Maya Moore, the WNBA star regarded as one of the greats of the sport, will sit out for a second consecutive season and remove herself from contention for the Olympics so she can continue to push for criminal-justice reform and the release of Jonathan Irons, a man she believes is innocent of the crime for which he was sentenced to prison.

“I’m in a really good place right now with my life, and I don’t want to change anything,” Moore, an eight-year Minnesota Lynx forward, told The New York Times in a telephone interview this week from her home in Atlanta. “Basketball has not been foremost in my mind. I’ve been able to rest, and connect with people around me, actually be in their presence after all of these years on the road. And I've been able to be there for Jonathan.”

Irons, now 39, whom she met in 2017 during a visit to the Jefferson City Correctional Center in Missouri, is serving a 50-year sentence after being convicted of burglary and assaulting a homeowner with a gun. Born into severe poverty, Irons was 16 when the incident occurred in a St. Louis suburb. The homeowner testified that Irons was the perpetrator, but there were no corroborating witnesses, fingerprints, footprints, DNA or blood evidence to connect Irons to the crime, his lawyers said.

Irons, who is African American, was tried as an adult and found guilty by an all-white jury.

Moore shocked women's basketball last winter by announcing that she was taking a season off to support Irons as he appealed his conviction. Only 29 years old at the time and still in her prime, she left the door open for a return to the Olympics this summer in Tokyo and the WNBA, where she has led the Lynx to four championships since her rookie season in 2011.

Moore, a 2007 graduate of Collins Hill High School who was the AJC's girls basketball athlete of the year and was chosen Miss Georgia Basketball, said she was fatigued by the grinding year-round schedule that top female basketball players endure to supplement a WNBA salary of roughly $120,000 a season — about one quarter of what LeBron James makes in a single regular-season game. (A new labor pact will boost WNBA salaries and benefits in coming years.) Moore tried to maximize her earnings by playing in leagues around the globe throughout the year with little rest. Including the Olympics, she had rarely had time away from competition since her teens.

Now, her decision to take a second year off is a blow to women's basketball. Moore's haul of Olympic gold medals from the 2012 and 2016 Summer Games, WNBA titles and her leadership of two undefeated championship teams at the University of Connecticut qualify her as one of the greatest winners that basketball has ever known. She also has a charisma that has endeared her to fans and corporate sponsors.

Her absence will affect more than the marketing of the women’s game.

The Lynx, who have lost in the first round of the playoffs the past two years, could use her leadership. So could the Olympic team, which was stunned by the University of Oregon in a November exhibition loss.

“We are going to miss Maya tremendously, but we also respect her decision,” said Carol Callan, director of the U.S. national team. “A player of Maya’s ability does not walk away from the gym lightly. Everyone feels it. The thing that makes her so special is her approach, her dedication, which has always been contagious for our team. We know how devoted she is to what she believes in, and that what she is doing is remarkable.”

Asked during the Times interview this week if she would ever play again, Moore paused to consider her response. “I don’t feel like this is the right time for me to retire,” she said. “Retirement is something that is a big deal, and there is a right way to do it well, and this is not the time for me.”

Nonetheless, she added: “I have had such a unique experience in the game. I got to experience the best of my craft, and I did that multiple times. There is nothing more I wish I could experience.”

Moore’s family had come to know Irons through a prison ministry. He and Moore have become close friends, although she did not speak about their sibling-like bond until after 2016, when she began advocating criminal-justice reform following a series of police shootings of unarmed black men and the killing of five law-enforcement officers by a sniper in Dallas.

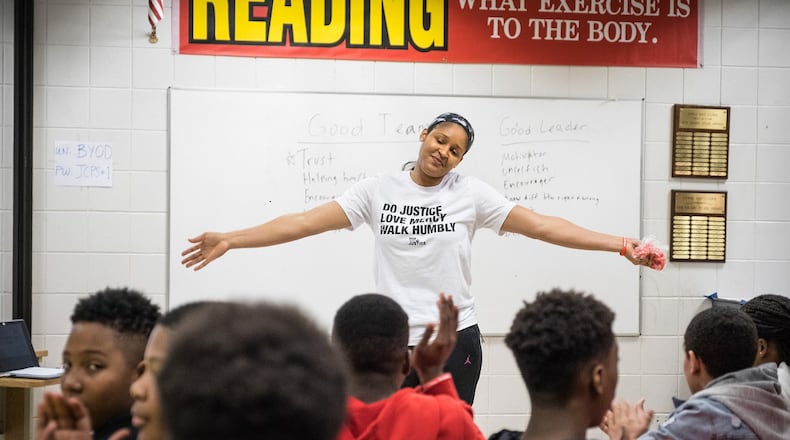

Moore, an evangelical Christian, spent much of her first year away from basketball ministering in Atlanta and spending time with her family. She spoke on panels and was interviewed multiple times on national television about Irons and changes she would like to see in the justice system, particularly in how it treats minorities and the poor.

She traveled often to her hometown Jefferson City, Mo., to confer with Irons and his defense team, which she has helped pay for. Moore and her family also attended a series of courtroom hearings as Judge Daniel Green considered Irons’ appeal.

In October, despite protests from state prosecutors, who argued that Irons’ case should not be reviewed, Green heard nearly six hours of testimony. Moore watched as Irons took the witness stand in shackles to state his innocence and face cross-examination — something a public defender had kept him from doing at his original trial, citing his youth and lack of education.

Asked about the case this week, a spokesman for the Missouri Attorney General’s Office declined to comment.

Additional court appearances are likely in the coming months, including a hearing next week, as Green considers new expert testimony and reviews the results of a test he ordered of fingerprints discovered at the crime scene that match neither Irons nor the homeowner.

In a profile published by The Times in June, Moore expressed optimism that Irons’ conviction could be overturned. Now, Moore believes passionately that Irons will be freed.

“We just have to keep being patient,” she said. “And keep having faith.”

About the Author