Some might have forgotten ‘World’s Strongest Man.’ Not in this Georgia town.

TOCCOA — Twenty miles off the interstate between Atlanta and Greenville, an 800-pound bronze figure holds a moment still: a barbell raised high, shoulders flaring, face set.

Outsiders might not know his name. Many Georgians haven’t thought of him in years.

But here, Paul Anderson, once the world’s strongest man, still carries weight.

Before Olympic gold and international headlines, before Cold War exhibitions in the Soviet Union, Anderson scoured the junkyards and farm lots of his youth for scrap heavy enough to redefine the limits of strength.

He built his body from the castoffs of this place. Iron car axles, rusted tractor wheels, even chunks of concrete poured into barrels and old bank safes when every other object proved too light. He dug pits in the dirt to adjust his range of motion, sawed the backs off dining chairs to fashion squat racks, and transformed his family’s basement into a forge of muscle and will.

Word spread about the young man from Toccoa who could lift what no one else could. Reporters came to see for themselves. Magazines printed photos of Anderson training, a barbell across his back, the ends lashed with chains, rocks and iron wheels.

Within a few years, he was a national sensation. He broke records in the 1950s that seemed untouchable, toured the world and appeared on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” The Russians called him chudo prirody, “a wonder of nature.”

Yet around here, back home in the red clay hills of northeast Georgia, he is something simpler, a reminder of what people like to believe about themselves: that with faith, grit, and whatever tools are at hand, you can build something lasting.

The world saw a strongman. Toccoa remembers the man who made himself strong.

“Not many people know about Toccoa, so for somebody from our small town to break world records, it just makes you proud,” said Rebecca Watson, who grew up here and still lives in town.

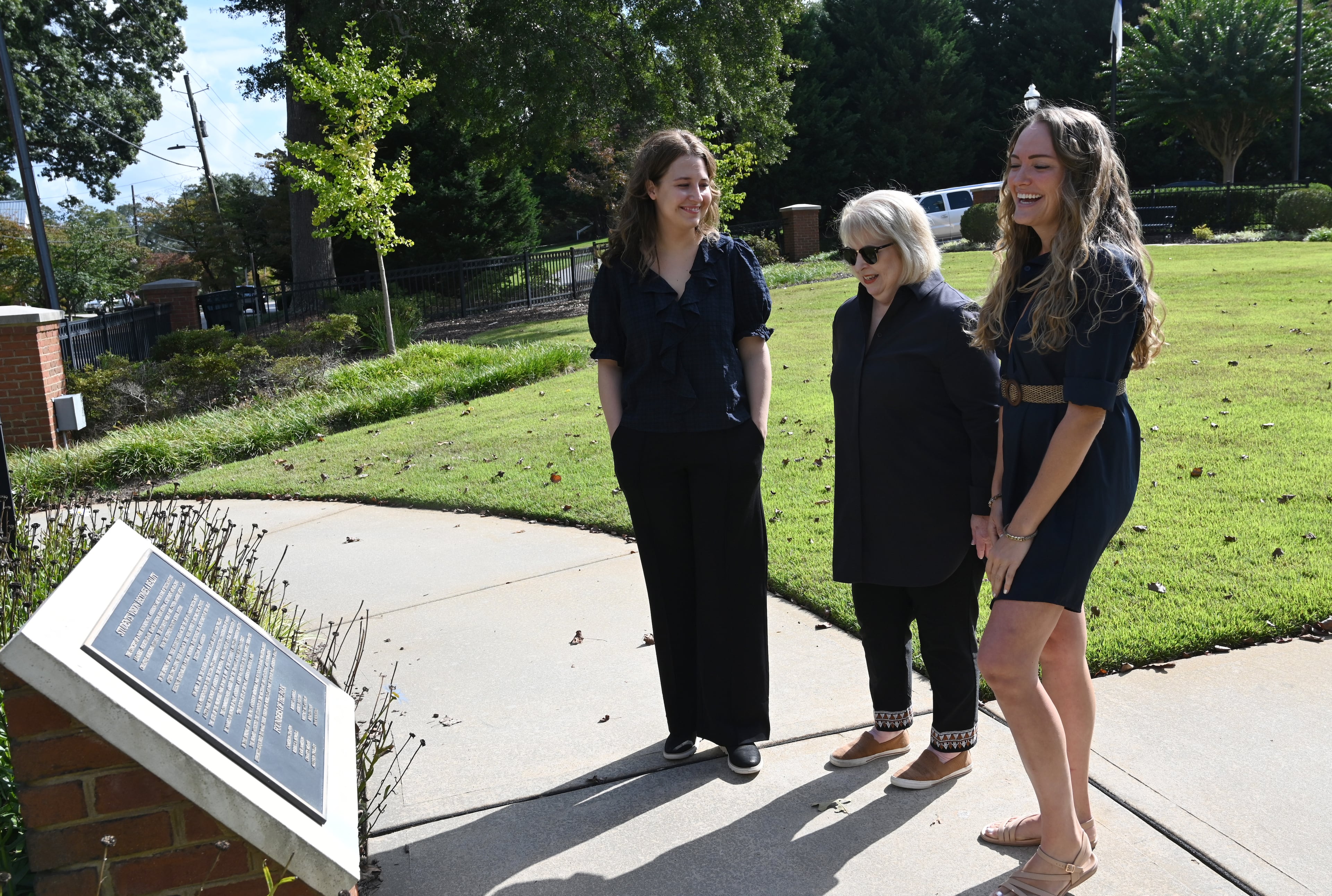

Watson played a role in ensuring Anderson, who died from kidney disease in 1994, remains embedded in this community. She was part of a fourth grade class tasked in 1999 with researching famous Toccoa natives. The more they learned about Anderson, the more they wanted to do.

“The kids wanted to know if there was anything in town about Paul,” Cynthia Sanders, the class teacher, said. “There really wasn’t.”

So the class set out to transform a vacant lot into a park, a short walk from the house where Anderson was born and trained. They sketched designs and presented their pitch to local officials.

“When you grow up in a small town, to know that somebody got out and became famous, it gives you the idea that anybody can do it, no matter where you’re from,” said Allyson Twilley, who delivered a speech before the County Commission.

Anderson’s success story isn’t unique in this state, where tucked-away towns have a way of shaping legends that feel both improbable and inevitable: Jimmy Carter from Plains, baseball great Ty Cobb from Royston, NASCAR champion Bill Elliott from Dawsonville, Gov. Zell Miller from Young Harris.

Anderson’s life-sized statue was erected in the park in Toccoa in 2008 after a local fundraising push. It is surrounded by landscaped gardens, walkways and benches. There’s an annual Christmas tree lighting and a 5K/10K run in November.

As a boy, Anderson battled Bright’s disease, a kidney ailment often fatal in those days, and also scarlet fever. Obsessed with football in his teenage years, his coaches warned him to lay off lifting weights for fear of becoming muscle-bound and too rigid. He played one season at Furman University before leaving school to train full time.

By 1953, Iron Man magazine featured Anderson in his Toccoa basement. Those images and stories of his unconventional methods created national recognition.

Jerry McKenna said he was a teenage football player and “closet weightlifter” when he saw Anderson lift at an auditorium in Cleveland, Ohio, in the spring of 1955.

“I think he clean and jerked 435 pounds, which was a lot,” McKenna said. “I was doing about 200 pounds myself, a kid. So he was doing two-and-a-half times what I was doing.”

Fifty years later, McKenna, 87, drew from that awe when he sculpted the statue now standing in Toccoa.

Later in 1955, Anderson joined a team of Americans traveling to the Soviet Union. In Moscow, Anderson lifted 402.5 pounds over his head, 70 pounds more than the previous Olympic record.

Then-Vice President Richard Nixon told Anderson his performance developed more goodwill between the global adversaries than government officials had in years.

Anderson upped his world records at the 1955 World Championships in Germany. He battled injuries and illness and still won the gold at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, Australia.

Paula Anderson Schaefer said her dad didn’t display his medals or trophies at home.

“He used to say, ‘That and about a nickel will buy you a Coke,’” she said.

After the Olympics, Anderson gave up his amateur status. He was paid for wrestling and boxing matches. He played a role in a Western comedy movie that included one of Mary Tyler Moore’s first big-screen appearances. He performed feats of strength at nightclubs in Reno, Nevada, and appeared on numerous TV shows.

And he made hundreds of visits a year to speak and perform at schools across the country.

Sanders, the teacher who later guided the fourth grade class, remembers Anderson coming to her elementary school in Eastman and returning when she was in high school.

“He had this big square platform, and all kinds of people were put on there, and he lifted it for us,” she said.

Nearly all of Anderson’s earnings were poured into his next pursuit — another legacy that persists decades later in very concrete terms in another corner of the state.

The Paul Anderson Youth Home was established in 1961 in Vidalia. Glenda Anderson Leonard, Paul’s wife until his death, said he developed the idea after meeting teenagers while visiting reform schools and jails.

“He saw young men mixed with older guys and felt they were learning more how to be a criminal there than they were being restored,” she said.

Vidalia, a four-hour drive from Toccoa, was chosen after Anderson performed at the opening of a Piggly Wiggly grocery store and made connections with local officials. Chick-fil-A founder Truett Cathy and G.H. Achenbach, then president of Piggly Wiggly, were among the home’s early donors.

The Christian-based program provides therapeutic counseling, substance-abuse treatment, accredited high school and vocational training and long-term support as graduates transition to adulthood.

Leonard, now 84 and remarried, still lives on the 70-acre grounds and remains hands-on. There are typically 16 boys, between ages 16 and 21, enrolled at a time. She says about 1,400 men have come through the program in its 65 years of operation.

“Paul was a natural leader,” Leonard said. “We just learned by seeing and asking God to make us wise.”

She created a memorabilia room at the youth home with wallpaper made of pictures of Anderson. His medals and other items are on display.

In Toccoa, in addition to the statue and park, there is a granite marker in front of Anderson’s home, where daughter Paula Anderson Schaefer now lives. In the backyard, there’s a safe filled with concrete that would take a crane to move.

Leonard says she knows Anderson’s response if he were alive to see all these markers. He said it all the time.

“How does anybody remember an old weightlifter from 1956?”

Read more AJC ‘Dispatches’ from around Georgia

“Dispatches” are occasional snapshots of people, places, scenes or moments from around Georgia that our reporters come across. They aim to be immersive and aren’t always tied to a news event.

Here are some more dispatches from different corners of the state:

2 hours aboard the slowest ride at the fair for a bird’s-eye view of America

On Jimmy Carter’s 101st birthday, a ‘forever’ stamp and a worm in a jar

America’s ‘smallest church’ is a bit of a big deal on Georgia coast

In melon mecca, watermelon wizards’ ears are sweetly attuned

Green space over greenbacks: Family protects land by selling to Watkinsville

Otis Redding statue, in new spot, conjures up famous tune

Atop Stone Mountain, on the longest day of the year

Georgia’s most blue-collar diner? Psst, it’s near a landfill.

Call to charms? ‘Antiques Roadshow’ attracts treasures for Savannah shoot

Jekyll Island ‘cottage’ on millionaire’s row escapes ruin

A kazoo ensemble tried to set a world record. It was an earful.