “exactly seven years, seven months and 21 days” after voters approved the system in 1971.

Behind schedule or not, the first train marked a major milestone and set the region apart: No other southeastern city could boast of a rail system.

By the end of the year, what’s now the Blue Line extended to H.E. Holmes station.

Within two more years, the system had begun to spread north and south, but MARTA was still struggling to find the money to pay for the full expansion. In 1982, MARTA’s general manager told the Constitution it would be able to finish laying tracks between East Point and Brookhaven, but “that’s it for the foreseeable future.”

Another round of federal funding ensured the tracks between Chamblee and the airport were completed on time, marking the end of construction in the 1980s. President Ronald Reagan’s administration had soured on new rail systems, but MARTA was still seen nationally as a success.

The federal transportation chief at the time said the agency was “a model, more of a success than any of them.” It was unique then, and now, as one of the only transit agencies supported by a local sales tax.

As the decade came to a close, efforts ramped up to entice Gwinnett to join the system. Northern stations had become popular for commuters outside MARTA’s service area, with the transit agency reporting roughly one-third of weekday travelers at the Brookhaven station coming from either Cobb or Gwinnett.

But the vote in 1990 failed again, with racist arguments against transit resurfacing.

“One of the worst fears is bringing people out of Atlanta, the minorities,” a county commissioner said at the time. MARTA would bring “the wrong people” to Gwinnett, one resident said in a town hall meeting before the vote.

Roughly 70% of voters rejected the expansion, which would have added 10.8 miles of rail, more than the 1971 plan had proposed.

‘The largest movement of humanity’

Design: Jessi Esparza / AJC | Source: MARTA

By 1992, 34 miles of track and 30 stations had been built, including the first spur that created what’s now the Green line.

Planners laid out what they hoped to see next: A new northern branch, first to the Northside Hospital area and eventually North Springs. A Tucker-North DeKalb line, to bring rail to Emory University and North Druid Hills. Spurs to Hapeville, Northside Drive and another extending the Green line to Perry Homes.

Some materialized, like an extension of the Blue line to Indian Creek. Olympic fervor sped up construction of three new stations along the new northern line, adding stops at Buckhead, Medical Center and Dunwoody. They opened days before The Games began but 18 months ahead of MARTA’s original schedule.

“In our preparation to host the millions of visitors who took over the streets of Atlanta during the summer of ‘96, we have made MARTA a better system for the thousands of residents who ride with us everyday,” Richard Simonetta, then the agency’s head, wrote in a report on MARTA’s Olympics experience.

Never before, or since, has MARTA provided the service it did during The Games. They operated 24-hour service on rail lines and 29 regular bus routes, ferrying 17.8 million passengers. Trains ran every four minutes during peak times. With fewer cars on the road, ozone pollution decreased by as much as 50%, state environmental regulators estimated.

The Constitution gave MARTA an A-minus for its service. “This was the largest movement of humanity since the invasion of Normandy, and Atlanta’s little train and bus system did just fine.”

After The Games, MARTA staff reflected on the lessons learned: Most construction projects, they wrote in a report, “can be achieved more quickly given the right priorities and sufficient resources.”

‘Sometimes a pivot is necessary’

Design: Jessi Esparza / AJC | Source: MARTA, Atlanta Beltline

The last two “new” MARTA stations opened in 2000.

“It’ll be even longer before more stations open,” the Constitution reported. “For the first time in MARTA’s history, no new construction is in the works.”

In the 25 years since, the system has grown, however.

Clayton County voted to join MARTA in 2014, expanding the system for the first time since 1971. But major construction has been limited and moved slower than planned. Tension over delayed projects has led to disputes between MARTA and Atlanta officials, leading to dueling audits and an unresolved debate over $70 million.

But many projects have been abandoned or scaled back.

When Clayton County voted to join, part of the pitch was commuter rail extending south from the East Point station to Lovejoy. But the commuter line was scrapped because of right-of-way issues, and now the agency plans to pursue a rapid bus line instead.

Another promised Clayton project, a rapid bus line to Southlake, also is delayed.

Light rail plans in DeKalb have been scrapped, too. MARTA officials adopted a plan for rail along the Clifton Corridor in 2012 but walked that back in 2018, again because of right-of-way issues. Rail plans in the southern part of DeKalb have also been scrapped.

Atlanta is the only jurisdiction in MARTA where transit options have expanded since the two northernmost stations opened.

MARTA took over operations of the Atlanta Streetcar from the city in 2018, adding a 2.7-mile loop of light rail between Centennial Olympic Park and the Sweet Auburn Historic District to the transit agency’s roster.

Extending the streetcar east and onto the Atlanta Beltline was one of the first projects MARTA pursued after Atlanta voters approved an additional transit sales tax in 2016. That plan is now on hold.

The eventual 22-mile Beltline was envisioned as a light rail transit corridor, but how and whether that happens is up in the air.

Earlier this year, Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens pulled his support for starting on the Eastside trail, proposing instead to start on the Southside. His chief of staff, Courtney English, said this month that the Atlanta Beltline would lead planning for transit along the loop, instead of MARTA.

Eastside light rail construction was on track to break ground in 2026 and begin service in 2028. With the change in plans, light rail on the Beltline is farther off. Dickens has said he believes construction on the Southside could begin by the end of 2029.

In an interview with the AJC’s editorial board just before he stepped down, former MARTA General Manager and CEO Collie Greenwood said ideally, transit planning should operate with a long-range view, unencumbered “by temporal and political influences.”

But he added that it wasn’t his or MARTA’s role to decide what happens with Beltline transit, which is the city’s greatest opportunity to substantially expand MARTA’s service and reach.

“It would make it easier for transit if, when we decided what we were going to do, we actually did it,” he said. “But sometimes a stop or a pivot is necessary.”

MARTA is at a crossroads in search of new leadership at a critical time, with huge projects on the horizon. The Future of MARTA is an occasional series looking at the past, current and future of a transit agency that shapes and is shaped by metro Atlanta.