Riding the color line: How race built Atlanta’s MARTA system

On weekday mornings in the 1970s, MARTA’s so-called “maid routes” ferried an invisible army of women from Lindbergh Center into Atlanta’s most exclusive neighborhoods.

The buses, numbered in the 700s, ran only twice a day — early enough to deliver Black maids, cooks, and nannies to mansions in Buckhead along Mt. Paran Road and Northside Drive before their employers’ children left for school and late enough to return them home after the dinner dishes were cleaned.

These routes, championed by labor leader Dorothy Bolden, founder of the National Domestic Workers’ Union of America and a disciple of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., were never advertised. They were often scrubbed from MARTA maps and existed only through whispered word-of-mouth or discreet phone calls.

From its birth, MARTA was both indispensable to Black working-class Atlantans and constrained by white fears.

MARTA’s routes, reach and reputation were defined as much by race as by ridership, leaving a legacy of inequity that still shapes how Atlantans move — or don’t move — through their city.

Those tensions only deepened as MARTA tried to grow, sometimes even swallowing Black neighborhoods in the process.

Maynard Jackson knew about the maid routes, recalled playwright Pearl Cleage, who worked on his first mayoral campaign.

“We used to go every morning, very early, when women would be arriving at the station to catch the buses that took them to their jobs in Buckhead,” Cleage said. “We’d hand out campaign literature. I went with Maynard many mornings. He would stick out his hand and say: ‘Good morning! I’m Maynard Jackson, and I’m running for mayor!’ They would laugh and say: ‘We know who you are!’”

For the women who relied on them, the rides were an indispensable lifeline connecting low-wage domestic workers to wealthy white families who depended on their labor.

They were also a microcosm of Atlanta’s racial and economic divides that revealed the contradictions of a system meant to connect a segregated city yet constrained by white suburban fears, business demands and the invisibility of the very workers who needed it most.

Miriam Konrad, a former Georgia State University professor who has written extensively about race, mobility and transportation in Atlanta, said the routes were so covert that there weren’t even designated bus stops.

“There were no signs, because a bus stop was considered an eyesore in those white, wealthy neighborhoods,” Konrad said. “But the maids knew where to wait for the bus.”

In 2001, facing a $12 million annual shortfall, MARTA quietly eliminated the remaining 22 routes.

“So, when you ask what the maid routes represent, it’s racism,” Konrad said. “But more specifically, it’s about who won and who lost. The business elite got what they wanted, while equity goals usually lost out.”

Historian John E. Williams put it more directly: “From the very start, race was completely intertwined in the rapid transit discussion.”

MARTA’s split personality

Even today, as the eighth-largest transit system in the U.S., serving nearly 400,000 passengers a day, MARTA still carries the imprint of those choices.

Critics dismiss it as a service for poor and Black people, while boosters — eager to land Beyoncé concerts, Final Fours, Super Bowls, the FIFA World Cup and tout access to the world’s busiest airport — promote it as essential to Atlanta’s image as a world-class city.

“On one hand, MARTA was about saving a collapsing bus system that domestic workers relied on,” said Jason Henderson, a geography professor at San Francisco State University. “On the other, it was about building a sleek, space-age train for the business elite. Those maid routes captured that contradiction perfectly.”

Atlanta is one of the few major U.S. cities whose transit system never became regional. While major cities like Washington, D.C., and San Francisco tied suburbs to city centers, MARTA serves just Fulton and DeKalb counties and the city of Atlanta.

Suburban counties repeatedly voted it down, often by margins of four to one.

Opponents warned it would import crime, lower property values and speed racial integration. Bumper stickers sneered: “Share Atlanta Crime — Support MARTA.”

Others openly whispered derisively that MARTA stood for “Moving Africans Rapidly Through Atlanta.”

“That phrase captured the way MARTA became racialized — and vilified — by suburban whites,” said Henderson, who wrote his dissertation on Atlanta transportation at the University of Georgia. “The backlash was never just about taxes. It was about race, resentment and fear of integration.

“Public transit was seen as dangerous, wasteful and Black.”

Fears that MARTA would become a pipeline carrying Black Atlantans into white suburbs dogged the system from the start. Cobb, Gwinnett and Clayton voters rejected referendums to join, confining MARTA to Fulton, DeKalb and the city of Atlanta.

MARTA: something bigger?

In 1965, the Georgia General Assembly approved MARTA as a regional transit system meant to serve Atlanta and its five core metro counties — Clayton, Cobb, DeKalb, Fulton and Gwinnett.

Atlanta already had a private bus network, but boosters envisioned something bigger: cheap buses and modern underground trains linking workers and shoppers across a booming metropolis.

The idea looked good on paper, but cracks appeared immediately. While Atlanta and the other four counties approved it, Cobb voters rejected the plan outright.

Even then, the state never put real money behind it.

In 1968, voters in Atlanta and the core counties rejected a property-tax plan to finance operations. The proposal, crafted with little input from Black civic, business and community leaders, ignored the needs of the riders who would become MARTA’s backbone.

Black voters rejected it 2-to-1.

“Of the 36 miles of transit system to be opened by 1975, only 4.3 miles have been earmarked to serve the large Negro west side population,” Jesse Hill, CEO of the Black-owned Atlanta Life Insurance Company and a leading critic of the plan, said in 1968. “This is totally unacceptable, inadequate and unrealistic.”

By 1971, civil rights activists and Black leaders — including Hill — forced their way to the table.

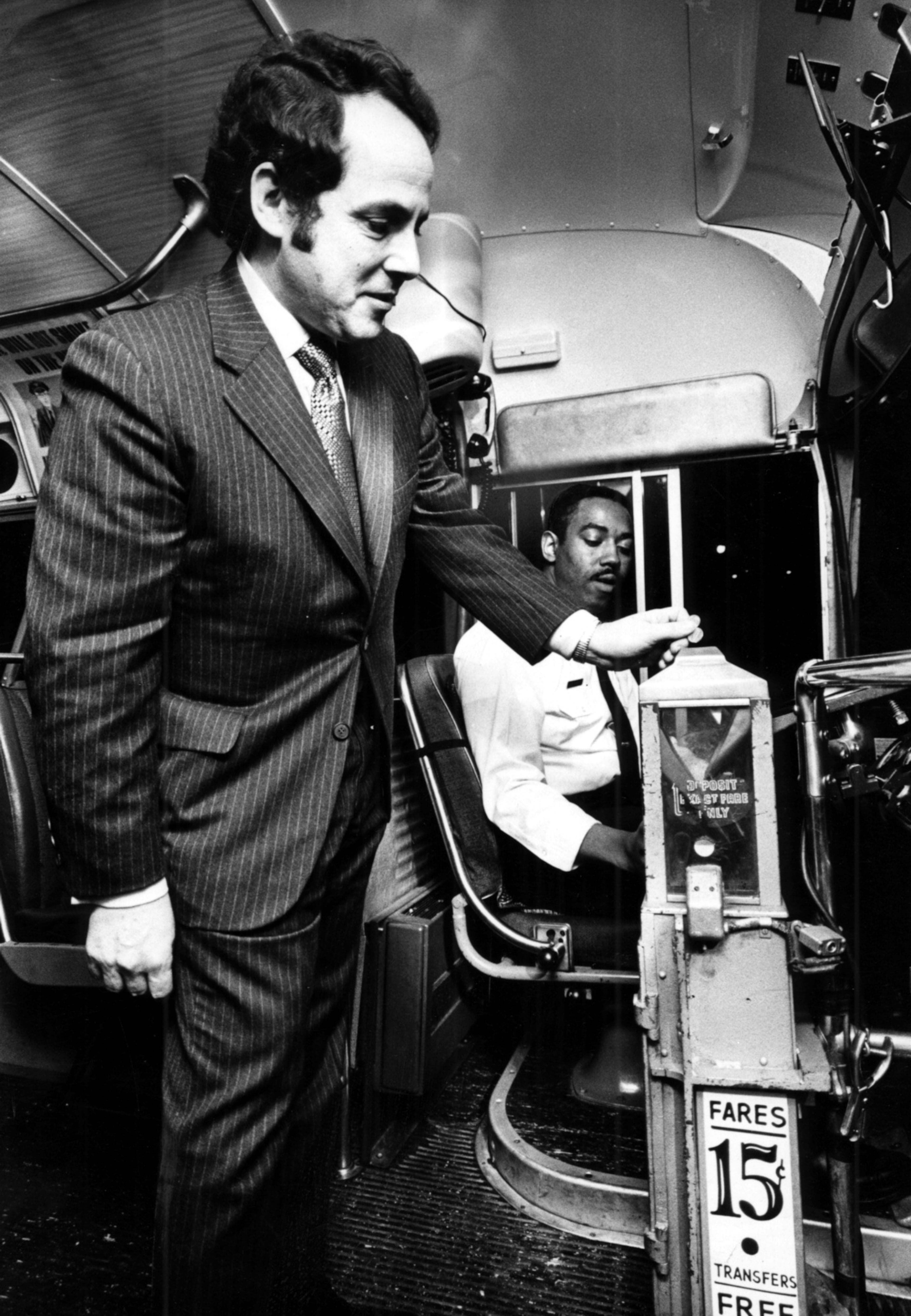

A revised plan, promoted by Atlanta’s last white mayor, Sam Massell, reflected the activist influence and included an expanded bus network, an east-west rail line through Black neighborhoods, a spur to the Perry Homes housing project, minority hiring and contracting guarantees, and a promise to hold fares at 15 cents for seven years.

Black voters in Atlanta supported the plan overwhelmingly.

“Concessions had to be made,” said Williams, the author of the forthcoming “Transcending Barriers: Race, Mobility, and Transportation Planning in Postwar Atlanta, 1944—1975,” which explores transportation planning, segregation and African American civic participation during MARTA’s early era. “MARTA’s creation was in some ways an act of Black civic participation.”

Suburbs pump the brakes

Following Cobb’s early rejection, Clayton and Gwinnett counties, which had swelled with working-class white families fleeing the city during the civil rights era, wanted no part of it.

“Those voters saw MARTA as a threat — inviting the same integration pressures they had fled,” said Williams, who now directs sustainability programs at Columbia University. “The prevailing suburban attitude was: ‘We just escaped Atlanta, why would we invite it back in through transit?’”

In public meetings, opponents warned that trains would bring crime, congestion and — unstated but understood — Black riders into their communities.

During the debates, a Georgia legislator summed up the suburban mindset: “The reason I worked for so many years was to get away from pollution, bad schools, and crime, and I’ll be damned if I’ll see it all follow me.’”

A Cobb County commissioner went further, promising to “stock the Chattahoochee with piranha” to keep MARTA out.

The refusal set the stage for a regional transportation crisis, leaving entire suburbs without mass transit for generations, while highway traffic exploded.

MARTA, cut off from regional support, relied on what critics called the “Atlanta tax.” It was city residents, largely Black, funding a system their white suburban neighbors rejected.

The human cost of progress

MARTA’s inevitable expansion sometimes came at the expense of Black neighborhoods.

La’Neice Littleton of the Atlanta History Center notes that the gleaming Lenox station in Buckhead was only made possible by the destruction of Johnsontown, a historically Black community that was founded in 1913.

“They knew the community would be displaced to make way for the train station,” Littleton said. “There was even a proposal to move the station just 600 feet to preserve Johnsontown, but it didn’t happen. Instead, families who had lived there for decades lost their homes.

“Properties that sold for a few thousand dollars now sit on land worth millions — that’s generational wealth erased.”

The erasure of Johnsontown mirrored the logic of the maid routes, Littleton added.

Like transportation and urban renewal projects across the country, both made Black labor visible only as far as it served white households or white business districts — while Black neighborhoods themselves were deemed expendable.

“History repeats itself. Time changes, but attitudes don’t,” she said. “This isn’t just an Atlanta story. It’s what’s happened in cities across the country.”

The result of it all was transit both ambitious and constrained: sleek rail cars and modern stations inside the perimeter, but no reach into the booming northern suburbs where jobs were moving.

By the 1980s and 1990s, MARTA’s confinement within county lines became a stark symbol of how race shaped transportation politics and the geography of opportunity.

“In the South, public transit is associated with poverty,” Williams said. “Most Atlantans only take MARTA if they don’t own a car — or if they’re going to the airport. Even ridership demographics shift by geography. Below the Arts Center, the train becomes overwhelmingly Black.”

Judah Scott, a 17-year-old senior at Drew Charter School, straddles two Atlantas. He has his own car and freedom, but often leaves it at East Lake Station, a short walk from his home, choosing instead the rumble of MARTA.

Twice a week, he rides downtown to Georgia State University, where he’s enrolled in early college classes. Other times, he hops the train to grab food and hang out with friends.

“I didn’t start riding MARTA by myself until I was 16,” Scott said. “At first, I was nervous. But once I did it the first time, I realized it wasn’t that bad. Ever since then, I’ve been riding constantly.”

Those patterns reflect a broader rhythm: Mornings fill with students of every race, while evenings are dominated by Black Atlantans heading home from work.

“I enjoy the hustle and bustle,” he said. “It feels like I’m part of a city when I take the train into downtown.”

For Scott, MARTA is a choice — a convenience that makes his life easier. For others, riding MARTA is a necessity.

Transit dependency

Several studies have found that 80% of riders were transit-dependent, and a 2000 Brookings Institution report observed that MARTA was “overwhelmingly relied upon by minorities and low-income people who tend to live in the southern parts of the city and the region” while being “underfunded and constrained by suburban resistance.”

That’s the reality for Lurelia Freeman, a teacher at the Museum School in Avondale Estates, who relies on the system the way generations of Black Atlantans have before her.

While not exactly the maid routes of the 1970s, her daily commute is grueling — a daily reminder that what she depends on is also what she despises.

Each weekday, shortly after 5 a.m., Freeman leaves her apartment near Atlantic Station and Northside Drive, one of the city’s old maid routes.

By the time she arrives at her classroom for breakfast duty at 6:30 a.m., she has already endured a 90-minute trek: a walk in the dark to a bus stop, a bus to Arts Center, two trains — first to Five Points, then east to Avondale — and a 25-minute walk through unincorporated DeKalb to her school.

“I do it because I have to,” Freeman said. “I don’t make enough as a teacher to own a car. MARTA is my only option.”

A native Atlantan, she once took pride in the system. She remembers riding the train to Lenox with friends when MARTA was new — clean, safe, dependable.

“Now, I hate it,” she said flatly. “The service has gotten horrendous. Buses are unpredictable, trains are filthy, the app doesn’t work, and I feel unsafe. You never see MARTA police unless there’s a big event happening. Daily riders are invisible.”

Most mornings, about 90% of riders around Freeman are Black working-class men. By evening, students join the mix, including Woodward Academy children escorted by staff — a visual cue of how unsafe their parents believe the system has become.

She said security appears during Falcons games, concerts and parades — but not during her weekday commute. She suspects the sleek new train cars introduced a year and a half ago are being saved for the 2026 World Cup rather than serving daily riders.

“MARTA isn’t serving the people who need it most,” she said. “It’s serving the people it wants to impress.”

Last Monday, on her 90-minute trip home, Freeman’s train stalled at Candler Park, delayed by what she calls “the usual” — technical problems, emergencies or someone on the tracks. She graded papers while waiting, trying to make the most of her time.

Yet, like so many Atlantans before her, she has no choice but to endure.

“I can’t live without it,” Freeman said.

Race, politics and the future

Freeman’s experience underscores a truth that stretches beyond her commute: Even as the area’s demographics shift and the need for a regional transit solution grows more urgent, MARTA is still defined by the riders who depend on it most — Black Atlantans.

Cobb County has repeatedly rejected attempts to join, even as millions travel to Smyrna annually for Atlanta Braves games. Gwinnett said no in 1971, 1990, 2019 and 2020.

But there may be hope.

Cobb and Gwinnett may finally be catching up with Atlanta’s changing demographics, trending Democratic and voting for Stacey Abrams, Joe Biden, Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock.

“MARTA is a most valued asset for Atlanta,” said Williams, the historian. “But it could be so much more if race hadn’t limited it — and continues to limit it. Atlanta cannot grow without MARTA.”

In 1970, when Clayton rejected MARTA, the county was 95% white and just 5% Black. Half a century later, the county has flipped.

The white population has fallen from 82,000 to 25,000, while the Black population has grown from 120,000 to 205,000, according to Census data compiled by the National Historical Geographic Information System at the University of Minnesota.

Today, Clayton is about 70% Black and 10% white.

In 2014, now home to some of the region’s poorest Black neighborhoods, Clayton finally voted to join MARTA.

MARTA is at a crossroads in search of new leadership at a critical time, with huge projects on the horizon. The Future of MARTA is an occasional series looking at the past, current and future of a transit agency that shapes and is shaped by metro Atlanta.