Increasingly diverse, Forsyth County faces racist past

Josh Byrd was raised to be wary of visiting Forsyth County.

His ancestors were among the Black residents violently forced out of Forsyth in September 1912 following the brutal rape and death of an 18-year-old white woman named Mae Crowe, which led to a legacy of wounded race relations that has only recently begun to heal.

Byrd’s family sentiment was always, “Don’t go to Forsyth,” the 38-year-old Roswell native said. “Or if you have to go, ‘leave before sundown.’”

Byrd did the opposite. He moved to Forsyth in 2018.

Forsyth is changing from what it used to be.

In recent years, the county that lies to the north of Fulton and Gwinnett counties has begun to confront its past and today, there are tangible steps taking place.

Byrd, who owns a barbershop in Alpharetta, moved to Forsyth in 2018. He said he became curious when a few clients moved to Forsyth and he started to look for a home with his then-fiancee Breah. Now married, the couple plan to raise their children there, and Byrd said he has enough local business to soon open a location in Cumming, a city in Forsyth.

He is among a group of Black and white men who came together in 2020 to discuss race issues after the death of George Floyd and a Black Lives Matter Protest in Cumming. They named the group, “Better Together.”

“It helped me to understand that as much as things are still the same, things are changing and we have to acknowledge that to encourage people to do more,” Byrd said.

Such talks and soul searching come at a time when the nation is facing deep cultural, political and racial division. The deaths of Black men and women at the hands of police, debate over critical race theory and the banning of books that delve into America’s history of racism fuel the divide.

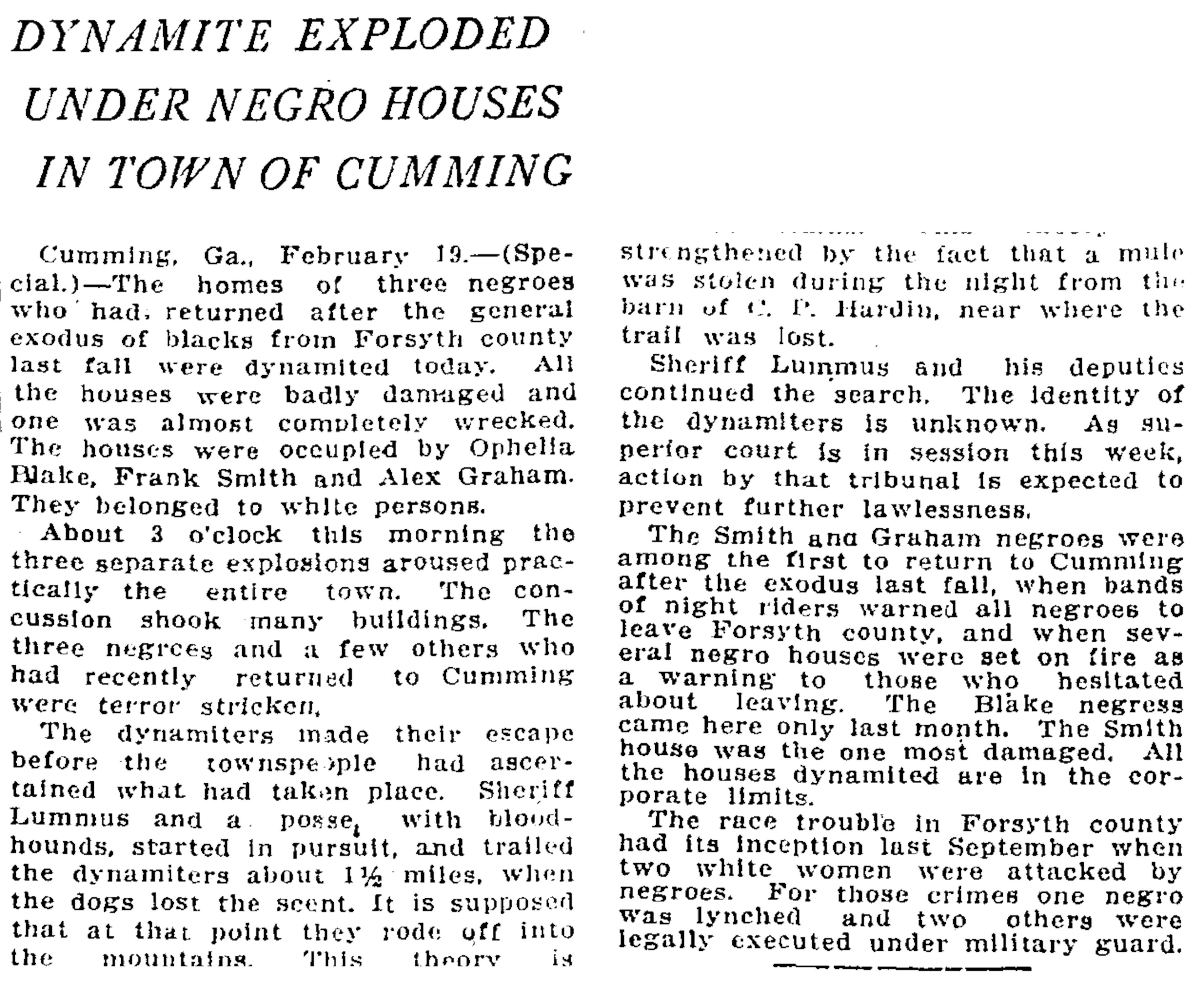

Forsyth’s history of racism is remembered nationally on milestone anniversaries of the racial cleansing and occasions in between. In the decades that followed 1912, a Black person risked being shot or lynched on sight in Forsyth County even if they were with a white person, according to The New Georgia Encyclopedia, a program of Georgia Humanities and the University of Georgia Press.

Over a period of weeks in 1912, night riders drove out more than 1,000 Black residents. By 1920, U.S. Census records show the county was populated with only white residents and remained so for decades. The most recent census count shows Black residents made up 4.4% or 11,000 of 251,283 residents in 2020. Asians represent 15.5% or 40,000 residents and Latinos 9.7% or 24,000 in the county.

Forsyth County population through the years

1912 — Forsyth County was home to 1,098 Black residents in 1912 before the racial cleansing, about 10 percent of the county’s population. More than 1,000 Black people left in the purge.

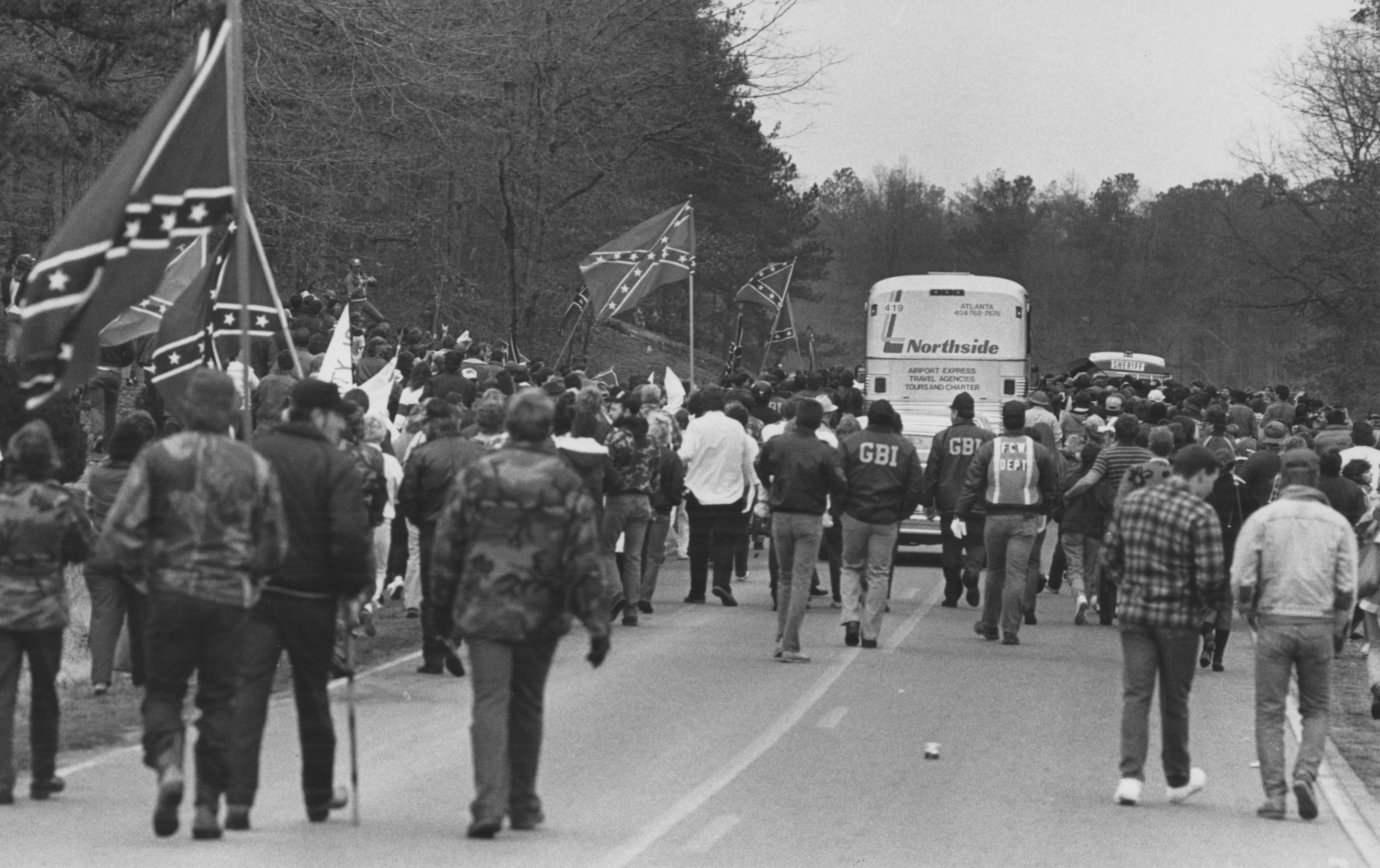

1920-1987 — Forsyth County was 100% white from 1920 through 1940. The 1987 civil rights demonstration led by Hosea Williams was prompted by a white resident, concerned that there were almost no Black people in the county when he moved there five years earlier.

1990 — People of color had started to move back into Forsyth by 1990 when 44,763 people lived in the county: 14 Black, 635 Latinos and 81 Asians.

2010 — There were approximately 7,200 Black residents in Forsyth by 2010, plus 15,000 Latinos, and nearly 9,000 Asians among the population of 175,511.

2020 — Black people made up 4.4% or 11,000 of 251,283 residents. Asians represented 15.5% or 40,000 residents and Latinos 9.7% or 24,000.

SOURCES: US Census, The New Georgia Encyclopedia, History.com, Atlanta Journal-Constitution reports and John Perry.

As part of the renewed effort to address its past, faith leaders have started a scholarship fund for descendants of families of the 1912 racial purge. With the support of the Forsyth County Ministerial Association, they’ve raised more than $100,000 toward their $250,000 goal for The Forsyth Descendants Scholarship. The first scholarships will be awarded in June for the Fall semester.

Durwood Snead, a retired pastor and co-organizer of the scholarship fund said the initiative doesn’t change history but it could eventually lead to healing.

“We know that this doesn’t right a wrong and is not enough but we hope it is a positive step in the right direction,” said Snead, a member of the predominately-white Browns Bridge Church in Cumming.

Forsyth’s history, Snead said, is embarrassing to many longtime white residents. “... But I tell people that the truth will set everybody free,” he said.

Byrd said the Better Together group helped him to cope with the racial divide running through the country in 2020. “I was beginning to get to a place where I was losing some faith in humanity,” he said.

“I tell people that the truth will set everybody free."

Members of the group recently gathered in front of a historical marker near Cumming City Hall marking the beating and lynching of Rob Edwards, 24, one of three Black men who were accused of the 1912 crimes against Mae Crowe. The two others were hanged after a trial.

Byrd’s family cousin Dorothy Pemberton, 95, said she still has vivid memories of her grandmother’s retelling of what happened.

“My grandmother said ... after they [hung Edwards] ... they took the rope and cut it in pieces and made souvenirs for the klansmen and the lawmen ...and people around, and they pinned it to their coats ...,” Pemberton told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

5 historic events of violent racial expulsion

Forsyth County was just one of several places in U.S. history where Black residents experienced lynchings, the burning of their homes and more violent, forced expulsion from their towns. Examples include:

Arkansas 1890s-1920s: This period includes the Elaine Race Massacre in 1919 when hundreds of men, women and children were killed after Black sharecroppers objected to low wages from landowners.

Atlanta Race Riots 1906: Alleged assaults of white women by Black men set off four days of mob violence by white men. At least 25 Black people and two white people were killed in the riot.

Tulsa Race Massacre 1921: The Greenwood district, a thriving community of 10,000 black residents was destroyed in 14 hours, leaving an estimated 300 people dead.

Rosewood Massacre 1923: A mob of more than 1,000 burned Rosewood, an all-black town of about 120 in Florida, leaving several residents dead.

Patrick Phillips, author of “Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America,” moved to the county in 1977 when he was in the second grade. His family lived a few miles from the church grounds where Mae Crowe was buried.

Phillips writes that he spent his boyhood and teen years living in the “bubble” of Forsyth County, where he said he frequently heard white people refer to black people using racial epithets.

“I realized that many people there lived as if the twentieth century had never happened ... Instead, whites in Forsyth carried on as if the racial integration of the South somehow did not apply to them.”

Recently the Historical Society of Cumming/Forsyth County, Leadership Forsyth and others began efforts to restore Tolbert Street Cemetery, a historic cemetery that contains the graves of some early African American Forsyth residents.

Reconciling the Past

Reparations to Black landowners forced to leave their property in 1912 has been discussed over the years including by the 1987 bi-racial committee formed for the county by then-Gov. Joe Frank Harris to address race relations after the civil rights demonstrations. There’s never been agreement.

Dr. Sabin Strickland, pastor of Pleasant Hill Church in Roswell and a consultant to church leaders raising money for the scholarship fund, said the program could turn out to be a model in place of reparations.

“Folks aren’t going to see eye to eye on reparations,” he said.

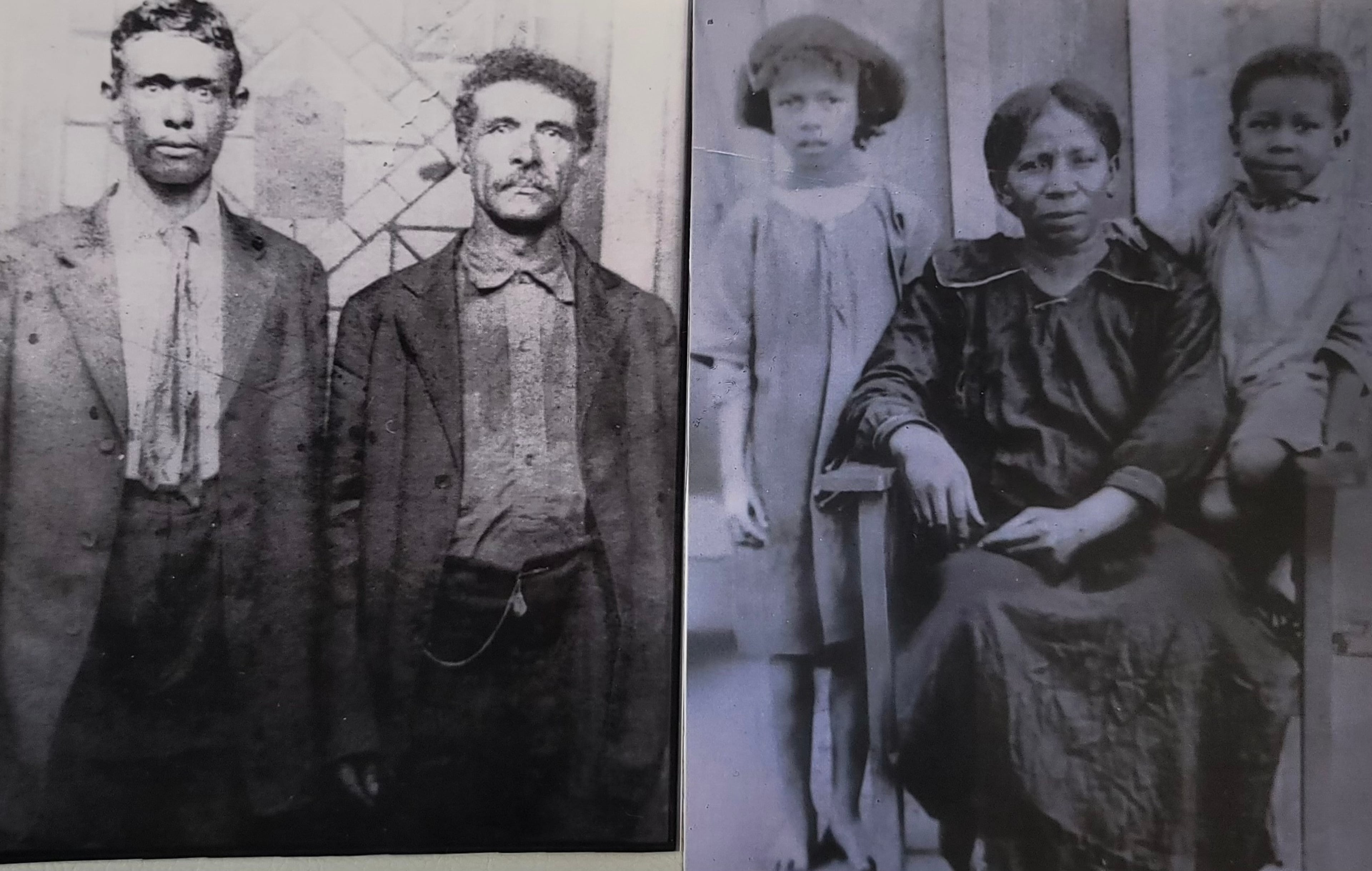

The pastor is Byrd’s uncle. The Strickland family owned a total of 88 acres before the racial cleansing of 1912, family members said.

Today, on a small patch of land in a large wooded backyard near the Forsyth and Gwinnett border, six small white crosses and a sign reading “Strickland Family Cemetery,” mark the resting place of a great uncle Jim Strickland and other family. Their acreage once extended well beyond the little swath.

All of Jim Strickland’s 88 acres were sold to white owners around the late 1930s for $1,100, Sabin said.

Subsequent property owners have respected the family graves.

Gwinnett County Juvenile Court Judge Rodney Harris, who lives in Suwanee, and his cousins go to a cemetery in Forsyth County a couple of times a year to clean off the grave of his relatives. Among them are his great-great-grandfather, Jordan Wells, one of the people he said was forced to flee Forsyth County.

A 1912 story passed down through generations has been of his great-grandfather, Jones (also called Jonah) Parks telling his daughter, Harris’s grandmother, to “get on the wagon, we have to get out of here.”

He said questions about land ownership still linger and he would like to see them addressed. He has not found records of property owned by his relatives but he believes some of those records may be buried or destroyed.

“I don’t think Forsyth is ready for that solution,” he said referring to reparations for land and homes lost in 1912. “I think it’s a tragedy that has never really been addressed. ”