A folk art church in Georgia was closed for 25 years. Here’s how it reopened.

Tina Cox had her eyes fixed on one goal when she left her 25-year corporate career at a big-four accounting firm to become executive director of Paradise Garden Foundation in 2018: to reopen Howard Finster’s World’s Folk Art Church.

The church, which in its glory days had been the famous folk artist’s studio, gallery and impromptu pulpit, had been shut down for a quarter century, boarded up and closed off to the public in a dilapidated state unsafe for visitors.

The church had once been “the heart of the garden,” said Beverly Finster, Howard Finster’s daughter. When Cox came on board, the heart was no longer beating.

A “late-bloomer” to Finster fandom, Cox had heard about the folk artist since the ’80s from fellow folk art collectors and art-loving peers, but she did not understand the hype. That is, until she visited Paradise Garden in 1991.

As a regular volunteer for the High Museum, she was tasked one weekend with driving a bus load of patrons two hours northwest from Atlanta to Pennville, the unincorporated area just north of Summerville where Finster had transformed a 4-acre property into a roadside attraction and folk art enclave.

“I walked in the door and there he was, holding court in the front room,” recalled Cox.

He was surrounded by a mesmerized crowd four-rows deep as he spoke in the quick-clipped cadence that recalled his years as a Southern Baptist tent revivalist.

“The room was so packed. I couldn’t even see him hardly,” Cox recalled. “I thought, ‘Why is this guy so popular? I don’t get it.’”

Cox retreated from the crowd to meander the peaceful path that wound through Finster’s garden, weaving around narrow creeks Finster had dug out of the swampland and fashioned like the split river that ran through biblical Eden. Vines and plants thrived.

Cemented into the concrete path were of all kinds of curios and oddities, arranged like mosaics: spare bike parts, a jar containing someone’s tonsils, rusted wrenches, shattered bits of mirror and rims of reading glasses. An old cash register protruded from a dirt mound. Silver hubcaps hung like ornaments on trees. Walls were crafted from recycled bottles and sheds overflowed with broken lawnmowers, farm equipment and cobbler tools.

The more Cox wandered, the more her interest was piqued. She saw at work in the garden the wondrous mind of an inventor, a tinkerer, an artist.

“I think I get it,” she remembered telling herself. “Wow, this is really cool.”

In the following months, Cox spent many Saturday mornings waking up at sunrise to make the drive to Paradise Garden to purchase Finster’s artwork. In that era, he had grown so popular, Cox said, that “if you pulled into the parking lot and there were four cars there already, it was like, ‘Dang.’ You might not be able to get a piece of artwork.”

She was as taken by Finster’s magnetism as she was his creativity.

“He had this really uncanny ability to just center his focus on you,” she said. “The age gap between us disappeared … He was super charismatic. He had a fascinating personality.”

He reminded her of her own father.

“My dad was a Great Depression child also,” she said. “He kept everything and reused everything … when young people visit the garden today, sometimes they don’t make that connection of the time period.”

Artmaking by divine providence

Finster’s popularity and the out-of-towners he attracted to Summerville was surprising to locals who had for years known Finster as a Baptist preacher, bicycle repairman, clock maker and scavenger of discarded objects.

“What happens when your town junk collector becomes a celebrity?” was a question posed by an article on the front page of the Summerville News in September 1987.

Finster credited his fame to divine providence.

Born in 1916 in Valley Head, Alabama, he was 3 years old when he experienced his first vision. According to his origin story, he had been lost in a vine-covered tomato patch when his deceased 14-year-old sister Abbie Rose descended from the sky in a white gown to guide him through the maze and deliver a message: He would be a man of visions.

At 13, he was born-again at a Baptist revival, and by 16 started preaching. He decided to become an artist at the age of 59 when a vision came to him in the shape of a face formed by a paint smudge on his thumb. The face told him to “create sacred art.” He responded that he couldn’t. With no training in art, how could he? But the face insisted.

“It’s like a Bible story,” said Beverly Finster. “God had a bigger plan for him and his work.”

He attempted his first artwork in 1976 by copying the face of George Washington from a dollar bill. He set out to create 5,000 sacred paintings, each inscribed with Bible verses and his mind’s inner monologue. By the time he died in 2001, he had made more than 46,000.

Earthbound logic loosely traces Finster’s first lucky break back to 1975 when a journalist working for Esquire magazine wrote about Finster’s garden. A year later, Finster’s paint-smudged thumb launched his painting career. Then, a series of blessings rocketed his momentum.

In 1983, Athens rock band R.E.M. filmed a music video for its debut single “Radio Free Europe” at Paradise Garden. The band recruited Finster to make their album art for “Reckoning.” The Talking Heads followed suit. Finster’s artwork for their album “Little Creatures” became Rolling Stone magazine’s “Album Cover of the Year” in 1985.

In 1983, Finster’s charm won over national television audiences when he appeared on “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.” The TV host at first seemed to be laughing at Finster, but his fast-talking, Southern charisma and string-picking musicality on the banjo stole the spotlight and dazzled Carson.

In 1984, Finster showed work at the Venice Biennale in Italy. The Wall Street Journal put him on its cover in 1986. People Magazine featured him the following year. By 1989, Coca-Cola sought Finster to create a 13-foot Coke bottle for its centennial celebration. Five years later, the High Museum purchased some of his work for their permanent collection.

Throughout his rise to fame, one project remained central to Finster’s vision: the World’s Folk Art Church.

A church built on faith

When Finster purchased the land for Paradise Garden, it bordered a defunct one-story church with a sagging roof. He dreamed of buying it, but couldn’t afford it.

The pastor who owned it, Billy Wright, held onto the property for him.

“Billy could have sold that church to somebody else,” said Beverly Finster, “but he wanted Daddy to have it. He knew Daddy would make something special out of it.”

Finster envisioned using the old church as the base for a heavenly mansion, multitiered like a wedding cake. He had seen such towering mansions in his dreams and painted them on canvas countless times. He wanted to build one.

When an NEA grant made the purchase of Wright’s defunct church possible in 1982, Finster set out to build what he would call The World’s Folk Art Church.

He built what he saw in his mind’s-eye. He built with faith. He built with conviction and resourcefulness. He did not, however, build with blueprints, construction experience or even a tape measure.

Finster used whatever materials he had on hand: the base of the steeple fashioned from an old dinette table; columns built from circular discs traced with a paint-can lid, then stacked and wrapped in aluminum; windows framed without weatherproofing; walls patched together from salvaged lumber and scrap.

“It was imaginative, but it wasn’t built to last,” said Cox.

For a time, the church thrived and welcomed outsiders. It wasn’t a traditional church that held regular services. There were no pews. Rather it was part art gallery, part art studio, part supply storage and an impromptu pulpit where Finster would deliver off-the-cusp ministry. Many weddings were held at the church, as well as community gatherings.

Nooks and crannies throughout the church displayed quirky bits of art and photographs. Shards of mirror on the outer walls added reflective flashes of light. Visitors could ascend a spiral staircase to the rooftop to take in aerial views of the garden below.

But the flaws were inevitable. Eventually the floors began to sag. Water damage rotted the walls. The base of the steeple disintegrated.

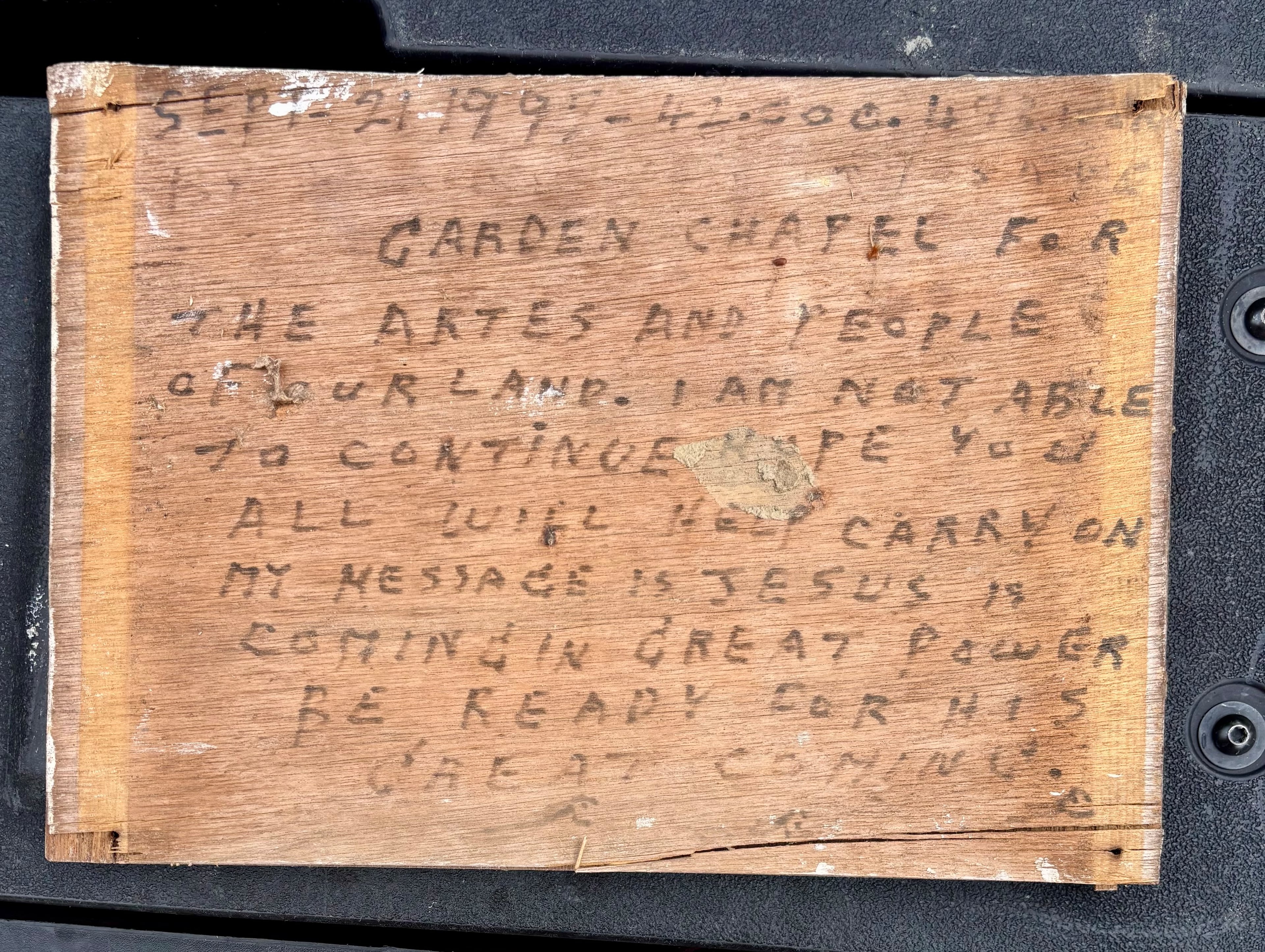

For safety, Finster closed it to the public, nailing a painted sign to the front door. It read: “Sept. 21, 1997. Garden chapel for the artes (sic) and people of our land. I am not able to continue. Hope you all will help carry on my message. Jesus is coming in great power. Be ready for his great coming.”

Resurrected from the swamp

Following Finster’s death, Paradise Garden began to fall into disrepair and was at risk of condemnation. In 2012 the county used an Appalachian Regional Commission grant and donations to buy Paradise Garden for $125,000. The Paradise Garden Foundation was established to manage the property.

Jordan Poole, Cox’s predecessor and the foundation’s first executive director, took the helm and spearheaded a series of restoration projects to rescue the garden from ruin.

“They literally resurrected it from the swamp,” Cox said.

But there were a few projects, including the church, that were in such decay they seemed nearly impossible.

“(The church) was not low-hanging fruit,” Cox said. “It was going to take a number of years to pull together … No one thought we could do it. They all thought the church would just have to be torn down.”

When Cox joined the board in 2016, and two years later became executive director, she was determined to save Finster’s World’s Folk Art Church.

Her first step was to determine what it would take to stabilize the property. Through a $55,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, which was matched with funds from individual donations and the foundation, Cox hired Atlanta-based architectural firm Lord Aeck & Sargent to investigate.

Led by historic preservation specialist Sarah Pitts, the team created a 3D scan, discovered critical structural failures, completed some emergency stabilization measures, oversaw the clean out of archival materials and prepared the structure for future restoration.

Pitts dove into research, studying old photos to uncover exactly what Finster had done to build the church. A feasibility study was ordered to see if funding the restoration project was even plausible. The result was shockingly optimistic.

With the site plan and the feasibility study in hand, Cox and Davia Weatherill, a former board member who became Cox’s successor as the foundation’s new executive director in August, launched a capital campaign in 2024 with a goal of raising $750,000.

Together they smashed their initial capital campaign goals and covered the roughly $600,000 cost of the renovation, plus funded $150,000 to be used toward another building on the garden campus called Pauline‘s House.

In 2024, the final phase of construction began.

Joining Pitts on the restoration was acting project manager Eddy Willingham, a Summerville architect and carpenter. Willingham had known Finster since childhood. The folk artist had repaired Willingham’s bike and been a visiting preacher at vacation Bible School. As an adult, Willingham spent time at Paradise Garden as a contracted carpenter. He helped Finster build the solarium addition on the back of the World’s Folk Art Church.

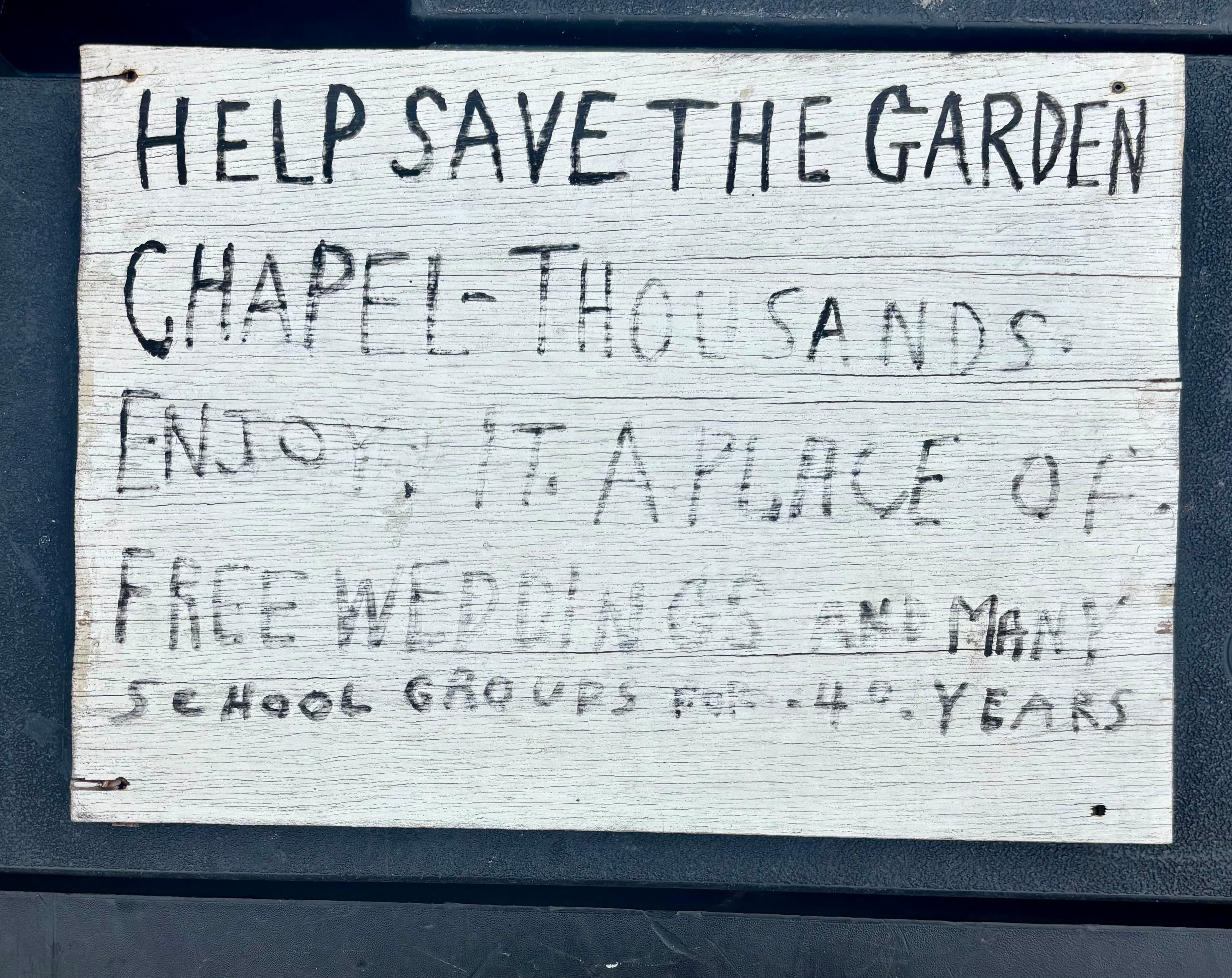

Twenty years later, Willingham was repairing the church’s front door. When he removed the closure sign, he flipped it over to find another painted note from Finster: “Help save the garden chapel. Thousands enjoy it.”

Willingham said yes to Finster’s note.

Pitts and Willingham worked together to bring back every detail of the World’s Folk Art Church, only this time with longevity in mind.

“We agonized about how to retain as much of Finster as possible,” Pitts said.

As they peeled back layers of the structure, they found new surprises in the ways Finster had constructed the church. Their goal was to mimic his methods with more structural integrity, but sourcing material substitutions was a challenge.

“Finding a dinette tabletop as a construction material is not something we learn about in school,” said Pitts.

Willingham’s favorite find: hundreds of bicycle rims stashed underneath the crawl space.

From the time Pitts conducted the first assessment and emergency stabilization phase in 2021 to completion earlier this year, four years had passed.

A long time coming

On June 21, The World’s Folk Art Church officially reopened. At the celebration, Cox took her place at a podium in front of a crowd of roughly 225 VIP guests, including many folk-art collectors who flew in from around the world.

“I might cry,” Cox began.

Visitors listened from long banquet tables decorated with fresh sunflowers where they devoured barbecue brisket sandwiches and cold lemonade.

Cox told stories about Finster. Pitts recounted the arduous process of renovating and preserving the church.

Dignitaries and Finster family members gathered with an oversized pair of scissors for the ceremonial ribbon cutting.

A line formed at the door to the church. Filing up the spiral staircase, hundreds of visitors admired the mirrored walls, photographs and bits of art that encircle the ascension. When they got to the top and exited out onto the open-air porch, they were greeted by a statue of Finster sitting there watching over the garden.

In the midst of the revelry, Beverly Finster sought out Cox in the crowd and wrapped her in an embrace. Daddy would be so pleased, she said.

And so will be the visitors who flock to Finster Fest Sept. 20-21. Typically it’s the 70 folk artists and artisans selling their art and crafts that command center stage at this annual celebration that includes live music and food vendors. But this year, all eyes will most likely be on the newly restored World’s Folk Art Church.

If you go

Finster Fest. 10 a.m.-5 p.m., Sept. 20-21. $10, $5 for Chattooga County residents. Children 12 and under free.

Paradise Garden. 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Sunday. $15, free for Chattooga County residents and children 12 and under. 200 N. Lewis St., Summerville. 706-808-0800. paradisegardenfoundation.org