How a grand vision and a gift launched 20 years of wonder at Georgia Aquarium

They arrived under the cover of darkness. Two juvenile whale sharks, named Ralph and Norton after characters in “The Honeymooners” sitcom, landed at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport around midnight in June 2005.

Submerged underwater in fiberglass tanks fitted with filtration systems and sensors to monitor oxygen, temperature and salinity, they were bound for their new home at Georgia Aquarium, where they would make history as the first whale sharks ever displayed outside Asia.

Their arrival had been kept secret from all except those who needed to know. Nondisclosure agreements had been signed. The project had been code-named “The Ralph Exhibit” and kept under a “cone of silence,” Georgia Aquarium’s founding executive director Jeff Swanagan told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2005.

The giant teenage fish, collectively weighing about a ton, had been captured off the eastern coast of Taiwan in the Philippine Sea. They had been fated to become food, harvested by Taiwan’s seafood industry.

Instead, they were chosen to become “ambassadors of their species,” said Chris Coco, senior director for aquatic sustainability at Georgia Aquarium, who’s been with the aquarium since 2004.

Coco traveled back and forth to Taiwan multiple times in 2004 and 2005 to facilitate Ralph and Norton’s rescue, using translators to navigate the country’s fishing industry and government regulatory agencies.

After they were captured, Ralph and Norton were housed in a sea pen in Hualien City for several months, where a team of Georgia Aquarium scientists and Taiwanese locals prepared them for their 8,000-mile journey to America.

“The excitement of what we were trying to pull off and bring to Atlanta drove our determination,” he remembered.

From Hualien City, Ralph and Norton flew on a specialized heavy-load, short-runway plane to Taiwan, where they were transferred to a UPS cargo plane.

From there, they flew to Anchorage to clear customs before finally landing in Atlanta. UPS trucks escorted by a police convoy transported the pair downtown, the route carefully timed and mapped to minimize vibration and traffic.

More than 50 professionals — aquarists, divers, engineers, medical staff — waited anxiously at Georgia Aquarium, which had not yet opened.

“When the trucks pulled in, everyone got quiet,” recalled Coco, “We’d spent months preparing, and now it was actually happening.”

Kelly Link, now associate curator for Ocean Voyager, had never seen a whale shark before. She slipped down into the box of murky water with Norton to help him into the stretcher, which would lift him out and into his new home. She couldn’t see much.

“Then, all of a sudden, I just remember his head sort of coming up a little bit so that I could actually see how big he was,” said Link. “It was surreal.”

Early that morning, Ralph and Norton swam their first circles through Ocean Voyager.

Five months later, on Nov. 23, 2005 — 20 years ago this month — Georgia Aquarium opened its doors to the public. Then a 500,000-square-foot facility holding 8 million gallons of water and more than 100,000 animals, it was the largest aquarium in the world, according to Guinness World Records.

Since then, more than 45 million visitors have come to downtown Atlanta to learn and gawk at aquatic wonders. The aquarium is on track to hit 50 million visitors by the end of April 2026, an official said.

An idea takes flight

Georgia Aquarium was conceived by the late Home Depot CEO Bernie Marcus, the founding benefactor who gifted $250 million to build it.

The vision came to him in the air, while aboard a Falcon 900 private jet on a flight back home from Israel in the late 1990s with then-Georgia Gov. Roy Barnes.

On the flight, Marcus and Barnes discussed the entrepreneur’s desire to give something back to the people of Georgia who had welcomed him and his wife, Billi, at a desperate time.

“We came to Atlanta broke, broke, I mean broke,” Marcus told Bridgespan Group, a nonprofit management consulting firm for nonprofits, about his move to Atlanta in the 1970s. “If Home Depot didn’t make it, I was going to go into bankruptcy. (Now) we have all the things in the world that anybody could possibly imagine. It’s a Cinderella story. We remember the people that came and saved our lives.”

The Marcuses had brainstormed other ideas for giving back.

“We had people come to us to build a hospital, build a symphony hall, build a museum. … None of that had real meaning and impact on me,” he told Bridgespan,

Though he “was never a real fish person,” he told Philanthropy Magazine, he asked himself, “What would they enjoy? My employees, my associates — they’re not really symphony people … But an aquarium — everybody loves an aquarium.”

Downtown Atlanta at that time was also suffering from a lack of visitor appeal.

“There were limited activities to bring tourists here and to make them want to stay,” he told Philanthropy. “We do a lot of conventions here, but people never stayed over. They had nowhere to go except maybe a ballgame.”

An aquarium could give them a reason to come and stay.

“I decided that I was going to build it,” Marcus told Bridgespan. “People thought I was nuts.”

Researching the dream

Marcus and Billi set out to travel the globe for inspiration. They visited more than 50 facilities in more than a dozen countries, including Japan, Italy and France.

In Antibes, Billi was captivated by “big white beautiful whales” at Marineland, said Emily Howard, one of the architects who would later help design Georgia Aquarium’s beluga whale exhibit.

In California, Marcus admired the vast shark tanks at Monterey Bay Aquarium, where he witnessed scuba divers descend into the deep to conduct a live feeding.

“I went nuts,” he told AJC in 2001. “I thought it was the greatest thing in the world.”

But it was in Japan where Marcus first encountered whale sharks.

The gentle giants with a wide smile, as big as Greyhound buses, measuring roughly 30 feet long and weighing close to 20,000 pounds, enraptured him.

“When Bernie saw the whale sharks, you knew there was no turning back,” Swanagan told the AJC in 2005.

It was whale sharks that inspired the most ambitious of all the aquarium’s exhibits — Ocean Voyager — a 6.3-million-gallon tank with 2-foot-thick walls and a 60-foot-wide viewing window. The exhibit would become the heart of the aquarium, the cornerstone from which all other exhibits would be designed.

“He wanted people to walk in and just be floored,” said Tom Marschner, a designer for PGAV Destinations who worked on the aquarium’s design. “It was about creating awe — that feeling of being small in the best possible way.”

Developing five distinct worlds

PGAV, a St. Louis-based company specializing in immersive zoo and aquarium environments, including SeaWorld Yas Island, Abu Dhabi and the St. Louis Aquarium, earned the contract to design the aquarium.

Howard, PGAV’s lead designer, still remembers the early planning meetings she had with Marcus’ team.

“Bernie wasn’t just talking about tanks of fish,” she said. “He wanted people to feel something — to be transported somewhere else entirely.”

From their conversations, PGAV began shaping the aquarium’s five connected worlds, each designed around a story, mood and sensory experience.

Georgia Explorer would kick off the journey with the state’s aquatic assets. A coastal-themed play space centered on a boat called Hurricane Hank would encourage children to crawl through crates of shrimp and horseshoe crabs and slide out the mouth of a right whale.

From there, guests would descend into River Scout, walking beneath an overhead river alive with alligators and otters meant to evoke the Chattahoochee and other Southern waterways and freshwater ecosystems.

The temperature would noticeably drop as visitors entered Cold Water Quest, where chilled touch pools and frosty air would lead to encounters with sea otters, penguins and, Billi’s favorite, beluga whales.

Then would come Tropical Diver, a sunlit gallery for one of the largest live-reef exhibits in the country. The exhibit required studies to determine how best to position the skylights and mimic the ocean’s current. A wave machine would generate surf patterns to sustain the fragile coral.

Exceeding all four in scope and grandeur, however, was Ocean Voyager. Guests would begin in a low-lit tunnel before emerging to encounter the massive viewing window, where they would come face-to-face with the largest fish in the world.

The PGAV team helped bring it all to life.

The Coca-Cola Co. gifted the aquarium nine acres next to Centennial Olympic Park on which to build. Originally, the aquarium had been slated for Atlantic Station, but the donation changed its course.

The aquarium opened with 220 full-time and 120 part-time staff. In its first full year, 2006, it attracted 3.7 million visitors, beating both the Empire State Building and the Statue of Liberty for most visitors in the same year (according to The New York Times and U.S. National Park Service, respectively).

The timing of the aquarium’s opening ― just a month after the retail outlets of nearby Atlantic Station opened, on the heels of a major expansion at the High Museum of Art and 18 months before the opening of The World of Coca-Cola museum next door — created what then-Atlanta Mayor Shirley Franklin called “a new energy in the city.”

The aquarium, alongside its neighboring attractions, is largely credited with reviving a dying downtown.

“It’s been one of many driving forces in helping our team attract new and returning events to the city, encouraging people to discover Atlanta,” Charlene Lopez, executive vice president and chief sales officer for the Atlanta Convention and Visitors Bureau, stated in an email.

According to a 2017 impact study (the most recent available), the aquarium increased the Georgia gross domestic product by $4.4 billion and generated an additional $5.2 billion in personal income statewide.

Since inception, it has served more than 1.3 million students through its education programs.

Growth and expansion

Less than a year after opening, the aquarium expanded its Cold Water Quest gallery with the addition of beluga whales.

“Bernie never wanted the facility to stop evolving,” said Marschner. “He wanted it to keep growing and surprising people.”

In 2008, the aquarium made history by adding manta rays, becoming the first aquarium in North America to successfully display the species. The animals were rescued from Durban, South Africa, where they were repeatedly entangled in shark protection nets. They were flown to Atlanta aboard cargo aircraft in a feat of international coordination similar to that of the whale sharks.

The first major facility addition came in 2011, when the aquarium opened its dolphin theater experience, Dolphin Tales (now called Dolphin Coast).

Five years later, the Truist Pier 225 Sea Lion Exhibit opened, replacing Georgia Explorer and adding a 185,000-gallon habitat modeled after California’s rocky coastline. A small stage allows trainers to guide live presentations with sea lions.

And in 2020, Sharks! Predators of the Deep, one of the largest and most immersive shark galleries in the world, was unveiled.

“That one was huge for us,” Marschner said. “It’s less about fear and more about respect — showing people how vital (sharks) are to the ocean.”

Last year, the aquarium opened Explorers Cove, a hands-on gallery dedicated to the dynamic biomes of coastal Georgia, including salt marshes, rivers and the coastal ocean.

With highs come some lows

Not all the aquarium’s milestone moments have been rosy. In 2007, about two years after they arrived in Atlanta, Ralph and Norton died five months apart after their tank was treated with a chemical used to rid fish of parasites, and they stopped eating.

A necropsy conducted on Ralph identified his cause of death as peritonitis, an inflammation of the membrane that lines the abdominal cavity.

Their deaths made national news and sparked debate about the ethics of keeping whale sharks in captivity.

Jason Holmberg, a whale shark researcher for the Earthwatch Institute, told the LA Times in 2007 that the species is known to plunge to depths of more than 3,000 feet and has a migratory pattern that covers thousands of miles.

“All of a sudden,” he said, “they are stuck in a very small tank. It may be the greatest in the world, but it is tiny compared to their natural habitat.”

AJC readers expressed their frustrations online. One reader suggested changing the name of the aquarium to the “Georgia Whale Shark Execution Pool.”

But Mike Boos, chief animal officer for Georgia Aquarium, insisted via a recent email that the aquarium does more good than harm for whale sharks and all its resident aquatic life.

“Unlike our oceans, Georgia Aquarium provides a safe and clean space for marine animals to live, nutritious food and premier veterinary care,” he said. “For many animals, including those who have been stranded, injured or unable to survive on their own, the aquarium is the only place they can thrive.”

Georgia Aquarium also conducts research, he pointed out, that cannot be done in the wild, “research that improves animal health care, impacts conservation and advances our knowledge of the aquatic world.”

The aquarium’s second pair of whale sharks, Trixie and Alice, lived much longer, both at the aquarium for close to 15 years. Whale sharks in the wild generally live to be between 70 to 100 years old, according to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation.

In August, after surviving at the aquarium for more than two decades, Taroko, one of the aquarium’s two remaining whale sharks of six total, had to be euthanized after it failed to respond to treatment for an undetermined health complication.

The aquarium has yet to decide if it will import any more whale sharks.

Right now, the staff is “still in mourning,” said Travis Burke, president and CEO of Georgia Aquarium. “Taroko was someone that was deeply loved, so I think we’re still helping our team get past that. Our focus is on Yushan,” the last remaining whale shark.

Additional setbacks occurred in 2012, when a newborn beluga whale calf died, and another one in 2015. A representative for the aquarium said the cause was never determined, but the deaths prompted animal welfare advocates to question whether beluga whales, or any large mammal, should be in captivity.

And at its 10-year anniversary, the aquarium was denied permission to import 18 wild-caught beluga whales from Russia after it became locked in a legal battle with the federal government and animal welfare advocates.

The future

The next chapter of the aquarium’s story, Burke said, will likely be less about aquatic acquisitions or expansion and more about sustainability and conservation, locally and globally.

“We’re looking at the next 20 years not in terms of how much more we can build,” Burke said, “but how much more we can do — for animals, for ecosystems and for people.”

Much of that work begins in Georgia, he said. In recent years, the aquarium has launched conservation programs along the Flint River, one of the state’s most threatened waterways, including a project that surveys mussels critical to water filtration.

The aquarium is involved in global research projects, too, in the Galápagos, South Africa and St. Helena Island in the UK, studying several subjects including whale shark tagging, manta ray migrations, coral reef restoration and endangered penguins.

Off the coast of Florida, the aquarium is aiding in a study that looks at microplastics in the Tiger Shark food chain.

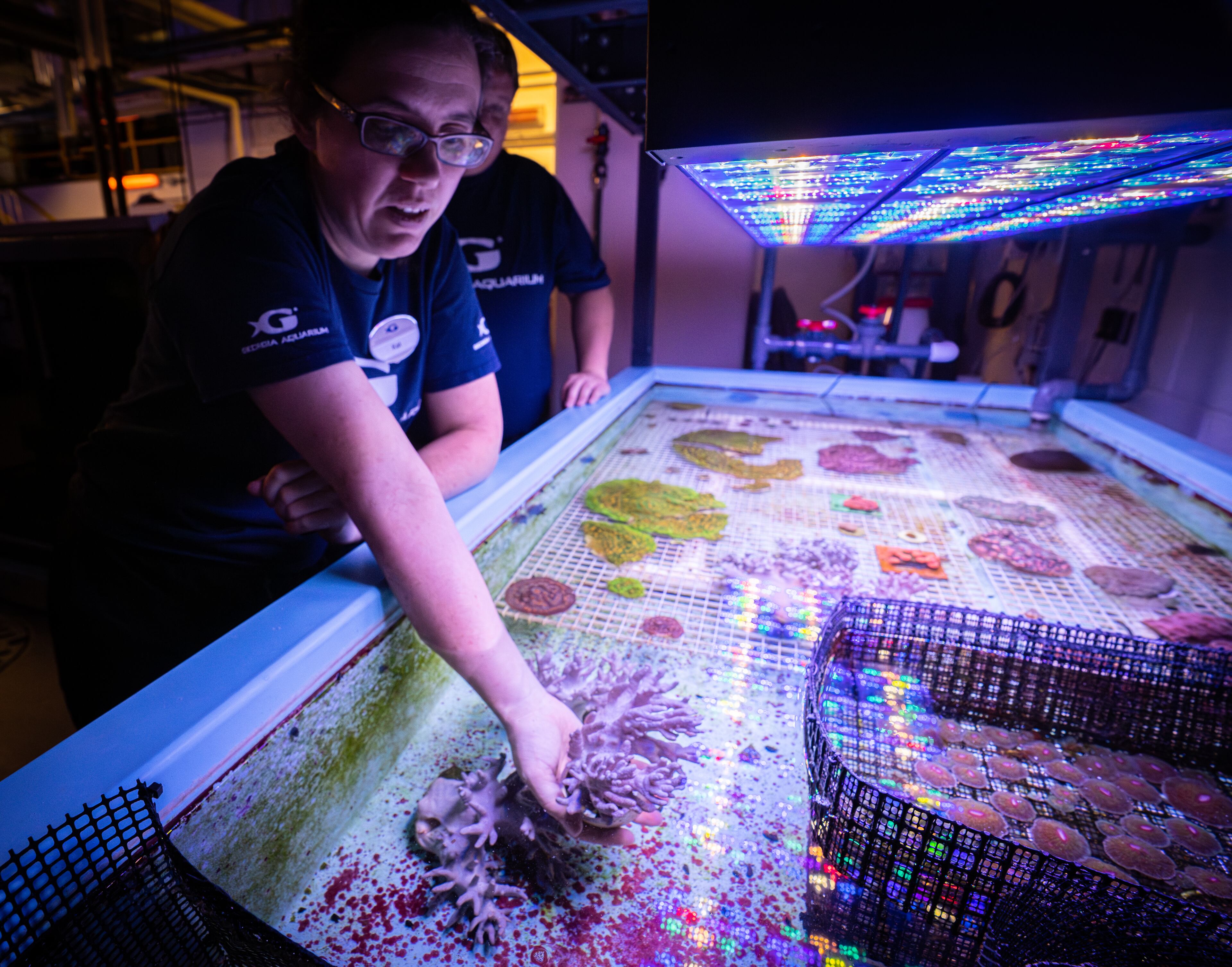

The aquarium is a supporting facility for the Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ Florida Reef Tract Rescue Project. The aquarium cares for more than 100 coral specimens taken from the Florida Keys by the Florida Wildlife Commission and NOAA in the hopes of saving them. The corals are reproduced at the aquarium for genetic diversity; their offspring will be put back into the Florida Keys’ waterways to help bring reef systems back to life after a wave of stony tissue loss disease.

The aquarium’s coral lab also takes in corals confiscated at airports.

A new in-house aquaculture system, Coco said, is being used to raise sustainable fish and crustaceans to feed the aquarium’s inhabitants, reducing dependence on wild-caught seafood.

“We’re trying to close the loop,” he said. “The idea is to have as little reliance as possible on the outside ocean for what we do here.”

Day to day, the overarching goal, Burke said, is the same as it was when Marcus scribbled his big idea on scrap paper on a plane 20 years ago.

“Bernie had a vision to build something that could bring people together and make them feel connected to the ocean and to each other,” Burke said. “Everything we do today — the research, the education, the conservation — it all grows from that. … If (our visitors) fall in love with our animals, if they can see how everything is connected, then we’ve done our job.”

If you go

Georgia Aquarium

9 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday-Friday; 9 a.m.-9 p.m. Saturday; and 9 a.m.-8 p.m. Sunday (hours may vary, check website). $55 and up. 225 Baker St. NW, Atlanta, 404-581-4000. georgiaaquarium.org.

CORRECTION

This article has been updated. A previous version misnamed Tom Marschner and past projects by PGAV.