Man locked up for 23 years despite evidence proving his innocence, lawsuit says

A small-town department’s “malicious” police work led to a Georgia man spending more than two decades behind bars despite DNA evidence that should have exonerated him much sooner, according to a new lawsuit.

Witnesses said Sandeep “Sonny” Bharadia was some 250 miles away during the November 2001 home invasion and sexual assault of a young teacher in the town of Thunderbolt, just outside Savannah.

Although investigators had reason to believe Bharadia wasn’t involved in the crime, they pushed forward with a case against him anyway, cutting a deal with the “career criminal” whose DNA would appear on key evidence in later tests, according to the lawsuit. That person’s testimony helped solidify the case against Bharadia, court records show.

Now the man who spent nearly 23 years of his life inside Georgia prisons said he’s struggling to move on.

“The scars of a quarter century of incarceration will plague and haunt him for the rest of his life,” his attorneys said in the suit.

Bharadia, who now lives in Gwinnett County, has always maintained his innocence. Prior to trial, he rejected a deal in which Chatham County prosecutors offered him 10 years in prison in exchange for a guilty plea.

The crime unfolded just months after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City, and Bharadia said discrimination in the wake of 9/11 played a role in his prosecution for the incident.

According to court records, the teacher, who had just returned from a Sunday morning church service, was blindfolded, tied to a chair and held for hours while her apartment was burglarized. The woman was also sexually assaulted.

She was blindfolded for much of the attack, but she testified that she was able, at times, to see under the blindfold and catch glimpses of her attacker.

Emotions were still raw from the 9/11 terrorist attacks that occurred two months earlier. The victim said her attacker spoke with a Middle Eastern accent, told her that al-Qaida had sent him to steal her computer and that he would kill her if she looked at him or did anything stupid. Bharadia is not of Middle Eastern descent.

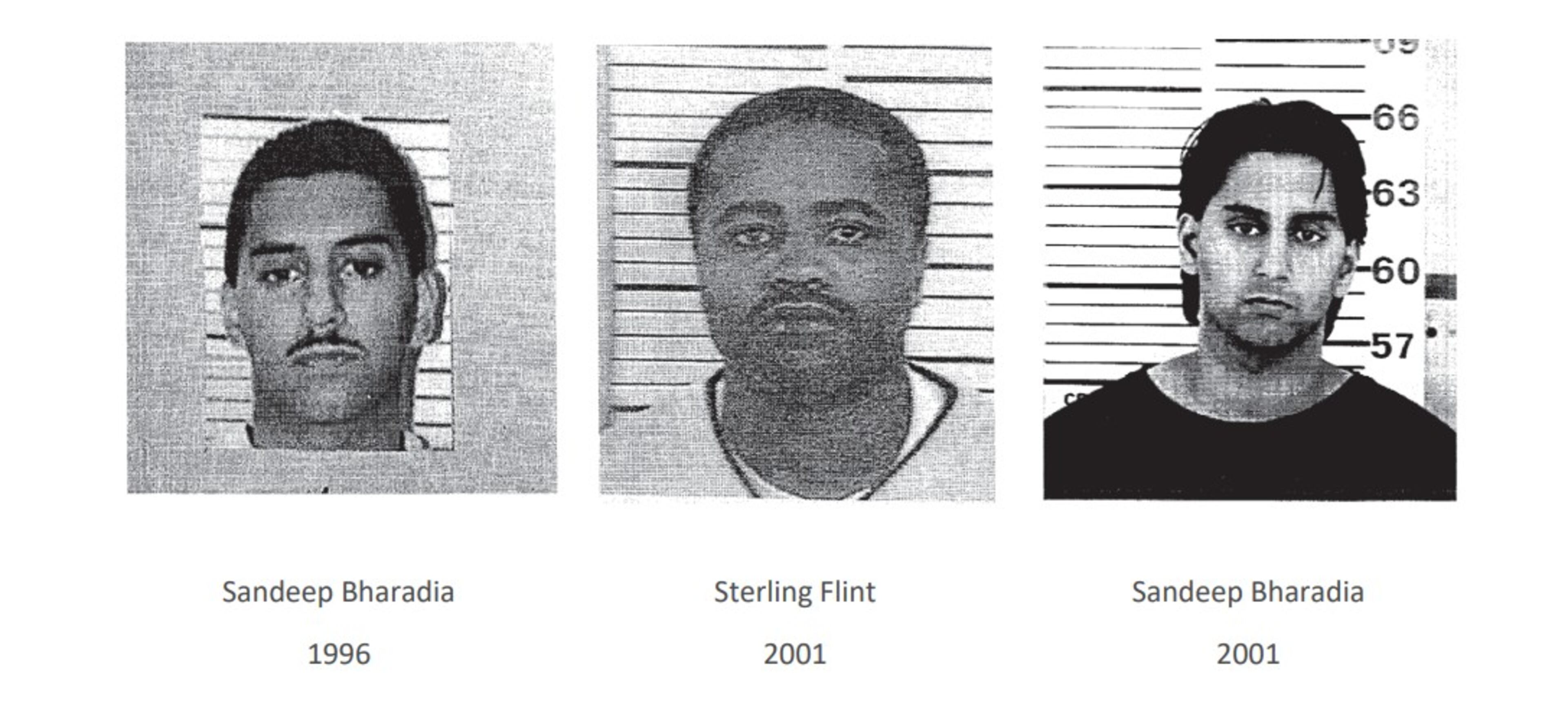

Bharadia was in DeKalb County helping a friend repair a vehicle at the time, and police later found some of the victim’s possessions in the hands of Sterling Flint, according to filings in the case.

Public records show that Flint has done seven stints in Georgia prisons since the 1990s on a variety of charges mostly related to burglary. Flint couldn’t be immediately reached for comment, and he has not been charged as the perpetrator in the case.

However, at the time, he did strike a plea deal on lesser charges related to the case, including receiving stolen property, in exchange for his testimony against Bharadia, records show.

Bharadia says in his suit that, instead of pursuing a case exclusively against Flint, a Thunderbolt police detective with little professional experience instead arranged for Flint to testify against him.

The officer, former Detective Henry “Trey” Conners III, had been in law enforcement for short stints in the mid-1990s before joining the Thunderbolt Police Department in May 2000, according to state police records. He left the department in May 2002 for Savannah’s force, a move that Bharadia alleges played a role in how Conners handled his case.

Bharadia said in his lawsuit that Conners was trying to quickly resolve the case so he could bolster his resume for Savannah. That, combined with what Bharadia says was a “strong personal animus” against him, doomed Bharadia’s defense.

Conners resigned from the Savannah police force in 2003 in lieu of termination after he faced charges in a domestic violence incident, according to state police records.

Conners told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution that he had no recollection of the Bharadia case and declined to comment on the allegations.

The lawsuit also accuses former Police Chief Samuel O’Dwyer of having a role in railroading Bharadia into prison.

State law enforcement records show O’Dwyer had his police certification revoked in 2002, shortly after he resigned as Thunderbolt’s police chief in lieu of termination. It was his last sworn position in Georgia.

His resignation came after a GBI investigation into whether O’Dwyer had instructed a paid informant to lie to a grand jury about the circumstances of undercover drug buys. According to the state law enforcement certification agency, O’Dwyer’s signed resignation stated he was leaving to avoid any potential criminal prosecution.

He did not admit to or deny any wrongdoing as part of the resignation, according to state police records.

O’Dwyer couldn’t be reached for comment, and the police department and city didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“Conners and O’Dwyer knew the sole basis for the criminal action against Sonny was the false and fabricated identification of Sonny that was orchestrated by Conners,” Bharadia alleges in the lawsuit.

After one inconclusive lineup, the lawsuit claims Conners showed the teacher a second photo array “specifically designed” to get her to identify Bharadia as the perpetrator. The picture used in that lineup was five years old and depicted a younger Bharadia with a mustache and shorter hair, according to the filing.

Bharadia’s case was featured in a 2016 AJC investigative series highlighting DNA breakthroughs in Georgia’s criminal cases.

“I feel like there’s a man sitting in prison for a crime he didn’t commit,” Kisha Pitts, a witness in the case, said at the time. “It actually has done something to me because I know he’s innocent and just feel like the justice system failed him.”

Pitts testified as an alibi witness, telling jurors that Bharadia, her husband’s friend from work, spent much of the weekend with their family in DeKalb County. Bharadia was convicted despite her testimony.

A year after his 2003 conviction, DNA testing on a pair of blue and white baseball gloves used in the attack pointed to a separate suspect altogether, although authorities didn’t yet know who, Bharadia’s attorneys said.

Still, he languished in prison another two decades before his conviction was ultimately overturned.

In 2012, the GBI determined the DNA found on those gloves belonged to Flint, the man who testified against Bharadia at trial.

In 2015, the Georgia Supreme Court denied Bharadia’s request for a new trial despite the DNA test results.

A Gwinnett judge overturned Bharadia’s conviction in 2024 after the Georgia Innocence Project and a team of pro-bono attorneys advocated for years on his behalf, case records show.

Bharadia’s federal lawsuit seeks compensatory and punitive damages, as well as legal fees.

Exonerees in Georgia are also eligible for compensation under a law passed earlier this year. The new process is something Bharadia and his legal team say they will also explore as a way to seek some compensation from the state for the time he spent in prison.

Damages for exonerees are capped by the state at $75,000 per year of incarceration, though people who spent time on death row are eligible for more.

Claims can filed for up to three years after their convictions were vacated or three years from the day the law went into effect, which was July 1.

— AJC data specialist Jennifer Peebles contributed to this article.