No body of proof: How Georgia homicide cases are solved without remains

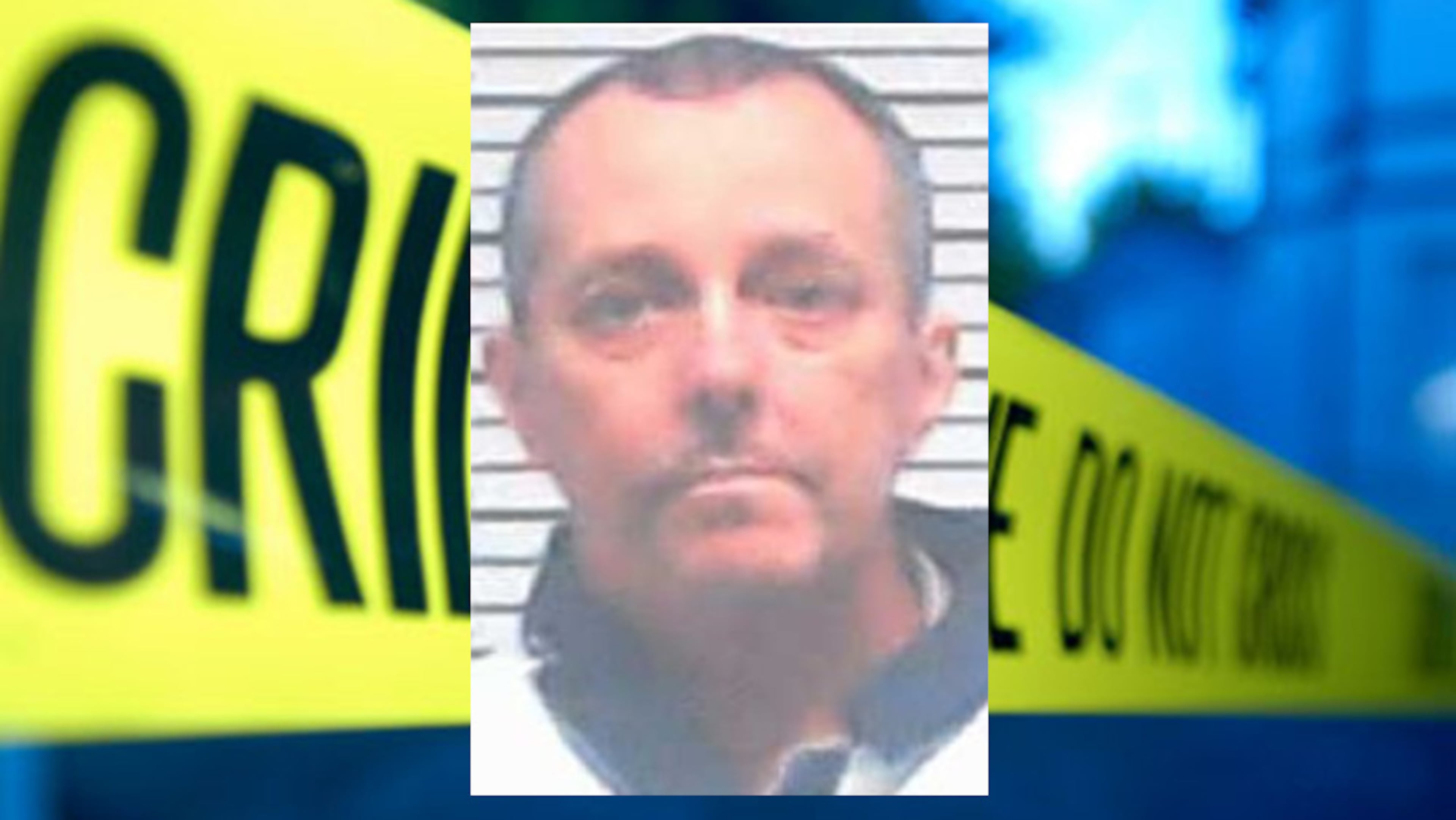

The case file was huge and the evidence overwhelming, according to investigators. When Reginald Robertson’s fiancee disappeared in March 2021, he eventually became the main suspect.

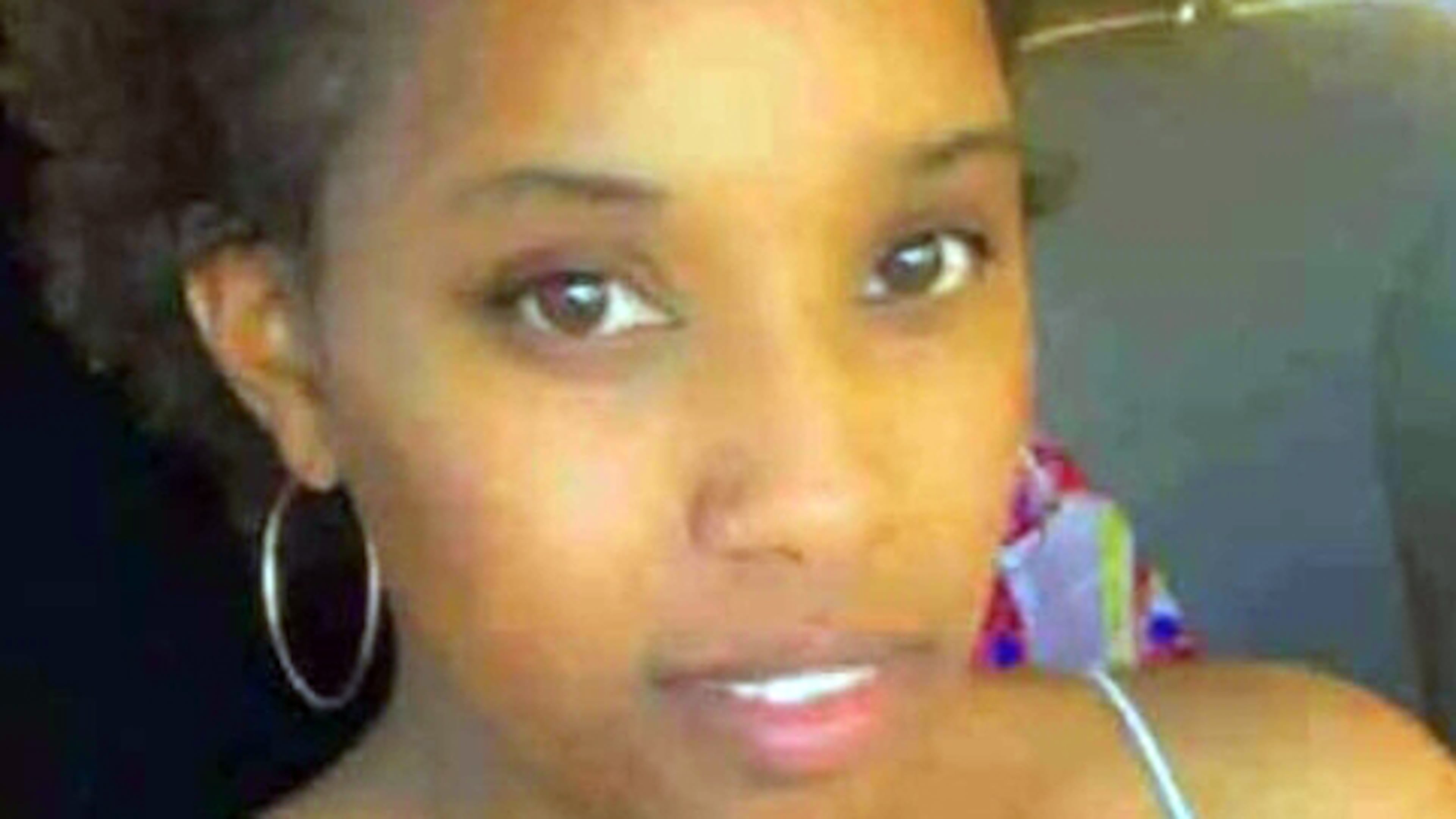

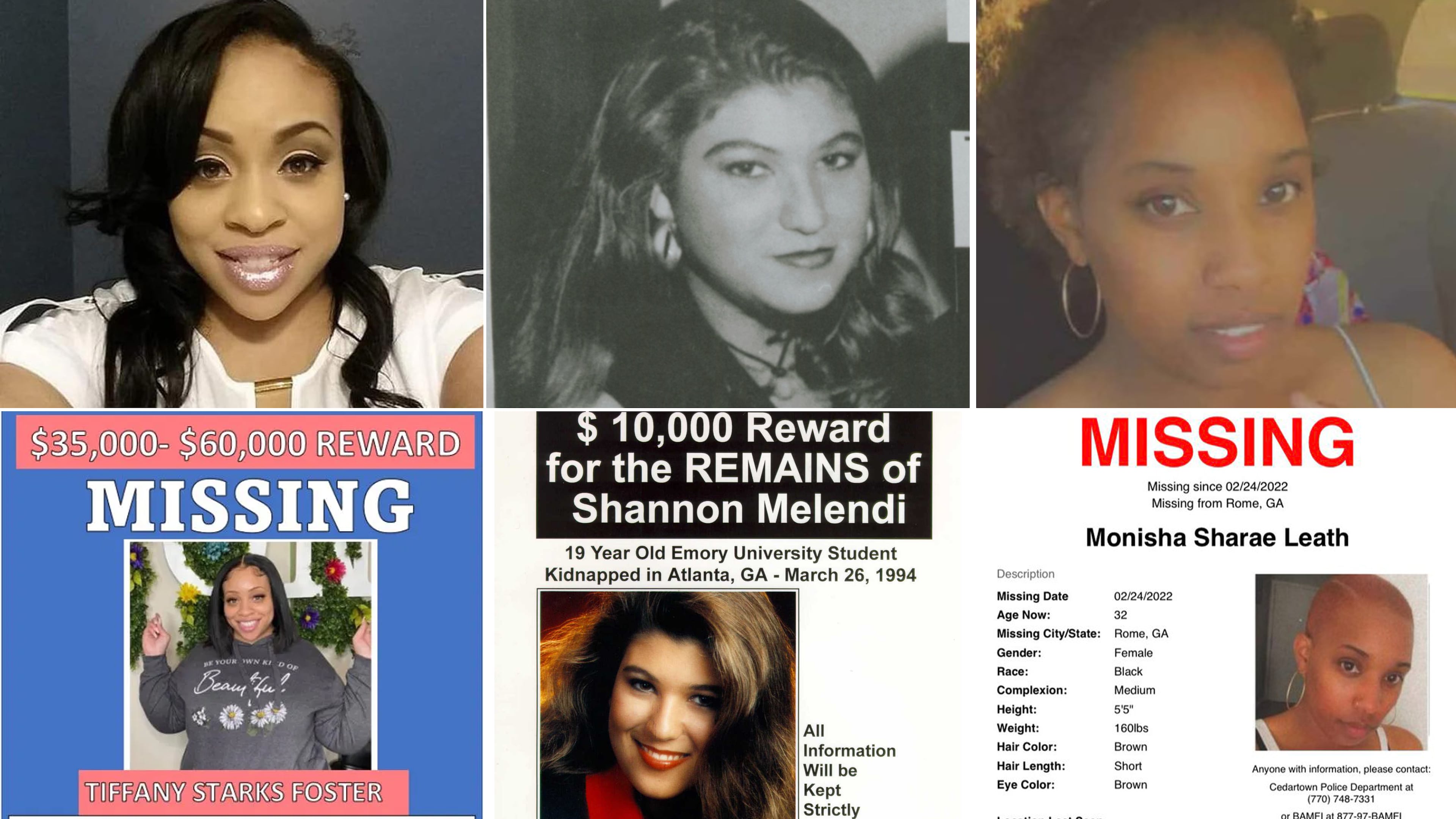

While Tiffany Foster’s family pleaded for her safe return, Robertson pretended not to know what happened. Late last month, a Coweta County jury convicted him of Foster’s murder despite one key missing piece of evidence: her body.

Convicting killers in “no body” cases has happened a handful of times in Georgia and in every other state. In recent years, more of these cases have gone to trial, one expert says. That’s because the digital clues people leave behind — including their cellphones, tracking devices and bank cards — make it much harder for killers not to leave a trace, according to prosecutors.

Those same technological advancements also make it easier to prove a person is dead, rather than just missing, said former federal prosecutor Tad DiBiase, who tracks cases throughout the U.S. and has authored a book on the topic. He has researched more than 600 “no body” homicide trials in the country, finding that 87% end with convictions.

“These electronic trails just show a jury this is when a person stopped being alive because they did nothing after this point, and that’s very powerful evidence,” DiBiase told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Lara Todd, the chief deputy assistant district attorney for the Coweta Judicial Circuit who was part of the prosecution team, said “there was an endpoint” in Foster’s movements that showed she was no longer alive.

“In the world that we live in, it’s almost impossible to not leave a digital footprint,” Todd said.

In the majority of homicide cases, the victim’s remains are vital evidence. The manner of death, autopsy findings and DNA left behind from a killer help identify those responsible.

When a body isn’t found, it’s harder to prove there was even a death, according to prosecutors. But it isn’t impossible.

Digital clues lead to suspect

Foster, who also went by her maiden name Tiffany Starks, knew she was in danger, even telling her best friend that if anything happened, Robertson was responsible, Todd said.

“The biggest thing is showing the jury that this is not a person who just got up and walked away from their life,” Todd said. “It’s a hard thing to do.”

The same day Robertson reported Foster missing, he withdrew money using her ATM card, according to investigators. Two days later, he moved her car to a location in College Park, and later the same month he wrote a check out of Foster’s account, investigators determined.

Those clues and other digital evidence helped establish Foster’s death and led investigators to Robertson.

Stacy Beckom, now an investigator with the district attorney’s office, previously worked on the case while employed by the sheriff’s office. He said what detectives found on Robertson’s phone was crucial to the case: audio files that contained confessions of past assaults against Foster.

Beckom said Robertson deleted all of his messages, “but he didn’t realize the audio files he sent (to Foster) were still on his phone.”

Without a body, how is there proof?

The first “no body” homicide case ever prosecuted in Georgia was handled by former Gwinnett County District Attorney Danny Porter, who in 1992 secured a conviction of Charles Thomas White III for the death of Randy Beck. White was sentenced to life in prison, five years before Beck’s remains were found.

Porter said the most difficult part is proving the victim is dead beyond a reasonable doubt.

“There’s a lot more pieces of evidence that you can find and bring in that would argue to a reasonable jury that the person is dead, that they haven’t just run away,” Porter said.

Evidence from Beck’s apartment showed he lost too much blood to be alive, Porter said.

Defense attorneys usually counter by arguing the victim is just missing when a body hasn’t been located.

“The argument is the person’s not dead,” Porter said. “They’re somewhere out there. They just don’t want to be found.”

Porter got another conviction in a “no body” case in 1993. A jury decided Wanda McIlwain was guilty of beating her boyfriend, George Fininis, to death with a baseball bat.

Investigators proved Fininis was dead after picking up his mattress and “literally the blood ran out of it like a sponge,” Porter said.

‘No body’ cases can be hit or miss

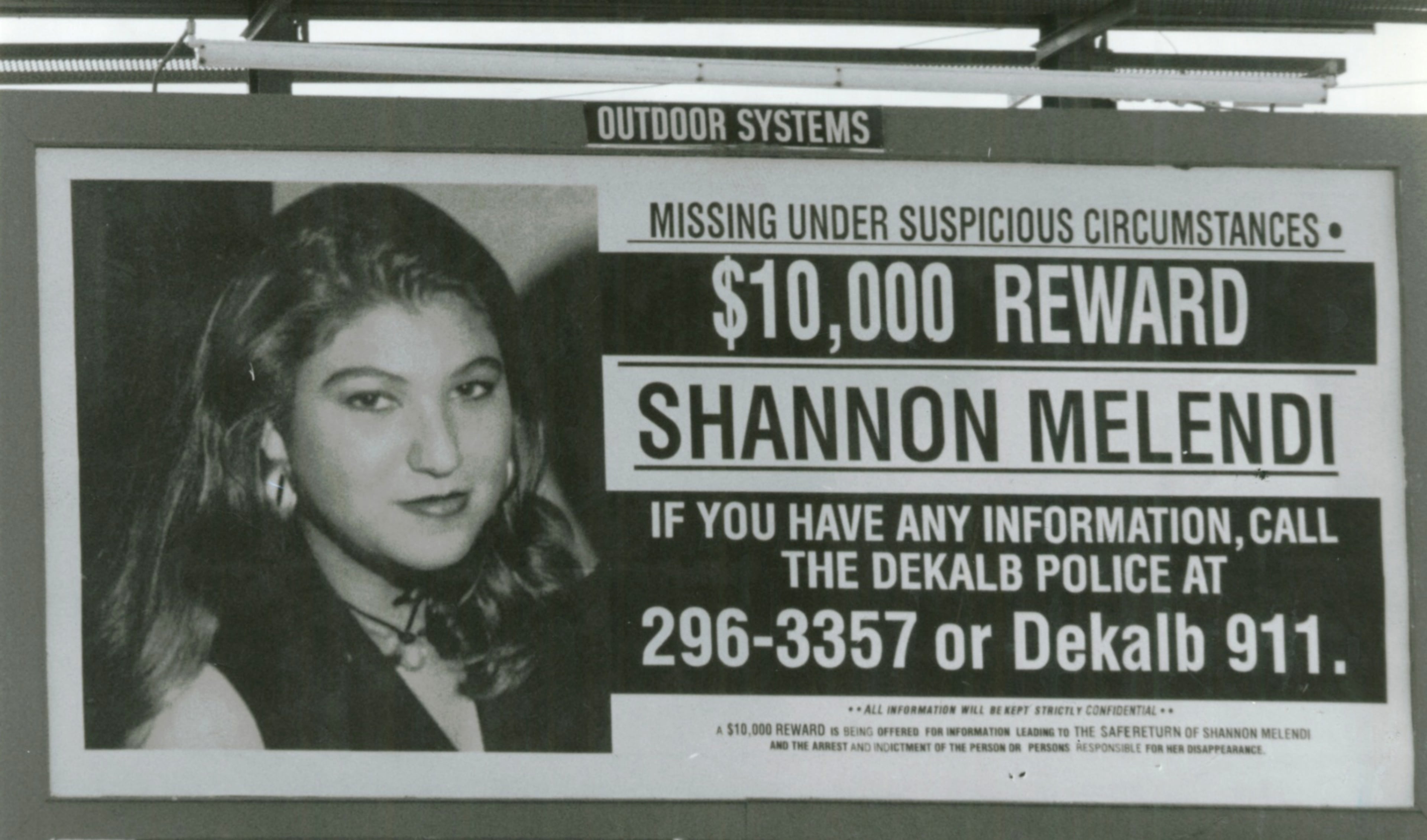

In a high-profile metro Atlanta case, Emory University student Shannon Melendi was reported missing in March 1994 when she didn’t return to her job at a softball park after lunch.

Melendi was 19, and her disappearance made national headlines. Her car was found with the keys still inside, proving she hadn’t tried to leave on her own.

Investigators eventually determined a former umpire, Colvin “Butch” Hinton III, was responsible for her disappearance and death.

Ten days after he killed Melendi, Hinton drove to a pay phone and made an anonymous call to Emory, claiming he had her. But Hinton left behind a ring he had taken from Melendi. The wrapping he put on the ring contained metal particles believed to be from Hinton’s workplace, experts determined.

The jury, convinced that Melendi had been murdered, convicted Hinton in September 2005. He was sentenced to life in prison. Less than a year later, he confessed to kidnapping, raping and murdering Melendi, but her remains were never found.

But not all cases without a body end in murder convictions. In one of Georgia’s most high-profile missing person cases, a former beauty queen vanished from her Ocilla home in October 2005.

Family and friends of Tara Grinstead said the popular Irwin County High School teacher would not have left without letting anyone know. Blood was found in her bedroom, a latex glove was located in the front yard and her car was parked outside — all signs that she didn’t just disappear. But the case went cold.

Investigators later uncovered that at least one of her former students was responsible for killing Grinstead and burning her body so her remains couldn’t be identified. However, there was no murder conviction. Ryan Duke was charged with murder, but he and Bo Dukes were both convicted of lesser charges.

‘Test the system like no others’

The majority of “no body” homicide cases involve domestic violence, DiBiase said.

In the Coweta case, there was a history of Robertson being violent toward Foster, according to investigators. Like other homicide cases where a body isn’t located, it began as a missing person investigation.

In August 2023, more than two years after Foster was reported missing, Robertson was charged with murder. He had already been accused of other crimes against her, police said.

“There was really never any question that he had done something,” Beckom said. “There was nothing to support the idea that she had run off. None of that ever made sense.”

A jury convicted Robertson on all charges, including murder, kidnapping, aggravated assault, rape, theft and concealing a death. He will spend the rest of his life in prison.

Roberta Robinson, Robertson’s attorney, said these types of cases “test the system like no others.” She emphasized to the jury to focus on evidence rather than “assumptions, speculation or sympathy.”

“You want to make sure the jury is not filling in the blanks of a ‘no body’ case with emotion, rather than what the law requires, which is proof beyond a reasonable doubt,” she said.

The jurors were ultimately persuaded by the prosecution’s evidence against Robertson, but they were not convinced his co-defendant, Jeremy Walker, played a role in Foster’s death. He was found guilty of theft by taking, but acquitted on the charge of concealing a death and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

When “no body” cases end, the search for the victim continues, along with the quest to bring closure to the family.

It’s frustrating, Todd said, that Robertson won’t tell anyone what he did to Foster and where he left her. Foster had feared he would hurt her before losing her life.

“That’s the last piece of control he’ll have over her,” Todd said.