South African artist protested apartheid with messages still vital today

Visual artists have been fighting the power for centuries, using their artwork to advocate for social change.

Pablo Picasso’s epic 1937 painting “Guernica” was created as a harrowing condemnation of Nazi and Italian fascism during the Spanish Civil War and has stood for decades as a timeless protest against war. Mexican artist Diego Rivera’s murals created from the 1920s through the 1950s, championed working folk and critiqued the oppressive arm of the ruling classes and social inequality. Black artists Faith Ringgold and David Hammons protested the Vietnam War. Contemporary artists, including David Wojnarowicz, the Guerrilla Girls, Barbara Kruger and Nan Goldin have created art that addresses issues from the AIDs crisis and gender discrimination in the art world to censorship and corporate profiteering from the opioid crisis.

African artist Ezrom Legae, a lesser known figure in protest art, addressed the institutionalized racism of the South African system of apartheid that existed from 1948 to 1990 in particular — and authoritarianism in general.

The new High Museum of Art exhibition “Ezrom Legae: Beasts” centers on work the Johannesburg-born artist made between 1967 and 1996. The works selected by the High’s African art curator Lauren Tate Baeza for “Beasts” center on Legae’s use of animals as stand-ins for the winners and losers in South Africa’s brutal police state.

“It was especially important to me that his first U.S. museum exhibition introduce audiences to his range,” Baeza said of her choice to focus on his animal imagery.

Legae cloaked his critique of apartheid in oblique references to flayed birds and mongrel dogs muddied enough to escape notice among South Africa’s ruling class. Under apartheid, every facet of Black South African life, from work to marriage, neighborhood and travel, was controlled by the ruling white minority in a vicious hierarchy that placed Black South Africans at the very bottom.

Under apartheid, Legae was denied the chance to attend university, but pursued art regardless, at public recreation facilities. He studied in the ’60s at the Polly Street Art Centre and the Jubilee Art Centre, later becoming an instructor at Jubilee. As his renown grew, Legae was eventually able to travel to Europe and the United States, where he was moved by both the Black consciousness movement and America’s dark history of persecuting Black and Native Americans.

The illustrator and sculptor was of special interest to Baeza. She calls Legae “an aesthetically remarkable and conceptually important artist whose name we ought to know on this side of the Atlantic.” She compared “Beasts” to her fellow High curator Michael Rooks’ exhibition “Kim Chong Hak, Painter of Seoraksan” (through Nov. 2), the first museum show in the U.S. devoted to another lesser-known artist, South Korean painter Kim Chong Hak. Both exhibitions afford the High an opportunity to champion underrepresented artists with an enormous impact on their national identities.

“Beasts” is also a reflection of Baeza’s mission to expand awareness of 20th century African art, positing it as a geographically complex, important contemporary artistic movement rather than, as it has sometimes been presented, a survey of ancient artifacts. Part of Baeza’s initiative to expand audiences’ understanding of African art’s depth and breadth will involve a reinstallation of the High’s African art galleries.

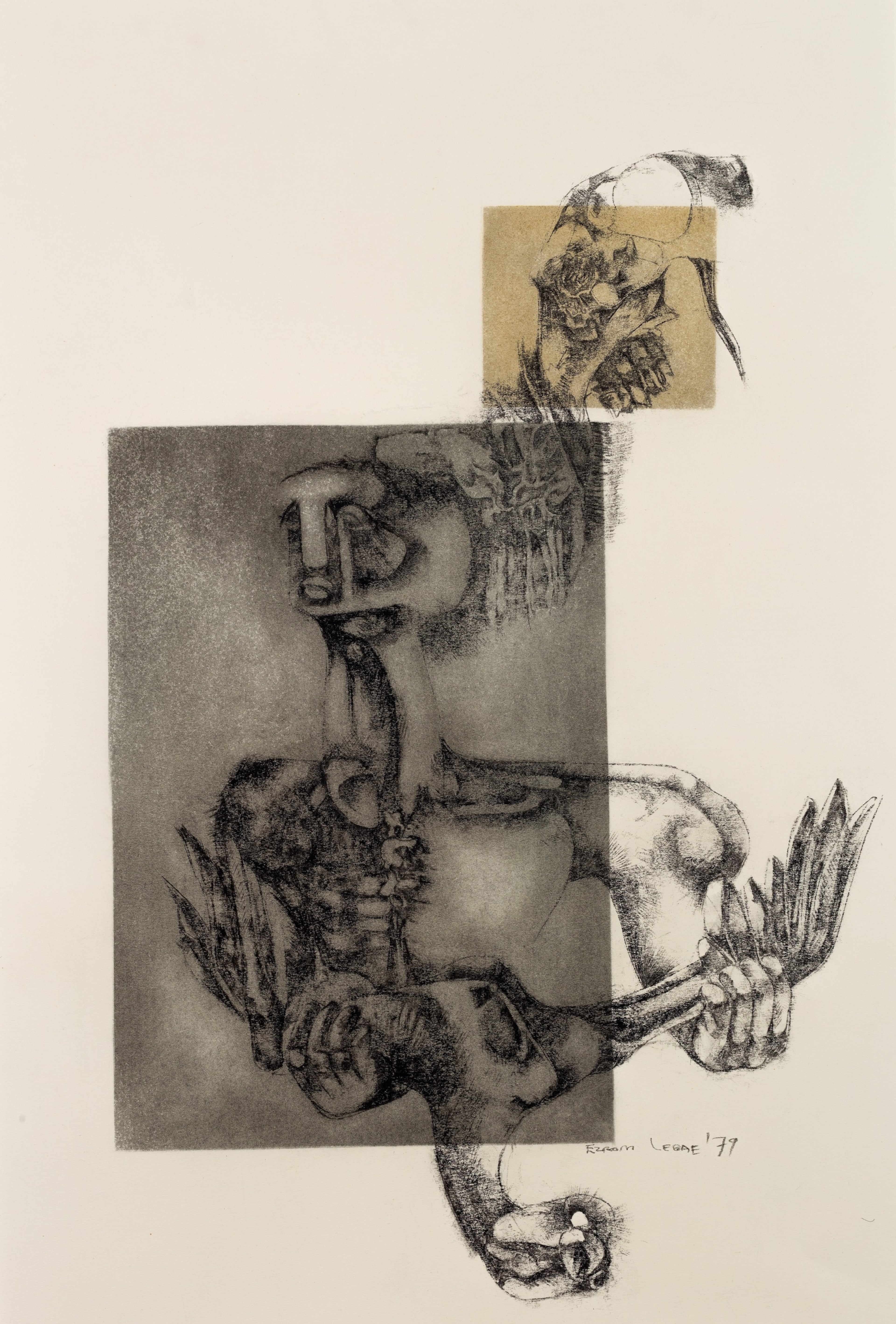

“Beasts” is composed of more than 30 works on paper, in addition to several bronze sculptures. Legae’s illustrations in pencil, ink and charcoal are unsettling whirlwinds of viscera, ribs, beaks, claws, decomposition and disturbing hybrids of the human and the animal. His core players are dogs, chickens, goats, horses and bulls, and his work blends elements of traditional African masks and figurative art and the modernism practiced by artists around the world at the time.

His mark making is frantic, kinetic, with his central animal figures often seeming to move in and out of focus. In these smudged, smoky blurs pulled apart by his use of light and dark, Legae conveys a shape-shifting, nightmarish quality in his drawings of distorted forms attesting to some unseen violence.

“He loved line making,” Baeza said of the skilled draftsman. “He talked about it all the time.”

The works can evoke the quicksilver sketches of Italian Renaissance artists combined with a captivating minimalism, especially when Legae mixes his stark, inky animals with a molten sun blazing above.

The animal proxies for human suffering in Legae’s work were used toward specific political ends, to critique a system without incurring its wrath. But it’s hard not to see these works through a contemporary lens, too, as statements on the inherent miseries inflicted by human beings on animals — from draft horses worked to death to violently eviscerated fowl for the dinner table.

“Horse, four stages of dying,” (1967) in pencil and charcoal on paper is a characteristically disturbing treatment of a wailing, frantic animal suffering a horrific death. The stages are represented in one roundelay, like hell’s merry-go-round. The litany of tragedy continues in the bronze sculptures “Small Mangy Dog Sculpture” (1996) and “Dying Beast” (1993) of a splayed, disemboweled creature strung up by its delicate legs, reminiscent of Alberto Giacometti’s elongated forms.

Legae conveys, in unapologetic terms, the depravity of apartheid with its primal, illogical dog-eat-dog power dynamics that reveal oppression for what it is: a cruel and calculated propaganda steeped in the kind of dehumanization that has fueled genocides from the erasure of Native Americans to the antisemitism of the Nazis to the Rwandan genocide, all of which have excused their cruelty by painting their victims as vermin, insects, animals or pestilence itself.

The artist’s drawings of chickens, as in 1979’s “The Chicken Series” are stand-ins for the South African activist Stephen Biko, who was tortured and killed by South African state police in 1977. For Legae, sacrificial animals such as goats and chickens became metaphors for activists like Biko who fought against their oppressors.

Our present moment feels apt for examinations of the role artists can play in articulating injustice. “I think in daunting and overwhelming times they help us access our interiority,” Baeza said, “and process and articulate the social and political challenges we face.”

VISUAL ARTS PREVIEW

“Ezrom Legae: Beasts”

10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday; noon-5 p.m. Sunday. Through Nov. 16. $23.50. High Museum of Art, 1280 Peachtree St. NE, Atlanta, 404-733-4444, high.org.