Dr. William (Bill) H. Foege, Atlanta global public health giant, dies at 89

CNN medical journalist Sanjay Gupta asked Atlanta’s Dr. William (Bill) H. Foege during a 2018 awards ceremony what he thought about some people crediting him with saving more lives than anyone in history.

“I ignore it,” Foege replied. “Nothing is done by an individual. Everything is done by coalitions.”

It was a typical answer from Foege, who lived much of his life in Atlanta, to push credit to others for saving millions of lives globally through disease control and elimination. That humility was one of the reasons for his success, allowing him to build trusting relationships with people and agencies across the world, according to those who worked with him. It is also a reason why people who are alive because of his work may have never heard his name.

Foege is credited with spearheading the global effort that eradicated smallpox, which killed an estimated 300 million people between 1900 and its elimination in the 1970s. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012.

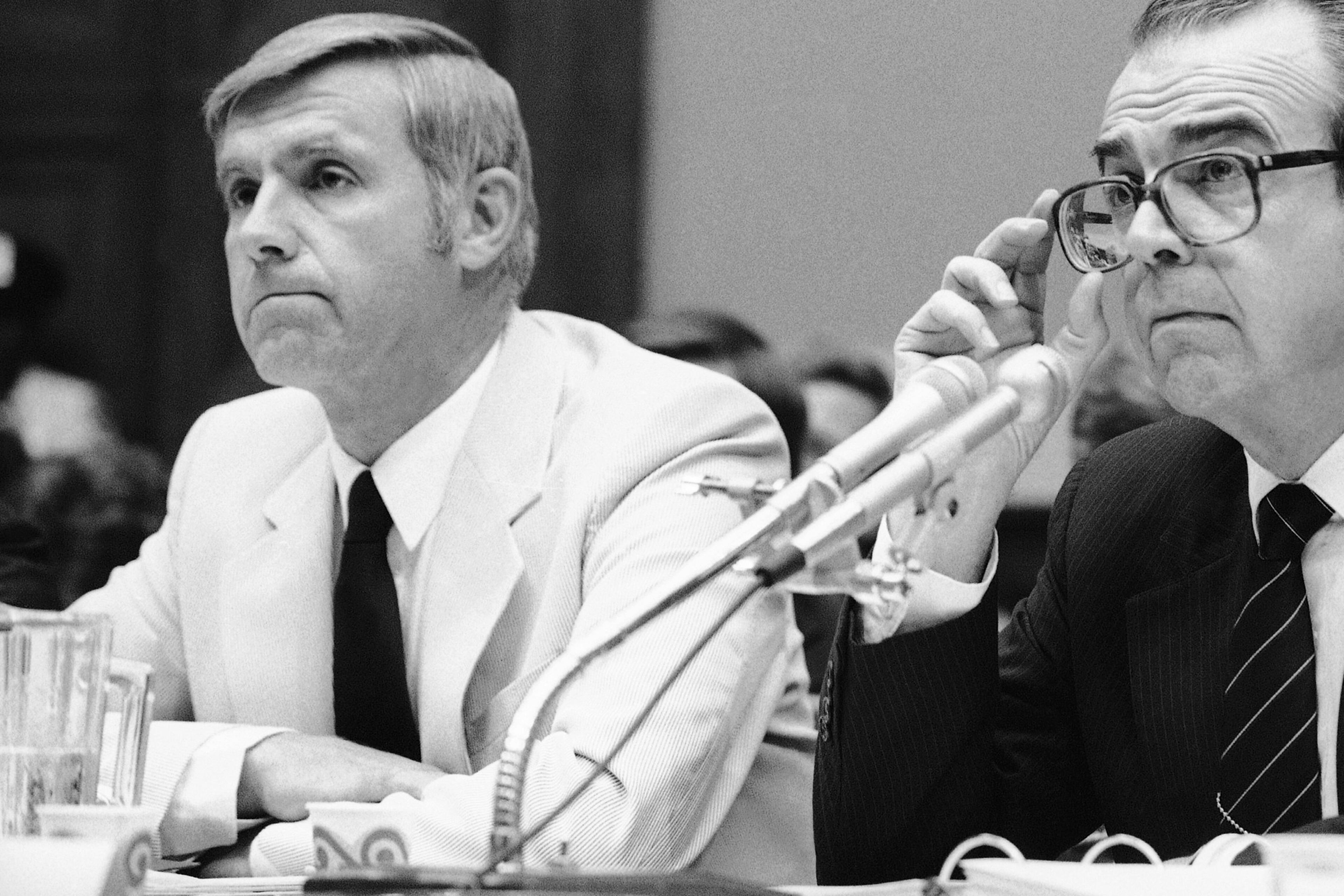

He directed global disease fighting and eradication programs at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which he headed from 1977 to 1983. He led similar efforts at the Carter Center and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation over a decadeslong career and helped clinch an agreement that significantly boosted childhood vaccinations across the planet.

Foege died Saturday in Atlanta at the age of 89, according to the Decatur-based Task Force for Global Health, which Foege co-founded in 1984.

“Dr. Foege is justly regarded around the world as a singular public health hero, whose achievements are monumental,” Patrick O’Carroll, the nonprofit’s CEO, wrote in a statement that also described Foege as “an essentially humble man.”

Longtime colleague Dr. Mark Rosenberg, who played a role in the smallpox campaign and later led the Task Force for Global Health, said Foege was in India in the late 1970s overseeing the elimination of the last cases of smallpox when Foege called his boss at the CDC in Atlanta and said he was coming home.

“And his boss said, ‘Absolutely not! Don’t you see?’ In a few months smallpox would be eradicated from India, and this was going to be the biggest achievement in global health ever,” Rosenberg recalled.

Foege told his boss: If I am here when it’s eradicated, all the attention will be on foreigners. This is what the Indian people did, and they deserve the credit. I am going home.

And he did.

“He said, credit is infinitely divisible. You can always give it away,” Rosenberg said.

Inspired as teen by Albert Schweitzer

The world got lucky when 15-year-old Bill Foege was bedridden for weeks in a body cast because of a hip problem.

He was born March 12, 1936, in Decorah, Iowa, the son of a Lutheran minister. The family moved to a small Washington state community while he was still a teenager.

Foege told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2015 that while in a body cast he had little to do but read, including a book by Albert Schweitzer, the medical missionary, theologian and humanitarian. That inspirational spark grew into the beacon that lit his life’s way. He also had an uncle who was a medical missionary.

Foege attended medical school at the University of Washington, where he delved into his interest in disease control, then worked in the U.S. for a few years. He earned a master’s degree in public health at Harvard in 1965 and went to work in the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service and its ongoing effort to eradicate smallpox in West and Central Africa. Within a few years, he was named the chief of the Smallpox Eradication Program.

Campaign to eradicate smallpox

He was in Nigeria when civil war erupted in the late 1960s. He had his young family evacuated, but he stayed, in spite of the danger, and was credited with rescuing a fellow health worker held at gunpoint by a 13-year-old rebel. He himself was held twice in detention, finally escaping to Ghana, crossing the Niger River in a canoe.

Foege, whose dry wit was as well known as his intelligence, told Tom Griffin, editor of the University of Washington’s “Columns” magazine, “I remember thinking, ‘Medical school wasn’t ever this hard.’”

It was while working in Africa that he developed the methodology to corral and eliminate smallpox. Modern vaccines were in widespread use by the 1960s, and the last U.S. case was reported in 1949, according to the CDC. But administering hundreds of millions of doses to large enough swaths of poor, undeveloped countries had proved elusive.

In Africa, Foege built a communications and action network of medical missions, local health centers and government officials that began seeking out and reporting cases quickly. Medical teams sprinted in to prevent spread by quarantining and vaccinating a ring of people who had been near the infected person. That allowed health workers to stem the spread with a moderate number of vaccines.

He applied the same method while heading the CDC’s efforts and helped spread the program. By the early 1970s, smallpox was cornered in South Asia and the Horn of Africa. The World Health Organization certified it as eradicated in 1980.

‘He did do spectacular things’

Foege returned home to direct and reorganize the CDC, work for the Carter Center, Emory University’s medical school, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and other organizations.

“He did do spectacular things,” Rosenberg said.

He co-founded the Task Force for Child Survival and Development, now called the Task Force for Global Health. The metro Atlanta nonprofit has worked in more than 150 countries to eliminate diseases, ensure access to vaccines and essential medicines and strengthen health systems.

As of a few years ago, it had administered more than $950 million in medicine and vaccines that treat people for intestinal worms, river blindness, measles, leprosy, trachoma (the world’s leading infectious cause of blindness), elephantiasis and a host of other diseases. It has helped eliminate at least one tropical disease from 50 countries and seen polio cases drop 99%.

Since 1990, the world’s under-5 mortality rate has dropped 59%, according to the World Health Organization’s statistics, with the decline attributed to vaccines and better care.

Foege also is credited with getting the WHO and UNICEF to break a political impasse. The two international agencies were at odds in 1984 over who would run a world vaccination program for children and how it would operate. The two heads of the organizations approached Foege.

“I felt like a therapist,” Foege recalled in a talk at the 2018 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Decatur Book Festival. “They said, ‘We have such big egos, we have trouble getting along.’”

But they agreed that Foege was a person who could head it up — as long as they both got credit and if Foege would promise to keep a lower profile than both of them. It was an easy choice for him.

“Six years after we started, where (world) immunizations rates had been 15% or 20%, it was announced that 80% of the children in the world had now received their first vaccines,” he said.

Though Foege was content to operate in the shadows, he was unafraid to face others and speak frankly about human needs, responsibility and morality. That was part of what made him a hero to so many in the health community.

He was asked in 2020 by his grandson, Max Morell-Foege, what more he wished he would have done.

“I would have spent more time on poverty reduction, because I see poverty as the slavery of today. That all of us are subsidized by people who are poorer than we are. And that we get clothes and food and travel and everything cheaper because people are working at low wages in this country and abroad, and it’s just not right. And we should be so ashamed, so embarrassed that we’re now the plantation owners and we don’t want to change things,” he answered.

Survivors, according to The New York Times, include his wife, Paula (Ristad) Foege; two sons, Robert and Michael; three sisters, Mildred Toepel, Annette Stixrud and Carolyn Hellberg; four grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.