Day in the life of a Georgia shrimper

TOWNSEND — The Sea Fox is easy to recognize by the logo — a caricature of a fox with a shrimp in its mouth — emblazoned on its bow. On this muggy night, it waits in a slip in front of the fish house under the star-speckled heavens. Distant lightning shatters the dark eastern sky, though it threatens no rain. It is eerily quiet, except for the occasional small splashes nearby. The air hangs heavy with the brackish smell of the tidal creek, and all seems normal for 4:30 a.m.

Capt. Eddie Poppell, 61, arrives with his crew, sons Bubba, 40, and Jake, 24, to start outfitting the Sea Fox for a day of shrimping in the shallow coastal waters of Georgia. Ice is shoveled into bins that are dragged from the fish house to the Sea Fox in anticipation of the boat’s refrigerator-sized coolers being filled with shrimp by day’s end. They throw some provisions for the day onto the boat — snacks, water, sodas and cigarettes — and do a routine systems check. The three men go about their tasks quietly, but with the sureness only countless trips can hone.

The Sea Fox ties up at the Valona shrimp dock in McIntosh County, 40 miles south of Savannah and 10 miles from Darien, a sister shrimping community. It is situated near Georgia’s barrier islands, made up of salt marshes, tidal creeks and rivers. Sapelo is its closest neighbor. Beyond the barrier islands, the Atlantic Ocean carries boats that have been roaming the waters searching for shrimp since the early 20th century.

“There is a long history of settlements in the region due to the proximity to productive estuaries and reliance on coastal resources,” says Bryan Fluech, the University of Georgia associate marine extension director. “Technological advances with shrimp nets, motors, ice, etc., in the early 20th century lent itself to more productive shrimping in the region.”

This shrimp dock is home base for weathered faces that seek out the open water for their livelihood. There are challenges, like any profession, and it’s hard work. The conveniences of the 21st century have not changed that fact.

Capt. Eddie checks the navigation electronics and starts the diesel engines with a rumble so loud it seems like it would chase all sea life from the area. The trawler slowly backs out of the slip. He moves the throttle forward and begins to navigate the twists and turns of the meandering creeks and rivers that lead out to the Atlantic. This part of the trip takes two hours. It is a pleasant early morning and the men discuss the weather in anticipation of the catch. The day before had been hot and miserable, and they hope to avoid that predicament this day. Jake lights a cigarette and waits. There isn’t much to do right now, but that will soon change.

The orange glow from the GPS illuminates the dark pilothouse, but Capt. Eddie’s time-honed sense of navigation helps steer the Sea Fox through the dark waters along Blackbeard Creek and through the Creighton Narrows as the sky starts to lighten. Trees on the shore are silhouettes against the dark gray sky, but soon the dawn brings hues of pink, blue and orange in the distance.

Capt. Eddie moved to the McIntosh County area from Waycross with his mother when he was 17 years old. That is when he began shrimping with his stepfather. He started as a deck hand, like his sons, and he’s been fishing ever since.

“I tried other things for a while, but I keep coming back to shrimping,” he says. “I love being out on the water. It’s peaceful and it’s freedom. Nobody is messing with me. I’m my own boss.”

There’s a mischievous glint to Capt. Eddie’s eye, and beneath the stubble his face is lined from living a life in the sun. When he speaks, he doesn’t waste words. Conversation is sparse and unvarnished.

He went in with his brother to buy his first shrimp boat when he was about 20, and he’s been on one boat or another ever since. Shrimping became such a way of life for his family that he built a crib and placed it behind his captain’s chair to carry his infant sons out on the job. Jake and Bubba can truly say they were born into the trade.

“The shrimping life is OK, but it’s a hard way to make a living,” he says. “There is a strong sense of community among shrimpers. They are basically honest folks who you can deal with.”

On the journey out, we only pass one other shrimp boat. Six or seven other trawlers remain at the docks. That has not always been the case.

“About 30 or 40 years ago, you’d have 20 to 30 boats out here at a time,” he says. “You’d have to form a single-file line just to go through the channel. There’s just not as many guys doing this anymore.”

Georgia shrimpers have struggled to survive in an industry now dominated by foreign and domestic shrimp farms. Last year the state had 205 registered trawlers, said Julie Califf, with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources’ coastal resources division. In the late 1970s, close to 1,500 commercial shrimpers held licenses in the state. She attributes the reduction to “a multitude of reasons,” including falling shrimp prices, cost of fuel, cost of maintenance and fewer young people entering the industry.

“It’s a complicated comparison with no direct line between cause and effect,” she says.

Capt. Eddie spends between $300-$600 on fuel every day, depending on how long he stays out. And it’s not only higher prices at the pump but other unforeseen things that affect his bottom line.

“Last year, lumber was astronomical,” he says. “I had to do some repair work on the boat and needed some plywood. I gave my son some money and told him to buy plywood — unless it costs too much. He came back empty-handed.”

Capt. Eddie does all the work on the Sea Fox himself, from engine repairs to carpentry and everything in between. But it isn’t as easy as it was in his youth. Years of hard work and poor lifestyle habits are taking their toll. He admits that his health isn’t as good as it should be; he has a bad heart.

“It’s my own fault — I smoke too much and eat all this fried food.”

As the day gets brighter and the Sea Fox’s diesel engines continue to chug away, Jake and Bubba get busy mending the nets. Using a netting needle, they close up tears and rips for the duration of the ride out.

“One of our problems is with sharks,” Capt Eddie said. “They’re bad. They will rip and tear the nets to get at the fish that are inside. Of course, the nets have to be repaired.”

Dressed in jeans, a plaid shirt and white rubber boots, Capt. Eddie leans back in his chair and uses his feet to operate the wheel as he steers the trawler. The 65-foot, wooden-hull trawler was built in 1979. Behind the captain’s chair on the bridge is a small, sunken bunk that he will use sparingly during the day when one of his sons steers the boat. Beyond his quarters is a mess hall consisting of a sink, oven and a small table. A cramped bathroom and another bunk space complete the small interior. Cruise-ship amenities it does not have, but every inch of the boat is functional.

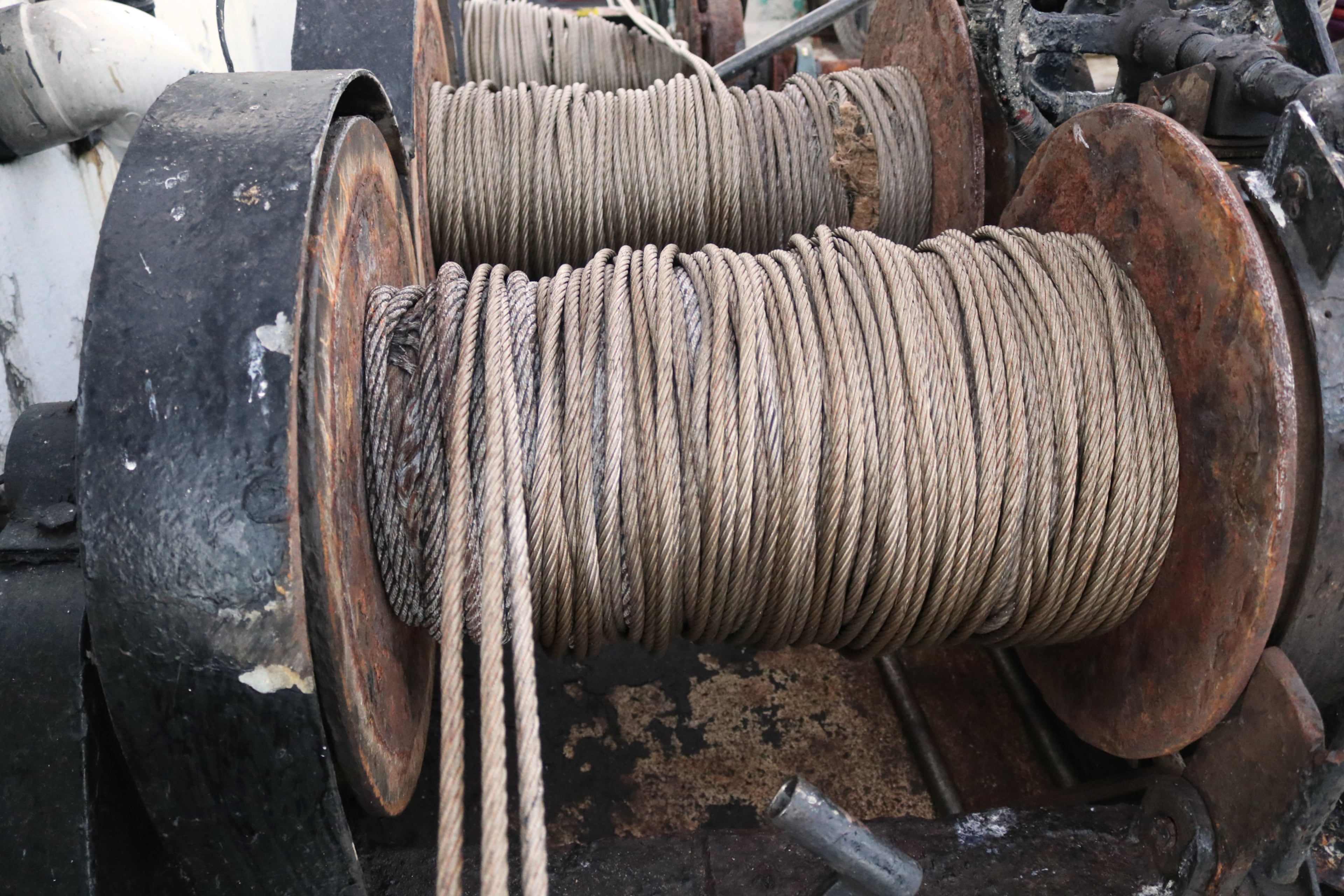

Above deck, the two outriggers — also known as a boom and, to some, the fishing pole — are the heart and soul of the trawler. For traveling this particular morning, they are folded up. When it is time to work, they are lowered and extended out from each side of the boat. Attached to them are sock-shaped nets with wooden doors that are maneuvered by thick steel cables, ropes and winches to catch the shrimp.

The shrimp season in Georgia waters is typically June through December. Three miles from shore are federal waters where shrimp season is open year-round. Capt. Eddie is a full-time shrimper. He tries to get out every day, but it depends on a number of factors, such as weather, tides, prices, presence of shrimp and crew availability.

Around 8 a.m. Capt. Eddie eases up on the throttle off the coast of Saint Catherine’s Island. The area is good for shrimping because of its open, sandy bottom with mixed shell and mud environments. The bottom is not uniformly flat; channels, depressions, slopes and edges provide natural places where shrimp will hang out.

“Shrimpers like Capt. Eddie who have been doing this for a long time are very familiar with these finer differences and know that some areas will hold shrimp better than others, depending on time of year and the tide,” Fluech says. “Captains also often keep logs where they catch shrimp and mark their drags through GPS, which is why they will fish certain areas over others.”

It is time to drop the nets. Jake and Bubba jump into action, working together like fine-tuned instruments. Ropes, cables, chains and pulleys are employed while winches groan to raise the complicated mass of netting into the air, swing it over the side and lower it into the water. With a giant splash, the doors hit the water, followed by the nets, and Capt. Eddie throttles forward to about 2.2 knots.

For two-and-a-half hours, the Sea Fox slowly drags the nets through the water. Time passes at a sea snail’s pace. With land in sight and water flowing past the hull, movement is hard to gauge. Hurricane Larry is far off in the Atlantic but contributes to the swells that rock the Sea Fox back and forth. It is an element that may affect their catch.

“Today’s catch will depend on many factors, like the wind and tides,” says Capt. Eddie. “We’re in about 14 feet of water and we’ll check the try net in a bit.”

The small try net is used to periodically sample the area for concentrations of shrimp. The first check is discouraging.

“Not good,” the captain says. “In 1979, we were getting around $7.50 for a pound of shrimp. Today, we’re only getting around $6.50 per pound, but the prices are coming back up. Fuel prices are higher now, though. I’ve heard that the processor is getting $15 a pound.”

Processors are a kind of middle stop between the shrimp boat and the market. They may de-head the shrimp, as well as sort and grade them if it hasn’t been done on the boat. They also freeze, box and ship the product to buyers.

“Yeah, I think I might be in the wrong part of shrimping,” Capt. Eddie said sardonically. “Plus, I’m getting too old for this. My sons are going to have to take over.”

He’s joking. He has no plans to retire any time soon.

“They’ll find me slumped over the steering wheel before that happens.”

The sons seem ready, though. Jake, a blond-haired, strapping young man who laughs easily, already knows a lot about how to repair, maintain and operate the boat. He also knows these waters and the history.

“You can keep money in your pocket if you do all the repairs yourself,” he says, lighting another cigarette. “And, if you do all the work and upkeep yourself, you know the quality of the work.”

Bubba is more reserved and keeps to himself as he works.

Jake agrees with those who believe wild-caught shrimp is far superior to farmed, especially Georgia’s sweet white crustaceans.

“It has a better flavor and texture,” he says. “But, it’s also the thought of it — the experience. We’re catching shrimp in their natural environment. When people buy wild shrimp, they are sustaining fishermen in small communities. Obviously, I think that’s important.”

Restaurateur Dan Dickerson of the Driftwood Bistro in Jekyll Island wouldn’t use any other kind.

“I’ve been using these locally caught shrimp for a long time,” Dickerson says. “The shrimp are sweeter and more tender than anywhere else in the world. There is just no comparison, and I can’t imagine using anything else.”

Dickerson once did a Lowcountry boil for a customer in Alaska who insisted only Georgia wild shrimp was used.

“I would rather pay a premium price for the highest quality product to keep our customers coming back time and time again,” Dickerson says.

Shortly before noon, Capt. Eddie and sons decide to bring in the catch. Winches hoist the nets into the air and swing them over the deck where Capt. Eddie opens them, dumping the paltry catch on the deck. That is the way shrimping goes. Some days the catch is big — up to 1,000 pounds on a good day — and some days the catch is small.

“It’s just not economically feasible to stay out today,” Jake says. “It’s disappointing. It’s a lot of work for not much shrimp. It’s just one of those days.”

It’s another one of the many tough choices shrimpers in these waters have to make. To stay out longer would cost more in time, fuel and wear, and the day’s haul isn’t going to cover it. Jake takes the wheel and heads back to the docks while Capt. Eddie sprawls out on the bunk.

The refrigerator-sized coolers still hold only ice. The catch is just enough to fill two family-size coolers.

They’ll be at it again, though. Maybe not tomorrow at 4:30 a.m. But it’s their life — they will return.

Read more stories like this by liking Atlanta Restaurant Scene on Facebook, following @ATLDiningNews on Twitter and @ajcdining on Instagram.