‘Fish wrapper’: The AJC’s complicated relationship with Georgia’s political class

Lester Maddox never accused The Atlanta Journal-Constitution of “fake news.” His insults were far more colorful.

The governor banned sales of the then-separate Journal and Constitution newspapers on state property in 1970 and called them the “lowest, yellowest, crookedest, most dishonest journalism.” Then he threatened to throw their ubiquitous boxes into a nearby incinerator.

Powerful Georgia politicians warring with the press is nothing new. What’s changed over the decades is how the wars are waged.

As the AJC sunsets its print edition, we’re looking back at the complicated love-hate relationship between Georgia’s political class and its dominant newspaper.

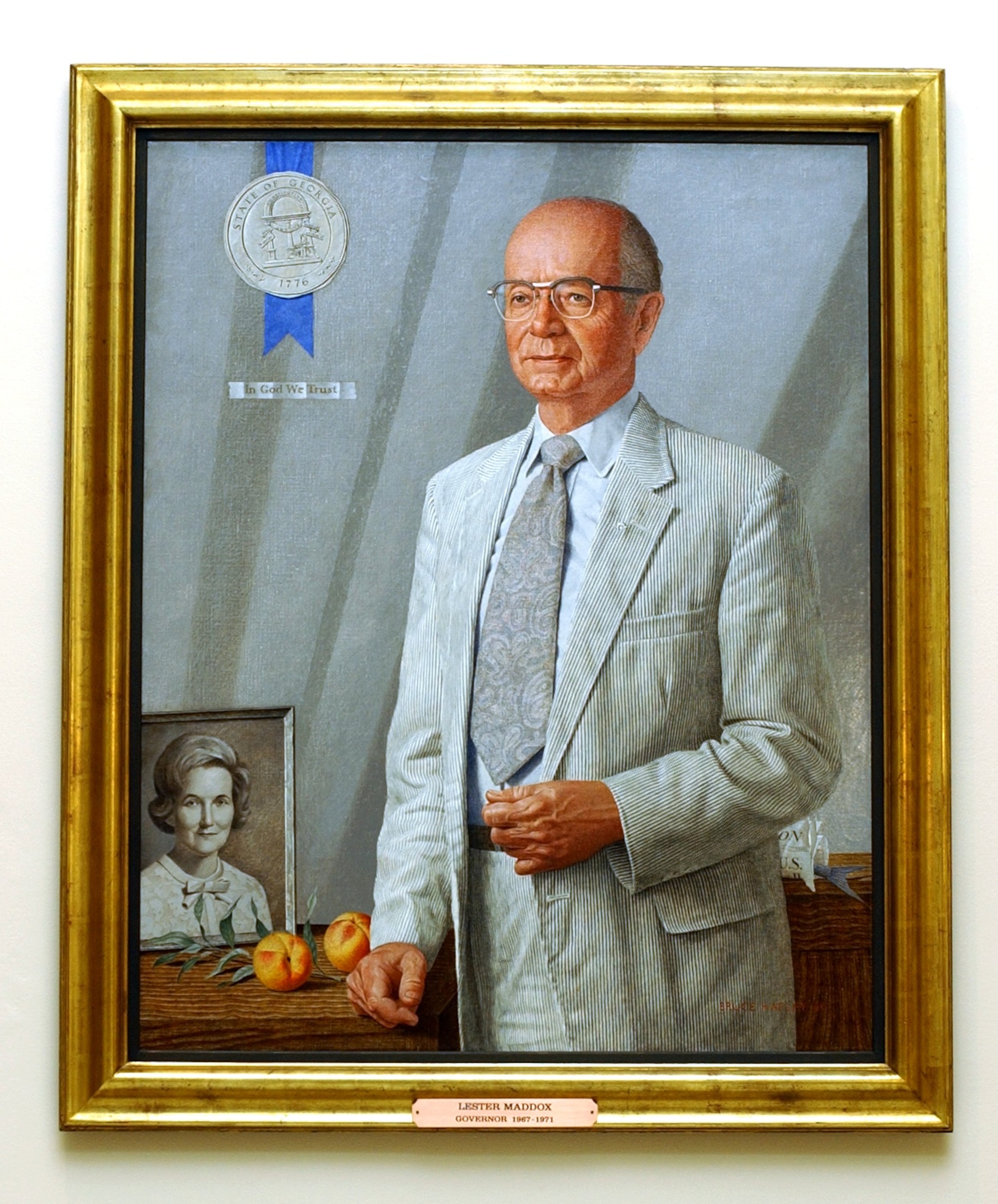

Our headline comes from Maddox himself, whose official portrait in the Capitol features a mullet draped in the newspaper he deemed a “fish wrapper.” But let’s start a bit further back.

‘Those lyin’ papers’

On the stump in the 1930s and 1940s, Gov. Eugene Talmadge turned his feud with the Constitution and editor Ralph McGill into a rallying cry. At campaign stops, a supporter would shout the line Talmadge was waiting for:

“Tell ’em about those lyin’ Atlanta newspapers, Gene!”

The crowd roared as Talmadge launched into a familiar screed that often singled out McGill, whose editorials challenged the segregationist narratives that shaped Southern politics.

McGill believed newspapers had an obligation to confront injustice and racial intolerance, and Talmadge personified everything he considered dangerous about Southern demagoguery.

His columns eviscerated the governor’s race-baiting, while Talmadge fired back from the stump with blistering attacks on the Constitution and its editor, “Rastus McGill.”

The feud ended only when Talmadge died in 1946, but it helped firm up the template for political warfare with the Atlanta press for decades to come.

The Maddox war

Maddox long maligned the “Atlanta papers,” The Atlanta Constitution and The Atlanta Journal, but the battle really blew up when the Constitution called the governor’s proposed 1970 legislative session to overhaul Georgia’s bond financing “an act of absurdity bordering on idiocy.”

An incensed Maddox ordered the Journal and Constitution vending boxes removed from state property, and when the head of the state building authority refused, Maddox threatened to send in state troopers to remove the machines.

Soon Maddox began picketing the AJC’s Forsyth Street offices, telling reporters he would protest “every time I get a chance.”

Maddox backed off his special session and lifted the paper ban by the end of that month. He declared, somewhat begrudgingly, that the newspapers had treated the controversy “about as fair as anything I’ve ever seen.”

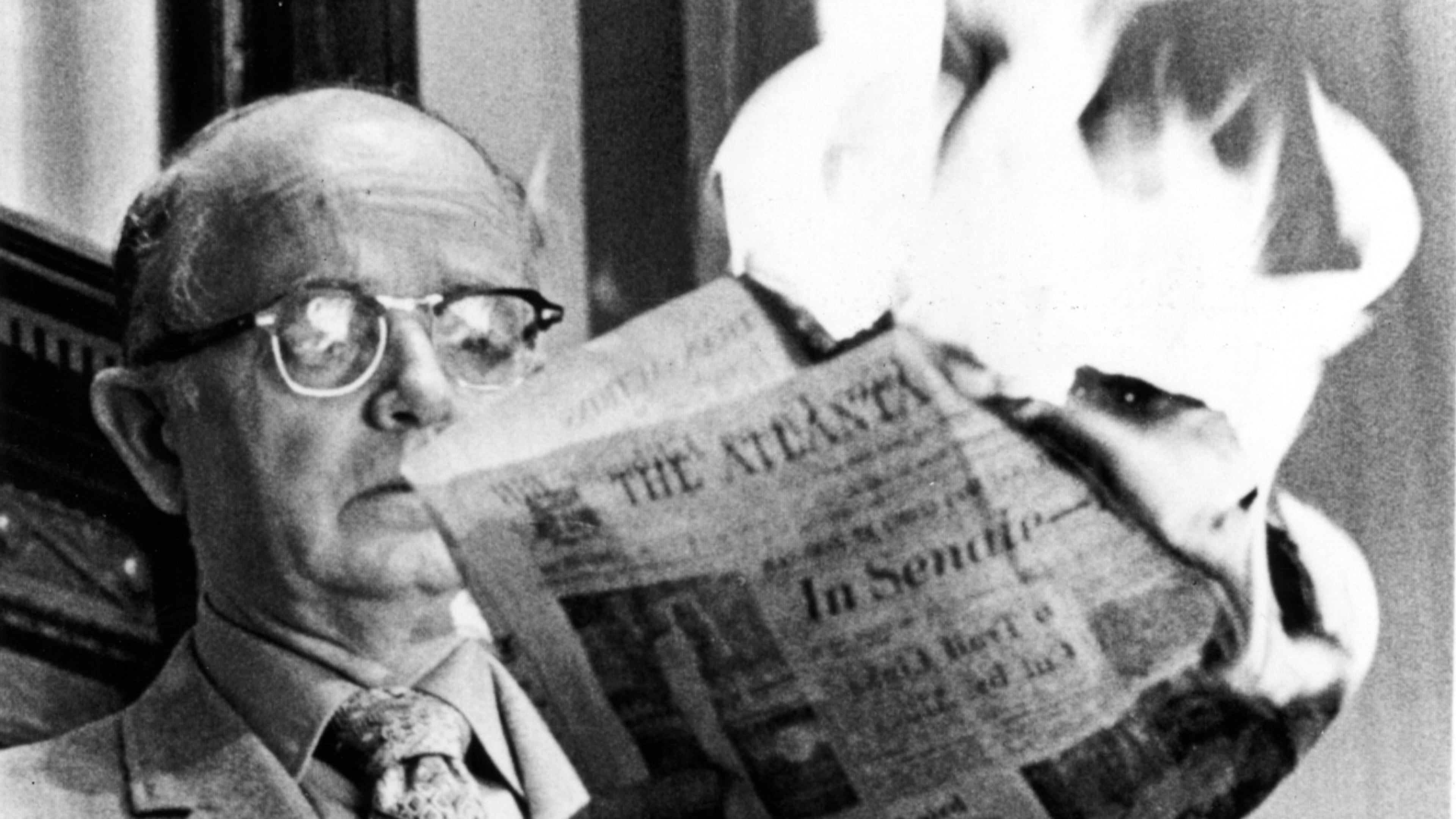

The truce didn’t last. In March 1971, now the lieutenant governor, Maddox burned a copy of The Atlanta Constitution on the Senate floor.

Then-state Sen. Jimmy Carter, already a Democratic candidate for governor, wasn’t sure he’d remove vending machines if elected — but he didn’t hide his irritation either:

“I get awfully mad at the Atlanta newspapers.”

Friction and necessity

Though Carter often clashed with the Atlanta papers, his political career might never have started without them.

When he first ran for a Georgia Senate seat from his southwest Georgia home of Plains in 1962, he lost the initial count in the Democratic primary to Homer Moore and returned home “mad as hell,” Carter wrote in his memoir.

But the numbers didn’t add up. Journal reporters helped uncover ballot boxes stuffed with wads of fraudulent votes arranged in alphabetical order, orchestrated by the local Democratic boss. Cartoons in the Journal showed graveyard precincts with caskets thrown open and their skeletal “voters” casting ballots.

Amid the pressure, a judge ordered a new election, and Carter won by more than 800 votes.

It was the biggest victory of his young political career, and it came in part because Atlanta journalists took on a powerful rural machine.

When Carter launched his presidential bid in 1974, the Constitution greeted the one-term governor’s announcement with a skeptical headline: “Jimmy Who Is Running For What!?”

Carter turned the slight into part of his outsider identity, joking that even his hometown paper couldn’t believe he was running for president.

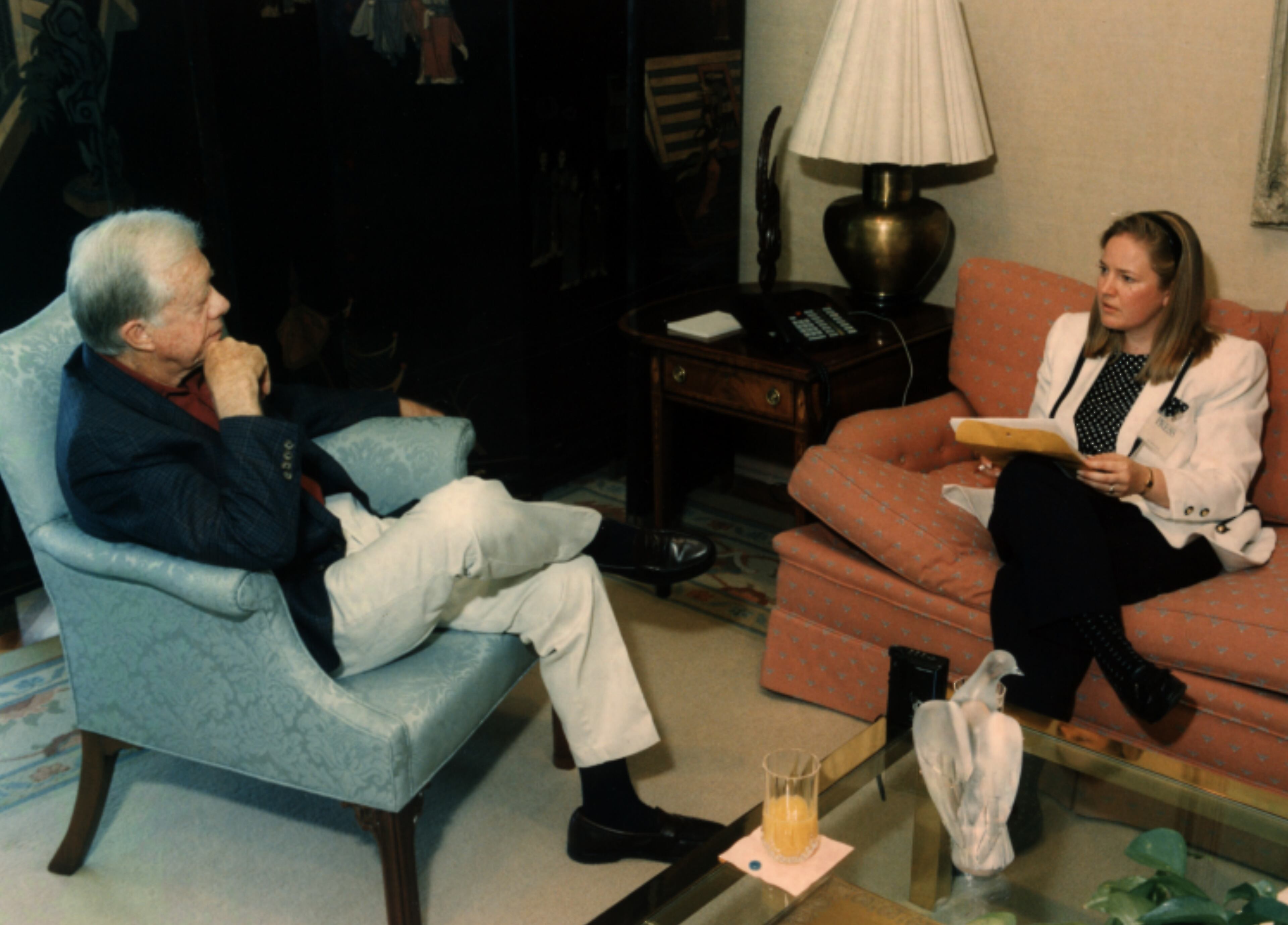

Long after he left the White House, aides and journalists alike recalled that Carter remained a devoted newspaper reader — regularly beginning his day with the AJC, even when it drove him crazy.

Sometimes, it wasn’t just the reporting that peeved politicians. Then-Gov. Zell Miller was so infuriated by the “cruel and shallow” parodies of the moonshine-drinking mountain life in the “Snuffy Smith” comic that he persuaded Atlanta Journal editors to drop the strip in 1989.

Former Gov. Roy Barnes, who won office in 1998, had his own ups and downs with the paper, from the time he served in the Georgia Legislature, when Celestine Sibley covered the chambers, to his final days as governor.

“I had a good relationship with the press. But if I didn’t like something, I was not one of those to sit around and brood,” he said of the AJC reporters who covered him. “I would call you up and tell you what I thought you got wrong and chew you out. But after that, it was over.”

Barnes recalled having just such a conversation with James Salzer, a former AJC government reporter who scrutinized Barnes’ budgets more closely than many legislators. When the governor told Salzer he’d read the wrong chart for his story, the reporter stood his ground.

“So I called him over and I chewed him out, but that was the end of it. And Salzer is still one of my favorite people,” Barnes said with a chuckle. “It’s that give-and-take.”

Former U.S. Sen. Wyche Fowler was covered by both newspapers as far back as his high school basketball days, when a young Reg Murphy, who would later become the Constitution’s editor, chronicled the Northside High School team.

He credits the paper’s extensive coverage of his time on the Atlanta City Council with helping him get elected to the U.S. House and later the U.S. Senate.

“It was just exhaustive,” he said of the City Hall coverage. “The Journal had the phrase, ‘Covers Dixie like the dew,’ but both of them did that.”

Red Georgia, the same old fights

The state’s transformation from Democratic stronghold to Republican haven in the 2000s brought a new cast of leaders — and a new set of collisions with the AJC over tough coverage.

Sonny Perdue, the first GOP governor of Georgia since Reconstruction, often bristled at the paper’s scrutiny. The tempestuous Republican lashed out over stories on his agenda, his private land deals and a string of ethics complaints.

But he also leaned on the AJC when the moment called for it. Near the end of his second term, the governor went to the newspaper’s offices after ordering an investigation into the Atlanta Public Schools cheating scandal uncovered by its reporters.

There was good reason for that.

“Whether it was in suburban Chattanooga or Valdosta, you’d find an AJC box and readers,” University of Georgia political scientist Charles Bullock said. “And every politician recognized that.”

His successor, Gov. Nathan Deal, found himself under equally intense scrutiny. In 2013, after the AJC reported on a long-running ethics complaint, he hastily called a Capitol news conference to lament the “decline” of the AJC — then, with the faintest grin, reached for Maddox’s favorite insult:

“If they continue that downward spiral as it relates to every issue of major importance they pretty well are going to descend to the level where they can’t even claim to be a fish wrapper.”

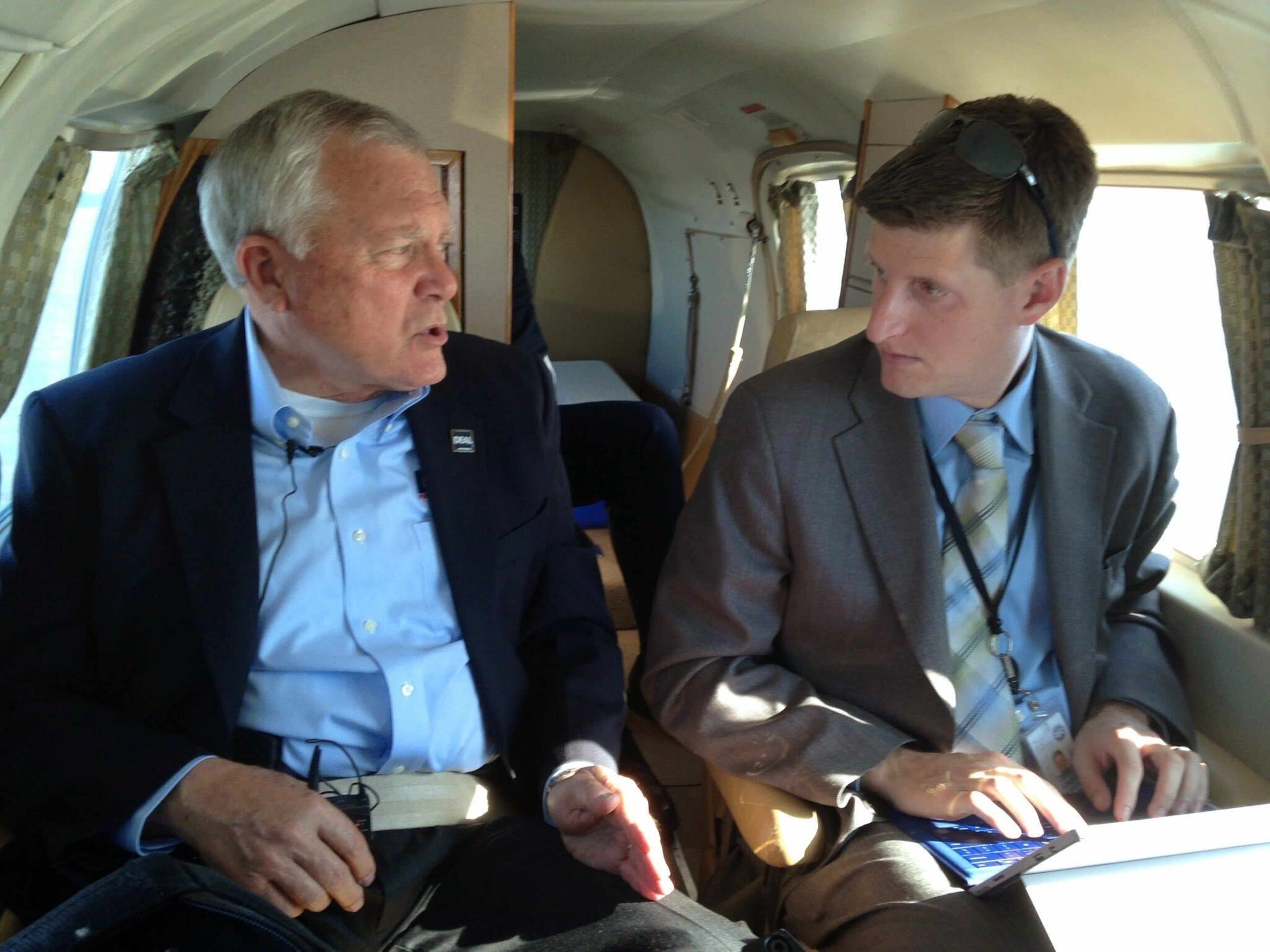

Yet Deal’s public irritation masked a more nuanced relationship. He was remarkably accessible, offering unusually candid insights that sometimes made his staff cringe. He even allowed the AJC unfettered access to his campaign in the final days of his reelection bid.

Deal could complain about the AJC in one breath and then invite a reporter to ride shotgun on a barnstorming flight the next — a reminder that he understood the value of engaging with the press rather than shunning it.

“We knew y’all were trying to do your job,” Deal said in an interview. “We may not have always agreed with the point of view that you expressed, but I had a respect for what you were trying to do, which was to inform the public.”

Reed’s rumble

The feuding extended beyond state leaders.

One of the testiest relationships came with Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed, a popular pugilist never afraid to go to war with the newspaper that described him as “hard-headed, hard-charging and a bully.”

He regularly accused the AJC of unfairness, at times issuing formal statements and social media broadsides attacking its coverage and using news conferences to rebut stories line by line.

In one memorable moment, Reed responded to records requests from the press by releasing more than 1.4 million paper documents related to an ongoing bribery investigation, holding a news conference proclaiming his transparency in front of a 6-foot wall of boxes. The AJC and Channel 2 later sued the city for violations of the Georgia Open Records Act, some of which occurred during Reed’s tenure.

Reed said in an interview he felt the newspaper had an “anti-Atlanta bias” dating back to his days in the state Legislature, and he was more than willing to fight what he viewed as a flawed narrative when he was in City Hall.

“I’m a huge fan of boxing, and I think some of the back-and-forth is good for the city because it helped inform the public opinion,” Reed said. “I enjoyed high approval ratings, and I think it’s because if you won’t fight for yourself, you won’t fight for the people in your city.”

But he also credited the newspaper’s in-depth reporting with helping illuminate some of the major policy initiatives that shaped his two terms as mayor, including a 2011 pension overhaul and the thorny battle over the new Mercedes-Benz Stadium.

“As tough a time as I had dealing with the AJC, I always took it as part of the job,” he said. “And I knew at the end of the day, if you want to be a consequential mayor, that was a major part of it.”

Near the end of his term, the bribery probe netted several guilty pleas. Reed was never accused of wrongdoing, but the tensions with the newspaper grew worse amid the scrutiny.

Reed opened his final address as mayor to the Atlanta Press Club in 2017 with a conciliatory nod to the media. “Even members of the press need a hug” with President Donald Trump in power, he said, before offering prescient advice to the reporters in earshot.

“I’m not going to go Trump on you, because you’re not fake news. You’re news. You are valuable. You are essential. But you’re entering in a world where you’re going to get it as aggressively as you’re giving it.”

The modern echo

At his gubernatorial campaign kickoff earlier this year, Republican Lt. Gov. Burt Jones invoked the late columnist Lewis Grizzard as “probably the last good writer that AJC had.”

“He’d be proud of his Dawgs and ashamed of everything else.”

It was a modern echo of the old Talmadge prompt. The backdrop may have changed, but the winking resentment sure felt familiar.

In the Trump era, politicians still regularly butt heads with the newspaper over its coverage, but now it happens on social media, at events and sometimes right from the stage of the president’s rallies.

It doesn’t stop there. Gov. Brian Kemp routinely rails against what the AJC has or hasn’t reported. Democratic leaders gladly amplify stories about MAGA-driven rifts but often bristle at coverage of their own frictions and failures.

Barnes, for one, sees the current attacks on fact-based journalism as a dangerous road to go down.

“I am very concerned about the press, our place in democracy and how we’re losing what truth is,” he said.

It’s just the latest chapter in a familiar saga. Through the decades, the AJC has been a watchdog, a megaphone, a foil, a punching bag and an unwelcome mirror for politicians who mess up.

Georgia politicians have picketed the newspaper, banned it, burned it, brandished it under the Gold Dome and on the floor of Congress, embraced it when convenient and scorched it when not.

But they’ve never ignored it.

As Georgia politics enters a faster and even more fragmented age, the AJC’s relationship with its most powerful subjects remains as complicated and as essential as ever.

Politicians may have called it a fish wrapper. But they keep reading it.

And, more importantly, so do Georgia voters.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the year Roy Barnes won the governor’s office.