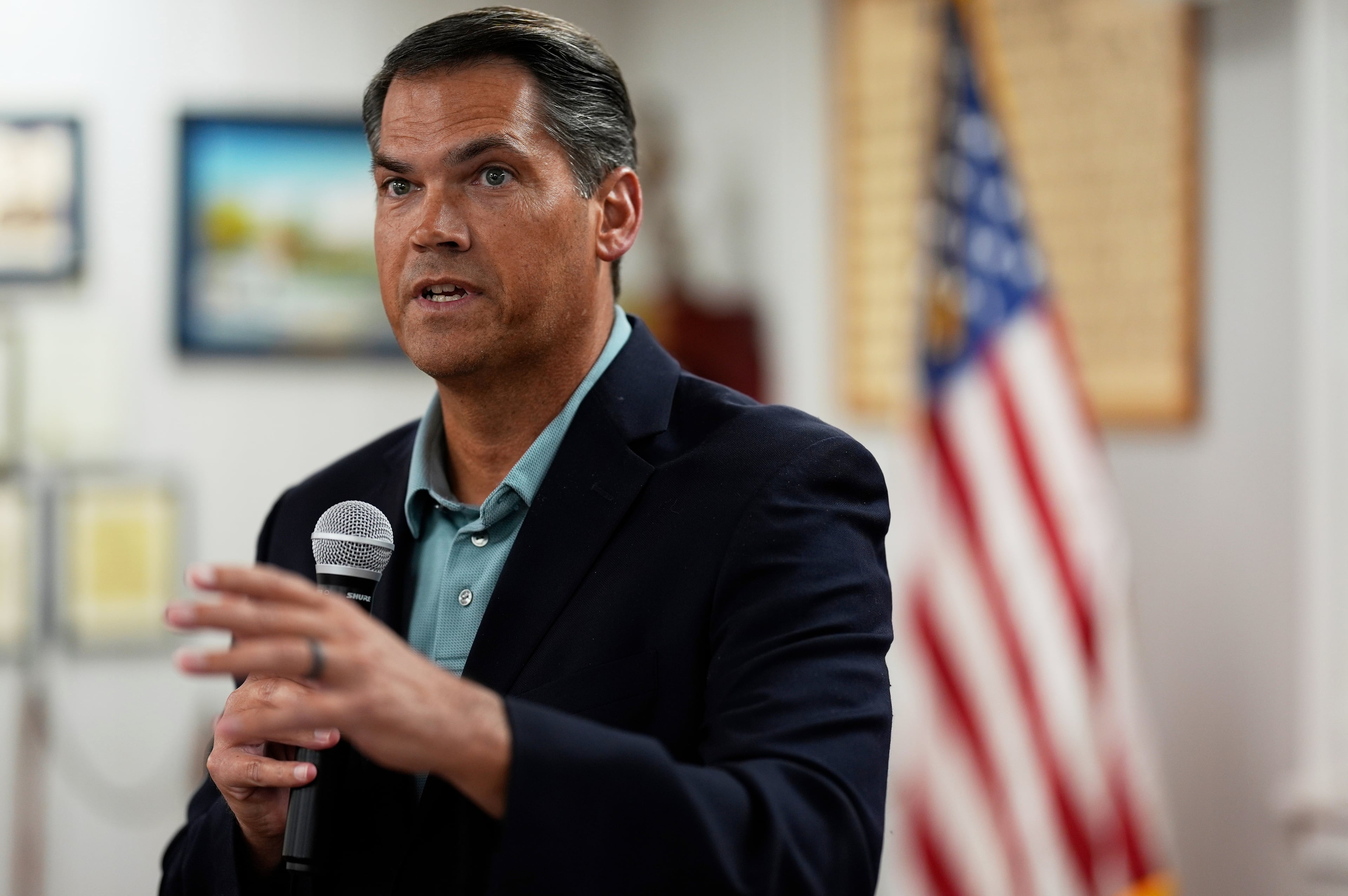

Can Michael Thurmond be Georgia Democrats’ fixer?

COLUMBUS — On more than one occasion, Michael Thurmond has been brought in to fix something that was broken.

In 2013, he was appointed interim superintendent of the DeKalb County School District after it nearly lost its accreditation for mismanagement. He was elected CEO of DeKalb County three years later after the previous CEO was found guilty of attempted extortion and perjury.

Now Thurmond is running for governor of Georgia, hoping his brand of pragmatism and bipartisanship will help Democrats win the governor’s race for the first time in 28 years.

At 72, he wouldn’t be the generational change some Democrats are looking for. But he said he wants this campaign — and possible victory — to be the fix for the state’s increasingly partisan, bitter politics that he thinks is holding Georgia back.

I went to see Thurmond at Holsey Monumental C.M.E. Church last Sunday on a weekend of campaigning that zigzagged him from Atlanta to Columbus, back to Atlanta and Columbus again. It’s a not-unheard-of way to spend a day — or several — as a statewide candidate looking to make inroads with voters wherever you can find them. In the previous week, he’d been to Dawson County, Thomasville, Savannah and Augusta. The week ahead would be more of the same.

“It’s boots on the ground. You have to physically go and be present. You have to do the work,” he said. “It’s physically demanding, but there is no other way.”

In his travels around the state so far, Thurmond said he has heard a common thread from voters no matter where he goes, namely that people feel abandoned by government and by politics.

“Leaders are not speaking to their biggest worries: groceries, car insurance, rent, child care,” he said. “People are not interested in all the partisanship. They want the answer. But first they want to know you care.”

Thurmond knows what it’s like to struggle. He was born a sharecropper’s son in Clarke County, so poor their family could not afford plumbing for an indoor toilet. But they weren’t so destitute that his father didn’t also find a way to purchase what he thought would be Michael’s ticket to prosperity — a set of encyclopedias.

“He couldn’t read and he couldn’t write,” Thurmond remembered of his father. “But he said, ‘Boy, if you memorize everything in these books, you’ll be a genius.’ We didn’t have a bathroom, but we had those encyclopedias.”

With his father sitting by him while he did his homework at night, Thurmond went on to graduate as co-president of his class at Clarke Central High School in Athens. He eventually went to law school and became a lawyer, author and the first Black state representative from Clarke County since Reconstruction.

Eventually, he served three terms as state labor commissioner, too. But GOP strategists around the state say it’s not so much his lengthy resume, but his retail political skills they worry would make him a threat to Republicans in a general election.

It doesn’t get more retail politics than a Sunday sermon at Holsey Monumental, where Thurmond told the parishioners there not to give up their fight in the second term of President Donald Trump.

“Trump may be in the White House, but God is forever on his throne. How can we lose hope or be afraid of tomorrow after all we’ve been through?” he asked the audience.

He said Trump can make his decisions in Washington, but the next governor of Georgia will be the one to decide how the state responds.

“If they cut money from Medicaid in D.C., there’s nothing that stops Georgia from putting it back in Atlanta,” he said. The same holds true for education funds and SNAP food stamp benefits. “But the only way we’re going to do it is put our boots where?” he asked the crowd. “On the ground!” they said.

Thurmond’s second message at church was for the men in the pews, whom he said had been unfairly maligned by the media, and even by Democrats, who blamed Black men for failing to get Vice President Kamala Harris elected in 2024.

“Elon Musk spent $250 million and it’s our fault?!” he asked.

“A whole lot of good Black men on Monday morning get up, get on mass transit, catch a bus, go to work, work hard. Those are good Black men,” he said. “I want to thank you for being the men that you are.”

I sat down with Thurmond for an interview after church to talk about the kind of governor he would want to be. He said he would create more technical programs to make skills-based jobs more available and that Georgia should be the most AI-proficient state in America. He wants to see Medicaid protected and expanded.

But more than any single policy solution, he wants to start to build real consensus in the state around problems and solutions.

“You can’t do it just based on Republican Party ideology, or Democratic ideology for that matter, because you’re leaving half the people behind. And we can’t afford to leave half the people behind,” he said. “I don’t know whether it’s a winning strategy or not. I don’t care. This fight needs to be fought.”

U.S. Rep. Sanford Bishop, D-Albany, has known Thurmond for more than 40 years.

“He’s a good person, and looking at his track record and where he came from, that’s a Horatio Alger story right there,” Bishop said.

Thurmond still has the “G” volume of that set of encyclopedias his father bought him. It’s one of his proudest possessions and displayed on a bookshelf that includes three books he’s written on his own. He said he kept the “G” volume because it includes the entry for the state of Georgia.

It’s hard to imagine his father would not be taken aback by his son’s journey from a Clarke County cotton farm to running to be governor of Georgia. “He’d tell me not to forget where I come from,” Thurmond laughed.

But would his father be proud? Thurmond was silent as his eyes welled up with tears. “Yes.”

As he took out a handkerchief to wipe his eyes, an aide leaned into the pastor’s office to say they’d be late for their next campaign stop in Atlanta if they didn’t leave soon. It was time again to put boots on the ground.