Atlantic Station reshaped Atlanta 20 years ago. Now, it looks to the future.

Atlantic Station is known today as one of the South’s largest live-work-play districts filled with glassy towers and shops around every corner.

But the project almost never came to be.

Before his partners could put a shovel in the ground, Jim Jacoby, the district’s developer, remembers in the late 1990s when Atlanta’s poor air quality nearly kneecapped his effort to turn a polluted steel mill into a mixed-use icon.

“We were dead in the water,” Jacoby said. Air quality concerns prompted the Environmental Protection Agency to freeze infrastructure funding vital to his project.

Jacoby’s plan managed to persist through that adversity, find unprecedented solutions and open in 2005.

Now 20 years later, Atlantic Station boasts 6,000 residents, 11 million annual visitors, and continues to grow with new office buildings, apartments and hotels. It even has its own ZIP code, and the 17th Street Bridge connecting it to Midtown helped unlock development west of the Downtown Connector.

New development could soon be in the offing, including a hotel set to break ground next year and the potential for millions of square feet of other additions.

The 20th anniversary, Atlanta leaders say, is a testament to the role Atlantic Station played in rewriting the playbook for redeveloping polluted industrial sites known as brownfields.

“(Atlantic Station) became the foundation for subsequent brownfield redevelopments in the state,” said Gerald Pouncey, a longtime environmental and industrial attorney. “It’s opened up opportunities for so many of these properties that otherwise would have stayed abandoned, idle or at least underutilized, and it’s turned them into centers of commerce.”

Atlantic Station also serves as perhaps Atlanta’s most prominent use of a tax allocation district — areas known as TADs where property tax revenue growth is allocated to pay for infrastructure within its boundaries. Mayor Andre Dickens and his allies are on a charm campaign to extend the city’s TADs, potentially a $5 billion effort.

Despite its current influence, Atlantic Station has endured a challenging road and its share of controversy.

Its initial brownfield cleanup was considered the largest in the country at the turn of the 20th century. Its road network, anchored by the 17th Street Bridge, took White House lobbying and an EPA waiver to avoid its “dead in the water” fate, as Jacoby called it. Global events including 9/11, the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic presented their own challenges.

The complex at times has also had to battle a perception of petty crime, something each of its owners have invested considerable resources to address.

But across three generations of ownership, Atlantic Station has managed to remain influential to its peers, relevant among competition and poised for future growth, said Vikram Mehra, senior managing director at Hines, the owner of Atlantic Station since 2015.

“In many respects, it’s synonymous with the city,” Mehra said. “Everybody recognizes the name of Atlantic Station and what it is.”

Many of the district’s largest tenants remain steadfast, such as Dillard’s, Publix, Target and H&M. The project’s Regal Cinemas often serves as the site of star-studded movie premieres, and the theater’s leadership says it ranks among Regal’s busiest locations.

Hines officials added that Atlantic Station has remained flexible to changing mixed-use trends, especially as peer developments in Atlanta and its suburbs gain traction. A Roaring ’20s-themed celebration Saturday is set to highlight that history while indulging in the district’s current cachet.

“We inherited the vision and legacy of some other very enterprising folks,” Mehra said.

Series of hoops

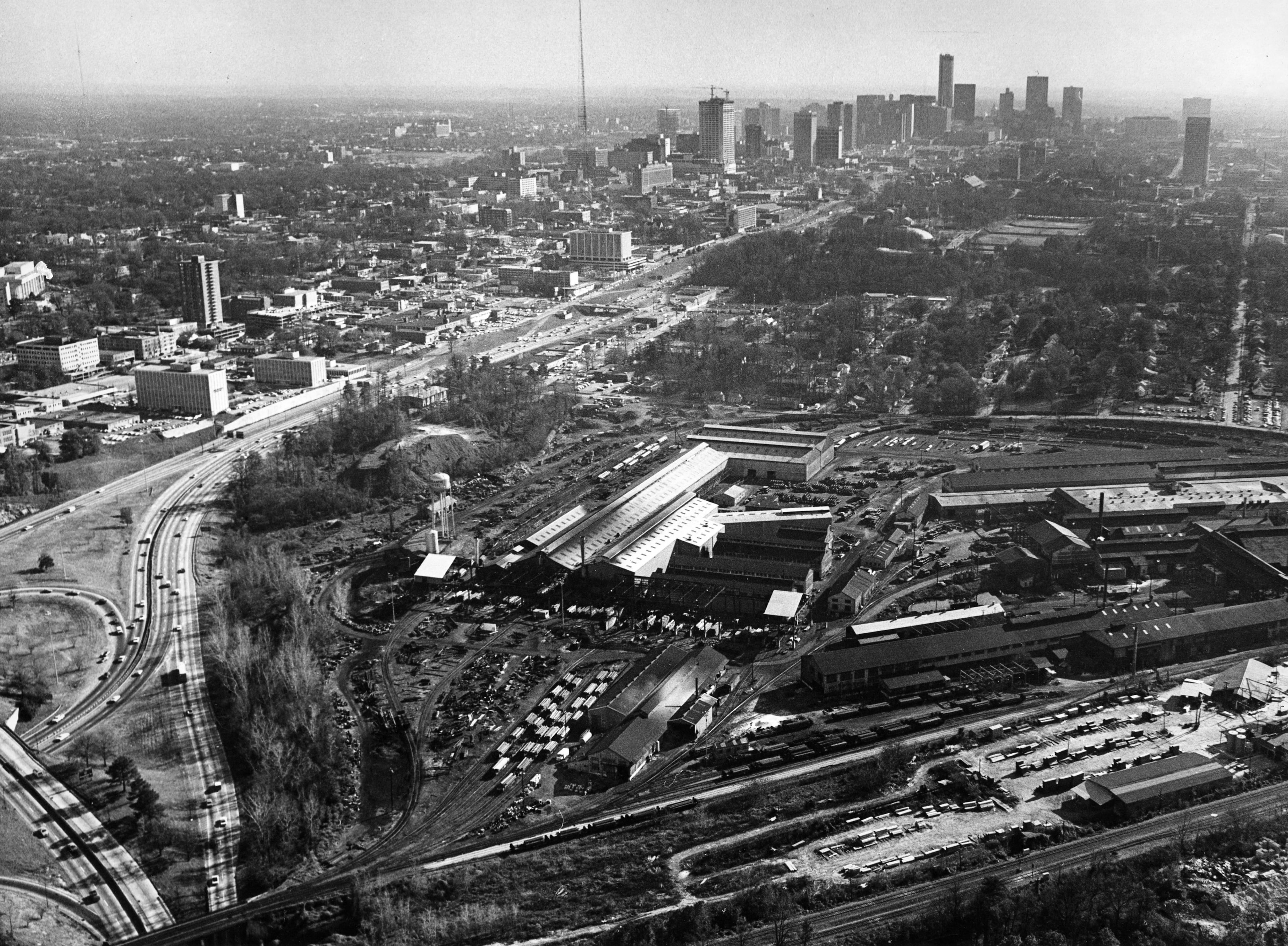

Atlantic Station’s roots date back to 1901 and the Atlanta Steel Hoop Co.

The company smelted steel for niche uses like cotton bale ties and barrel hoops, rebranding as Atlantic Steel Co. in 1915. In the mill’s early years, it smelted enough steel to meet the entire South’s needs, said Eloisa Klementich, president and CEO of Atlanta’s economic development authority Invest Atlanta.

Employment peaked in the 1950s with about 2,300 workers, but the mill’s fortunes would fade. There were fewer than 450 employees by 1997.

The next year, there were none. All that was left was a hulking abandoned mill and all the environmental hazards it presented.

“It needed to be cleaned,” Klementich said. “It required a lot of remediation, so there were developers that looked at it, and several projects that tried to come in. Developers just couldn’t do it because of the cost to remediate the site.”

Discarded earlier ideas for the site included the Olympic Stadium that became Turner Field, the Georgia Aquarium and a skateboard park.

Enter Jacoby, whose namesake development firm was known for building retail projects anchored by Walmarts and Sam’s Clubs. He had a similar vision for the shuttered steel mill.

“It was going to be a Walmart with shops and entertainment,” he said. “It’s (now) a lot of the things we planned on, but it just sort of morphed and got bigger.”

The environmental cleanup also got bigger upon every inspection.

The mitigation involved excavating lead-contaminated soil, demolishing buildings riddled with asbestos, recycling thousands of dump trucks worth of concrete and insulating the site from future pollution. Pouncey, who was tapped by the development team to lead the brownfield mitigation, said the effort was estimated to be an $100 million-plus hoop to jump through.

The cleanup influenced the state Legislature in 2002 to adopt the Georgia Brownfields Act — authored by Pouncey — to make it easier for other polluted industrial sites to undergo redevelopment. Pouncey said more than 1,500 sites across Georgia have either begun or completed brownfield mitigation as a result.

“Without that brownfield precedent, so many other developments could not have taken place,” he said.

Bridging gaps

Despite its intown location, the steel mill site was effectively an island cut off by converging interstates.

Jacoby said Charlie Brown, one of his development partners, often called the Downtown Connector the “downtown disconnector,” dividing Atlanta into eastern and western halves. A bridge envisioned to cross the merging interstates at 17th Street was seen as vital to connect Atlantic Station with the rest of the city.

The EPA blocked federal funding for the project in 1999 over Atlanta’s failing air quality standards. But Jacoby, the city and Gov. Roy Barnes convinced EPA brass the bridge and Atlantic Station would improve air quality in the long-term, receiving the agency’s first waiver to move construction forward.

In addition, the bridge provided a new connection to Atlanta’s Westside, which has undergone a development boom in the decades since.

“We didn’t realize we were opening up all of the westside of Atlanta when we built that bridge there,” Jacoby said.

To support Atlantic Station’s cleanup and infrastructure needs, the city created a TAD for the area. Some $250 million in new property taxes created by the redevelopment helped support the cleanup and infrastructure improvements.

The city sunset the TAD last December because city leaders said it accomplished its revitalization goal.

“It’s a good example of how TADs work and how it really can change the direction for certain parts of the city,” Klementich said. “Could Atlantic Station have happened without the TAD? I would probably say yes, but when would you have gotten there?”

The 138-acre Atlantic Station property was appraised at about $7 million in 1999 before the brownfield mitigation and bridge construction took place. Last year, it was appraised at $843 million — a 12,000% increase.

‘Land to activate’

Two major events in modern American history contributed to Jacoby’s sale of Atlantic Station in 2011: 9/11 and the Great Recession.

His primary investor in Atlantic Station was American International Group, known as AIG, which was among insurers that paid out significant claims in the wake of the 9/11 attacks to victims. The fallout coupled with the 2008 financial crisis thrust AIG to the brink of bankruptcy, prompting an $182 billion federal bailout that required the insurer to sell its holdings — including its stake in Atlantic Station.

North American Properties and CBRE Global Investors took the helm at Atlantic Station until 2015 when they sold it to Hines.

“The first (developer) established a wonderful fabric. The next came in and solidified it and brought in a lot of great elements,” Mehra of Hines said. “And we’ve continued to build on that legacy.”

Since taking over, Hines expanded Atlantic Station’s central green for larger gathering events and built multiple new towers. Those include the Microsoft-anchored Atlantic Yards office complex and the timber-framed T3 West Midtown building, the AMLI apartment tower and the Embassy Suites by Hilton Atlanta Midtown hotel.

Hines declined to provide occupancy figures for Atlantic Station’s various uses.

The district now includes about 8 million square feet of development, and its zoning allows for an additional 4 million square feet.

“The market is tough for development,” Mehra said. “We’ve had a very good run for the last 12-plus years, but despite the strength of the location and being a mixed-use district … while we’ve got a lot more land to activate, we have to be realistic relative to where the marketplace is.”

Next year, Peachtree Group expects to break ground on a dual-branded hotel, and there’s additional property slated for development. No parcels are more prominent than what’s known as the “pinnacle site,” a long asphalt pad home to Cirque du Soleil shows and other special events.

Mehra said the pinnacle site holds lots of potential, adding that the development market needs to be robust in order to avoid underbuilding on the site. Whatever is built, it needs to complement the activity fostered at Atlantic Station.

“All these things have been curated very deliberately by us because we recognize what the project is,” he said. “There’s shopping, entertainment, special events, attractions, festivals, destinations, but it’s also a permanent place for living and working.”

Twenty years later, Jacoby said an Atlanta without Atlantic Station wouldn’t look the same.

“It changed the face of Atlanta,” he said.