Progress toward Stone Mountain truth-telling exhibit a ‘positive step’

Monuments are subjective things.

They represent, as the American Historical Association put it in 2017, “a moment in the past when a public or private decision defined who would be honored in a community’s public spaces.”

Monuments are opinions, and sometimes pointed messages, writ large. They are not history in and of themselves but experiments in what’s called “collective memory.”

Confused? That’s fair.

A new, paradigm-shifting museum exhibit planned for Stone Mountain Park will attempt to explain further — while also hashing out the uncomfortable origins of the world’s largest Confederate monument.

“People have interpretations” of the history, Alan K. Sims, area president for Warner Museums, said this week. “But there’s only one truth.”

Warner was officially hired Monday for the new gig — a multimillion dollar project that involves using Stone Mountain’s existing Memorial Hall building to “tell the truth” about the park and its carving of Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee.

It had been some 19 months since the creation of such an exhibit was greenlighted and longer still since the idea was first broached by the Stone Mountain Memorial Association, the state authority tasked with overseeing the state’s most visited and most divisive attraction.

It’s projected to be yet another two years before everything’s built and open to the public.

But while progress has been slow, the significance of anything happening at all should not be undersold. And the details of the proposal now accepted by the historically change-resistant memorial association are encouraging to those that have long advocated for a more honest telling of the mountain’s story.

“It’s a major, major step forward. It just is,” DeKalb County CEO Michael Thurmond, a former memorial association board member, said. “The truth sets you free.”

‘Bold enough’

To be clear, exact content for the truth-telling exhibit is still to be developed, with input from community members and historians. Nothing specific was approved this week by the memorial association board, a point that member Ray Smith went out of his way to get on the record.

Warner, though, was hired to lead the work, a fact it may owe to its willingness to lean in.

All six of the companies that bid on the project were experienced exhibitors with impressive portfolios. But most of the proposals were far less detailed than that of the ultimate winner, at least on the static versions provided to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution: here’s stuff we’ve done before, here’s our general process, we’d love to work with you, etcetera.

Warner — a Birmingham-based firm that’s built exhibits commemorating the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, freedom riders, and Negro League baseball, among others — went ahead and laid it all out there.

Its proposal signaled that it would not shy away from speaking directly to the “truth” aspect of the mountain and the carving, referencing white Southerners’ post-Reconstruction efforts to recast the Civil War as a battle over states’ rights and how that became connected to racial segregation, Jim Crow laws and the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan atop Stone Mountain.

“Fittingly,” the proposal says, “D.W. Griffith’s 1915 landmark film, Birth of a Nation, a play on protecting Anglo-Saxon heritage, helped to inspire the formation of the new Klan and served as a catalyst for the creation of the Stone Mountain monument.”

The carving wasn’t finished the first go-round, but was picked back up decades later when, as Warner wrote, “white demagogues pledged to defy federal law and oppose the movement for civil rights.”

As envisioned, the exhibit would explore how “the collective memory created by Southerners in response to the real and imagined threats to the very foundation of Southern society, the institution of slavery, by westward expansion, a destructive war, and eventual military defeat, was fertile ground for the development of the Lost Cause movement amidst the social and economic disruptions that followed.”

It would not only lay the facts bare, but provide context, explain how things evolved and where they’re going.

“The fact that they were bold enough to go ahead and mention that, and take a stab at what they thought, was a positive,” memorial association CEO Bill Stephens said.

Sheffield Hale is president and CEO of the Atlanta History Center, which has documented Stone Mountain’s history but is not currently involved in the exhibit process. Hale called the mountain “the only monument in the country that has a built-in museum at its base that has the sufficient space to tell its entire story.”

“If it’s done right, I would say it’s a necessary, but not necessarily sufficient, step,” Hale said. “Phase I is to tell the truth.”

‘Adding to the story’

Stone Mountain Park is, of course, still mandated by Georgia law to serve as “an appropriate and suitable memorial for the Confederacy.”

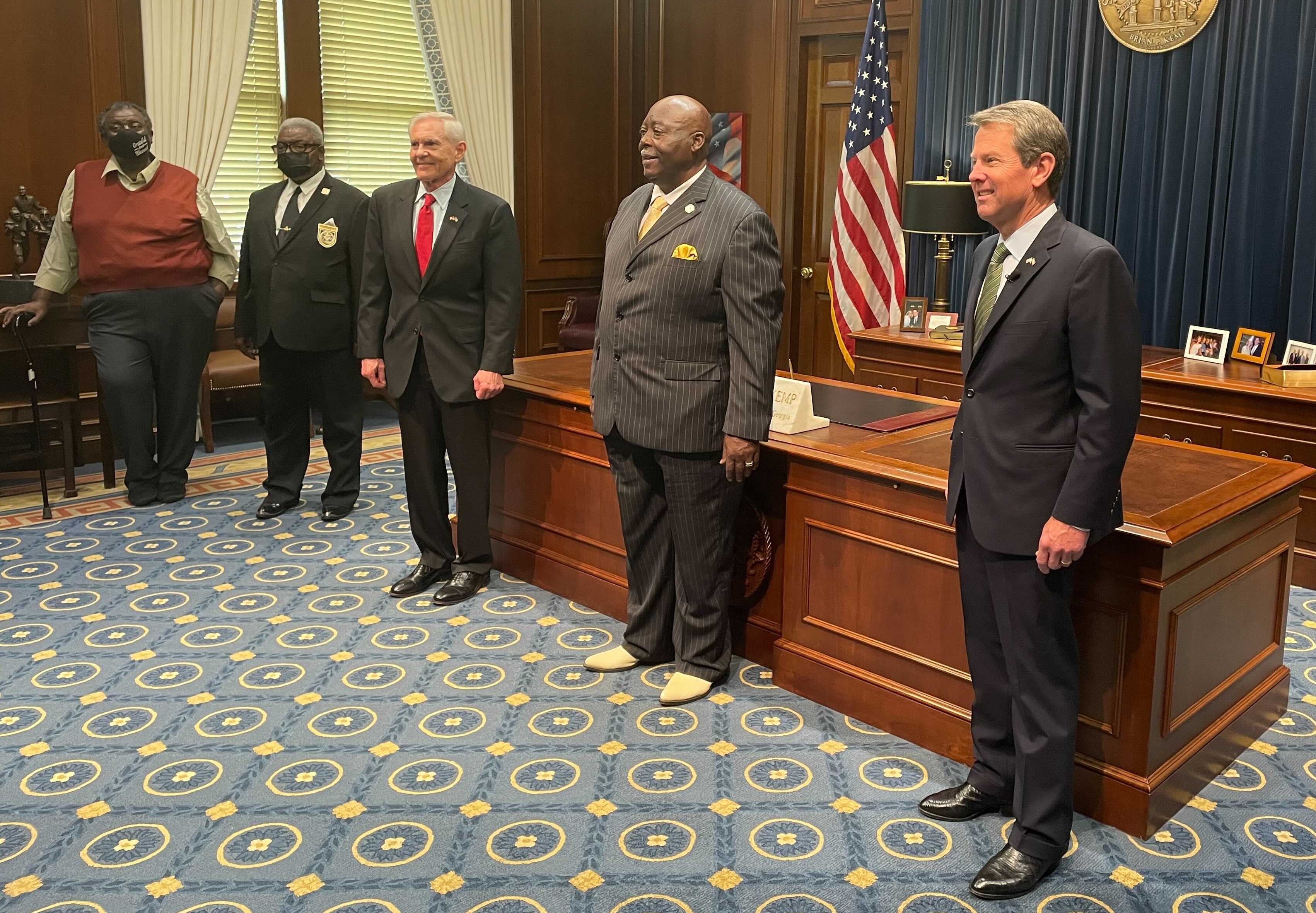

That fact may have fueled some extra agita for potential exhibitors, though the entirety of the memorial association board was appointed by Republican Gov. Brian Kemp and nothing would’ve gotten this far without his approval, tacit or otherwise.

Sims, the Warner executive, said his firm feels “very comfortable about what the SMMA’s intent is for the project, and what the state’s intent is.” Stephens said the exhibit is not about changing the park’s status but “adding to the story.”

“We believe in addition, not subtraction,” Stephens said.

Nevertheless, the exhibit is unlikely to make groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans happy. That organization has previously proposed leaning even more heavily into the Confederacy at the park. And it also remains a mixed bag for advocates who have called for more wide-ranging changes, up to an including removal of the carving itself.

In an emailed statement, the Stone Mountain Action Coalition called the exhibit a “positive and long-overdue step in the right direction.”

But, the grassroots activist group wrote, “there is no ‘celebratory narrative’ or ‘truth-telling’ that Warner Museums can actually do when the exhibit will be in Confederate Memorial Hall, overlooking Confederate flags and the world’s largest Confederate monument, and can only be accessed by streets named after Confederate figures.

“All at a site with no Civil War history or relevancy.”

-

Nov. 2020

Stone Mountain Memorial Association chair Ray Smith says a "21st-century perspective" will come to the park in "months, not years"

-

April 2021

Gov. Kemp appoints Rev. Abraham Mosley at the first Black chair of the memorial association board

-

May 2021

The relocation of Confederate flags on the mountain's walk-up trail and the creation of a 'truth-telling' exhibit are approved

-

Aug. 2021

The memorial association removes the Confederate carving from its logo

-

Sept. 2021

The memorial association contracts with an engineering firm for the Confederate flag relocation; the flags, though, remain in place

-

Oct. 2021

The memorial association issues an RFP for the 'truth-telling' museum exhibit at Memorial Hall

-

May 2022

Thrive Attractions is chosen as the new private management company for the park's revenue-generating attractions

-

Aug. 2022

Thrive formally takes over for longtime management partner Herschend Family Entertainment

-

Nov. 2022

The memorial association selects Warner Museums to create the 'truth-telling' exhibit; the walk-up trail flags remain in place