Locked up as teens: Lawsuit says Georgia gave them no path to parole

As a teenager, Janice Buttrum joined her husband in the murder of a young woman at a North Georgia motel.

Over the last 44 years, Buttrum has been in prison, trying to prove that she’s a different person from her adolescent self — and that she deserves a chance for freedom. Five times, the state has refused, saying that given the crime, she must do more time.

Two federal lawsuits are challenging the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles, claiming that its parole process — specifically with regards to people imprisoned as teenagers — violates seminal U.S. Supreme Court rulings.

If successful, the lawsuits could impact Buttrum, and possibly with future legal actions, the 500 others in Georgia prisons who, like her, were sentenced as teenagers to life with parole.

“The point of these cases is to make sure that Georgia follows the law by recognizing that juvenile offenders are different and by giving them a fair opportunity to prove that they’ve matured and don’t pose the same risk to society now that they’re adults — or, more accurately, old people,” said Ronan Doherty, an attorney with Bondurant, Mixson & Elmore who has voluntarily taken on the cases.

Over the last two- decades the U.S. Supreme Court has issued several rulings — Miller v. Alabama; Montgomery v. Louisiana; Graham v. Florida; Roper v. Simmons — on the punishment of people under 18 years old. The decisions cite brain science, which shows young people are impulsive, prone to peer pressure and environmental factors, and, most importantly, that they are well-equipped for rehabilitation.

Young people, according to the high court, must be sentenced differently. Specifically: Courts cannot sentence kids to die in prison — life without parole — except in the rare case that children are “irreparably corrupt.”

Even when they commit heinous crimes, they should get a second look as they mature; they need, wrote the justices, a “meaningful opportunity for release.”

Yet despite these rulings, many in Georgia are stuck in limbo, beholden to an opaque and unaccountable body — the parole board — according to the lawsuits.

The other plaintiff is David Moore, who, like Buttrum, entered prison as a teenager. Moore was sentenced to life with parole in 1987 for his role in an armed robbery that left a man paralyzed. He has been denied parole eight times since he first became eligible in 1994.

The suits argue that by basing its parole denial on the original crime — a static factor — with no consideration of change or youth, the board is essentially issuing sentences of de facto life without parole. This is a violation, according to the suit, of the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits cruel and usual punishment.

They also accuse the board of being in violation of the 14th Amendment — the guarantee of due process of law — as there are no stated guidelines for how the board decides whether to give parole to people serving life sentences.

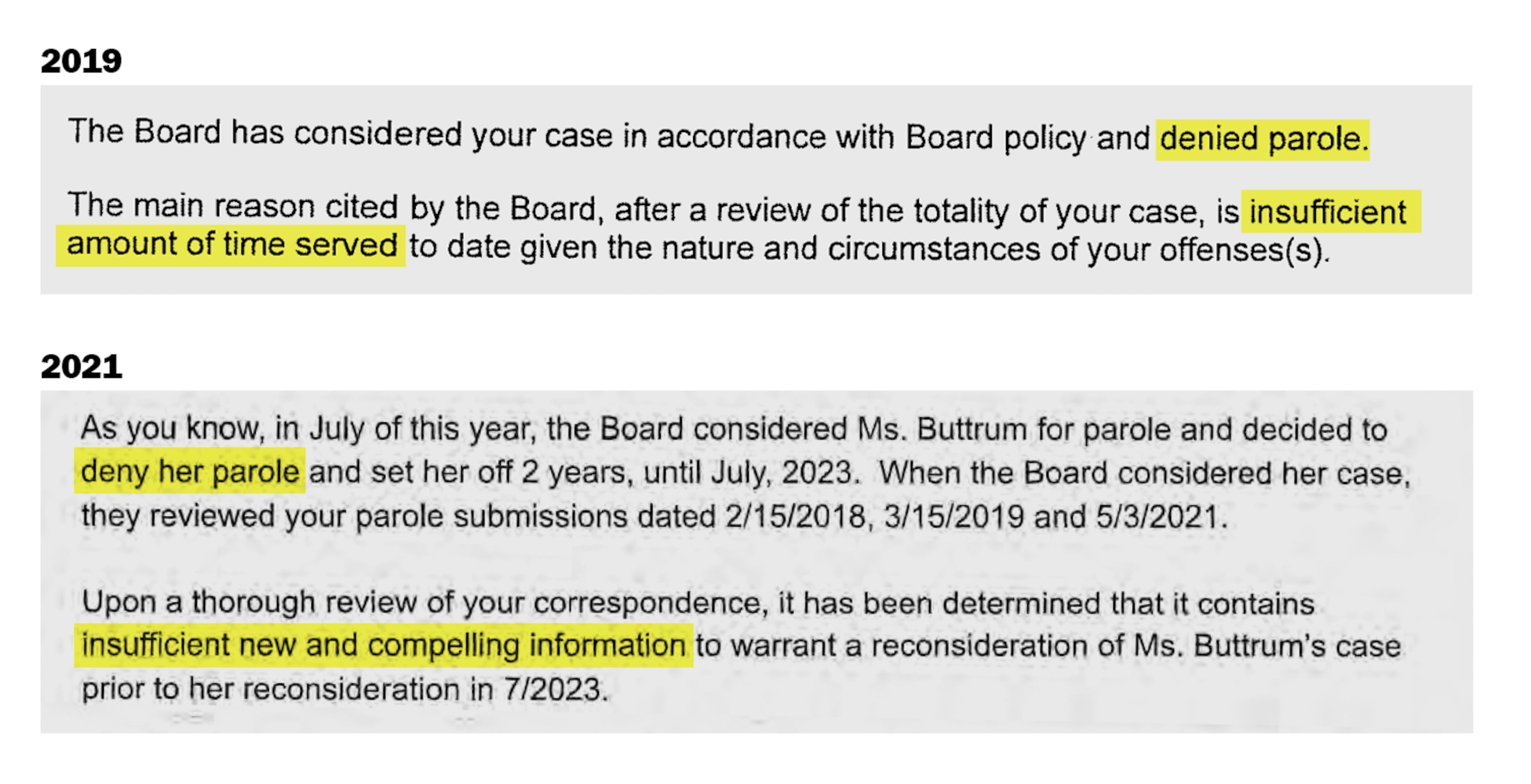

The lack of a road map to parole, the suits allege, is particularly pertinent when it comes to people convicted and sentenced as children. The suits note that denial letters give no path for a different outcome, simply stating people are being denied due to the nature of the crime and not enough time served.

Buttrum’s suit notes that when she requested documents showing whether she was being assessed differently given that her crime was committed as a teenager, the board said there were no such documents.

Steve Hayes, a spokesperson for the state parole board, declined to comment on the suits but issued a statement on the board’s handling of these cases:

“The Board provides meaningful consideration to all parole-eligible offenders. The Board uses its discretion authorized by the Georgia Constitution to make release decisions.”

He did not respond to questions on how the parole board reviews people serving life sentences, or how they make their decisions.

Quiet and settled

The details of Buttrum’s case are not easy.

In 1981, when Buttrum was 17, she and her 28-year-old husband, Danny Buttrum, made headlines when they were convicted of brutally killing a 19-year-old woman in a north Georgia motel. The victim was raped and sodomized and stabbed 97 times with a pocketknife.

The teen was sentenced to the death penalty.

But over the last four decades, her sentence has changed to reflect the high court’s rulings: which specifically said young people who commit crimes shouldn’t die at the hands of the state. They deserve a second look.

In 2017 a superior court judge re-sentenced her to life with the possibility of parole — a sentence that, at least on paper, gave Buttrum, now a 62-year-old great-grandmother, a path to return home.

And so, with the high court’s rulings, the judge’s new sentence, and case law seemingly on his side, in 2018 Mark Loudon-Brown, Buttrum’s parole attorney, made her case to the board.

He described the transformation his client had undergone over more than four decades.

She had taken college courses, completed 60 life development courses offered by the department of corrections and earned a spot in the Honor Dorm at Pulaski state prison due to “positive attitude and commitment to self-improvement.”

Buttrum, with salt and pepper hair who uses a walker to move around, had done one of the key things the parole board emphasizes in its mission statement, the letter pointed out: She had used the time behind bars to make a positive change.

“Ms. Buttrum,” the letter stated, “is no longer the person she was at 17-years old.”

The parole board was unmoved. Buttrum, they said, had not served enough time “given the nature and circumstances of your offenses.”

The next four times she was considered she received the same “rote denials,” according to the suit.

“It’s a murder case, it’s a former death penalty case, so, sure, it’s going to be challenging. You’re going to have to grapple with the facts of the crime,” said Loudon-Brown, an attorney with the Southern Center for Human Rights, a nonprofit public interest law firm. “But she was a child. She’s done, at this point, well over 40 years in prison, her health is not great. To me there is no penological justification to keep her in prison.”

“Or at least I haven’t heard one from the board,” he continued.

While the details of Buttrum’s case are tough to hear, they are also, according to her attorneys, not reason enough for a person who committed a crime as a teenager to be denied parole or the only issues the board should be looking at.

In addition to the capacity for rehabilitation, the high court stated that when a sentence of life without parole is to be considered, judges and juries should also consider other issues, like a young person’s home life and the circumstances of the crime, such as influence by adults.

The suit argues that the parole board also has a duty to take into consideration these details. For Buttrum it means taking into account that she co-committed the crime with a much older man, and had a horrible and abusive upbringing.

According to the suit, Buttrum married her husband when she was 15-years old. He was 26 and divorced and had documented substance abuse issues. Prior to meeting him she was in and out of the foster system, where she suffered sexual abuse. Teachers and social workers within the community all testified during court proceedings to her mistreatment.

“Janice was probably the most neglected child I’ve ever seen in my life,” a social worker with Bartow County Schools stated at a court hearing in 1981, noting that he knew that at 14 she once spent the night with two 27-year-old men “simply because they promised her a little love and affection.”

The department of corrections denied the AJC’s request to interview Buttrum.

Some insight into her state of mind, however, is seen in her application to the “honor dorm,” a special living unit for people who demonstrate good behavior, her lawyers said.

“I am quiet and settled,” she wrote on the 2011 application, later adding: “I know how to settle my problems by talking them out. I feel that I am a positive role model on how to do time.” The document noted that her last disciplinary report was in 1999.

Asked for all documents that the parole board reviewed when considering Buttrum’s parole, the board provided the AJC with 28 pages of court documents from her first trial. The file did not include anything related to Buttrum’s last 44- years in prison. Many documents, according to the board, are “confidential state secrets.”

‘A bright future, if given a chance’

Moore, who has been incarcerated since the Reagan administration, for a crime he committed at age 17.

Over the past nearly 40 years he has taken advantage of all the rehabilitative offerings the department of corrections offers. Recently he was one of 221 people selected for the state’s prisoner mentor program known as R.I.S.E (Reinforcing, Instructing, Supporting, and Empowering.)

Yet despite his evolution he has been denied parole regularly, with his most recent denial coming earlier this year.

Moore believes his denials likely have to do with the fact that in 1989, two years after he was sentenced, he was involved in a prison fight. Moore said he was attacked, and in the mayhem, another man was killed.

He got 15 years — which he has long finished serving — but assumes the fight is impacting how his parole eligibility is viewed.

The parole board would not give details on why Moore has been denied paroled. His denial letters, like Buttrum’s, simply state he is being denied due the nature of his crime and not enough time served.

Writing via his cousin, Joaquin Knight, to whom an AJC reporter sent questions, Moore, now 55, discussed the loneliness of growing old behind bars, as well as the shame he carries for his actions in his youth.

“There are absolutely no words contained in the English vocabulary capable of expressing my most genuine and sincerest regrets and apologies,” he wrote.

But these two incidents are also, he contends, not indicative of who he is today. Like Buttrum, Moore believes he is a different person from the teenager who entered the Georgia Department of Corrections nearly four decades ago.

And, he argued via a lawsuit he self-filed in March 2023, the parole board is violating his constitutional rights by not taking this into account.

While Moore’s complaint — which he filed without the aid of an attorney — was originally dismissed, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in his favor last April in a 2-1 decision, punting the case back to federal judge Amy Totenberg, who subsequently assigned Moore representation.

According to Doherty the decision to appoint an attorney to help Moore is not typical. He noted that while the appointment doesn’t say anything about the merits of the case or who’s likely to win, he does believe it suggests an acknowledgement that the case is grappling with critical and substantive case law that could impact others given life sentences as children.

“I left our first meeting struck by what a waste it is for him, his family, and even the state of Georgia and its taxpayers to have David sitting in prison all these years later,” said Doherty, noting how remarkable it was that Moore had gotten this far without any legal help.

“He impressed me as someone with a bright future, if given the chance,” he said.

A black box?

In Georgia the parole board is made up of five governor appointees who serve rolling seven-year terms. Unlike in many states, parole board members do not meet with individuals when weighing decisions, and people cannot access their “files” to see what information is being considered.

This lack of transparency is a key point of the suits and a long-standing criticism of the parole board by attorneys and advocates, who often liken the process to a “black box.”

State Board of Pardons and Paroles

Founded in 1943 and expanded to five members in 1973, when Georgia’s prison population was 9,000. (Today the prison population is roughly 50,000.)

Members serve seven-year terms. A vote of three is required to grant or deny parole.

David J. Herring, chairman (term 2018-2025): former state trooper (became chairman July 2024)

Meg Heap, vice chairman (2021-2028): former district attorney for Georgia’s Eastern Judicial Circuit

Joyette Holmes (2024-2031): former district attorney for Cobb County and former chief magistrate judge for the Cobb Judicial Circuit (special prosecutor for the Ahmaud Arbery case)

Wayne Bennett (2024-2031): former sheriff of Glynn County

Robert Markley (2025-2032): former sheriff of Morgan County

A 2014 AJC investigation documented the opaque nature of the parole board, specifically from the viewpoint of victims’ families, who at the time were not alerted when a person was paroled and released. The state subsequently passed legislation giving families and prosecutors a 90-day window to weigh in on a tentative parole.

While the legislation has been commended for giving victim’s families more insight into the process, attorneys say it has had the opposite effect for their parole-eligible clients, who can suddenly have their tentative parole revoked after 90 days.

“It’s the standard letter without further explanation,” said Michael Shapiro, an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at Georgia State University, who recently had a client who was given hope via a “tentative parole” notification only to have it revoked after the 90- days.

In addition to people not knowing why they are being denied parole, those who get parole are often left in the dark, according to Leigh Schrope, a Decatur-based attorney who represents people in the parole process.

In 2023 one of Schrope’s clients — Michael Lewis — was released from prison after 26 years after being indicted at the age of 13 for a 1997 homicide and sentenced to life with parole.

“It's the standard letter without further explanation."

According to Schrope it is unclear what finally made the board change its mind and allow Lewis, then 40, to come home.

“Even those who are granted parole often do not receive an explanation,” said Schrope. “The end result is that many are left feeling that the entire process is arbitrary.”

Others waiting

While the complaints are not class-action, an analysis of Georgia Department of Corrections data by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution helps to contextualize the allegations.

There are currently over 500 people serving life with parole sentences for crimes committed between the ages of 13 and 17 in Georgia, data shows.

The state has some of the highest numbers of young people serving life with parole sentences in the country, according to Ashley Nellis, an assistant professor at American University’s School of Public Affairs, who researches sentencing nationally.

A big part of that has to do with SB440, a 1994 law requiring children as young as 13 to be treated as adults and prosecuted in Superior Court if they were indicted for violent crimes like rape, aggravated battery, armed robbery and murder.

Buttrum is among 14 people who have served 40 or more years waiting for parole for crimes committed as children. She and Moore are among 67 people who have served over 30 years.

While over 300 people are currently eligible for a parole review, only 17 have been released in the last two and a half years ending in March 2025, according to data reviewed by the AJC. And six parole-eligible people have died while waiting during that same time-frame.

Hayes declined to comment on the data findings.

Advocates, however, say the six deaths underscore the crux of the suits: In Georgia no one is guaranteed the right to parole, but children, according to the U.S. Supreme Court, are supposed to be considered differently from adults and are not supposed to die behind bars.

“It is very concerning if people who committed crimes as children are dying in prison even if they have demonstrated the constitutionally required maturation and rehabilitation that should have entitled them to release,” said Loudon-Brown.