From 1957-64, Michael Majeeb never missed a Branch Rickey League game. Majeeb was a batboy for the College Park Indians at that time, watching from the dugout as his heroes shined on the field and at the plate. Every game felt like a community event and drew massive crowds.

“Everyone came together - you had people on the side selling barbecue, hamburgers, hot dogs,” Majeeb said. “It was packed. People from everywhere would come to see them play, every Saturday and Sunday.”

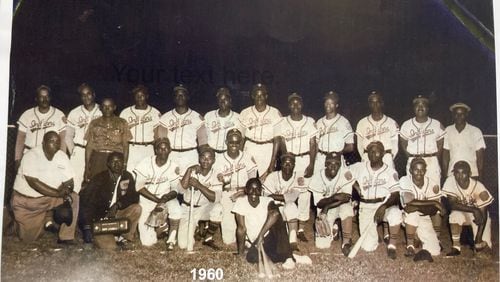

The Branch Rickey League, an organization of around a dozen teams in the Atlanta area, captivated crowds and showcased some of the area’s best Black players in the 1950s and 1960s.

But decades later, the word-of-mouth method that helped the league’s popularity skyrocket had faded, its glory days living on in the memory of its athletes rather than the record of major newspapers. Majeeb is on a mission to change that.

Majeeb started his research seven years ago, inspired by an encounter at his recreation center. One of the boys in the center claimed that his grandfather, Red Wright, played in the Negro Leagues, and Majeeb resolved the conflict by confirming that, in fact, Wright did play Negro Leagues baseball. Since then, Majeeb has traveled to libraries, parsed the archives of the Atlanta Daily World and contacted former players and their families to learn more about the league.

His search connected him with players such as Judge Houston, who played in the Indians’ outfield. Houston could barely wait to join the league as a young baseball player.

“I kept looking at the league that I played in and said, ‘I can do this, I can play here,’” Houston said. “I was very patient. I said, ‘Let me take some batting practice,’ and I worked my way in.”

Houston and Majeeb both attest to the high level of play in the Branch Rickey League. From slick-fielding third baseman Charlie Daniels to powerful slugger Frank McGee – known as “the Black Mickey Mantle” – the Indians had plenty of star power.

Though catching the attention of scouts was a challenge for the Branch Rickey League regulars because of discrimination at the time, several of the league’s players eventually played in the majors. In one memorable exhibition, an All-Star roster of Branch Rickey League players took on the Atlanta Crackers at Ponce de Leon Park, located on the current site of the Ponce City Market, and came out on top.

One of the MLB’s all-time greats even paid the Branch Rickey League a visit and came away impressed.

“Even Hank Aaron, he came and saw the Branch Rickey players play,” Majeeb said. “He tried to encourage the major league, ‘Hey, go down and scout some of those guys in the Branch Rickey League.’”

The Indians’ peak came in 1962, when the club traveled to Wichita, Kansas, and won the Negro Leagues World Series. Majeeb joined the Indians for their cross-country trip and still remembers the thrilling sensation when College Park captured the championship.

Other Branch Rickey teams also had their time in the spotlight. Levi Miller was a rookie third baseman and leadoff hitter for the Rockdale Rawhides when his club brought a no-hitter into the sixth inning.

“In the sixth inning, they hit a line drive toward third,” Miller recalls. “I dove and came down with it and saved the no-hitter. We acted like we just won the World Series.”

While serving as a batboy, Majeeb was an aspiring ballplayer himself and hoped to play in the Branch Rickey League. Instead, the league folded while he was in high school. Majeeb scored a tryout with the Kansas City Royals and played on the Royals’ Single-A and Double-A affiliates before a knee injury ended his playing career.

Majeeb said his goal is to share the stories of the Branch Rickey League players and that giving up has never been an option for him. In past years, he has visited local elementary schools with newspaper clippings to teach the next generation about the players who paved the way.

“I just kept it up because I didn’t want the legacy to die,” Majeeb said. “I knew that maybe one day, these guys could get some recognition.”

Houston compared the legacies of the College Park Indians with Negro Leagues legends such as Cool Papa Bell, Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige, players who also played at a high level but whose performances don’t get the recognition of their MLB peers. That’s what makes Majeeb’s efforts to keep the Branch Rickey League alive so important, Houston says.

“We look back at all of those guys, and we didn’t get a chance to see those guys play - all we can do is hear about them,” Houston said. “That’s what happens with the story that’s told about the College Park Indians.”

“A lot of people didn’t get the chance to see really talented ballplayers, at a real high level, and they played right in your backyard.”

About the Author