Georgia counties are dying: Data shows ‘God’s Country’ is hollowing out

Every now and then, you see something that’s a holy (smokes!) moment. And an old number-crunching author/researcher named Charles Hayslett provided one this time.

Hayslett has researched Georgia for decades and writes a blog called Trouble in God’s Country, which documents rural counties dying on the vine.

His work has been so influential that the state House created a legislative committee to try and address the long-term deterioration.

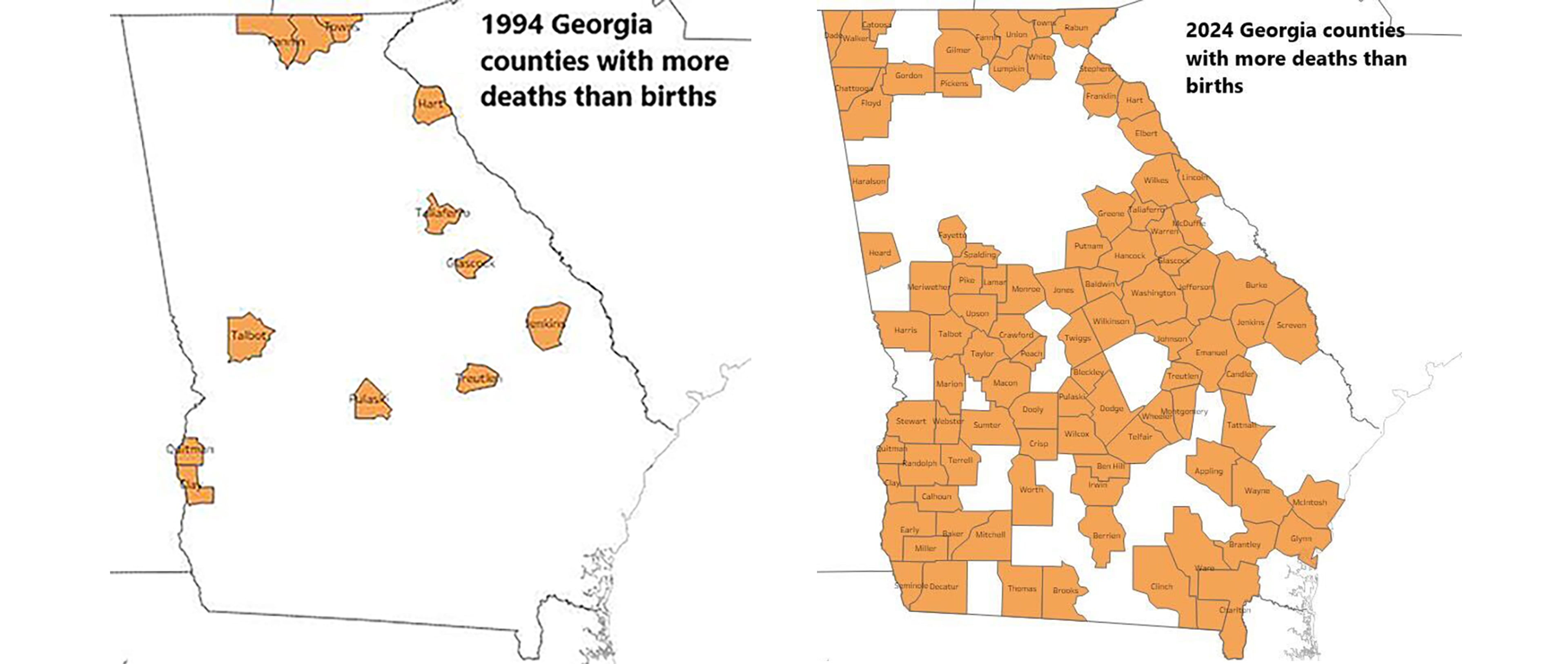

Recently, Hayslett wrote “Mapping the death of rural Georgia,” a sober piece demonstrating that concept in bleak outlines. Years ago, he started compiling state data concerning the number of births and deaths registered in each Georgia county.

In 2017, he made a presentation at the initial meeting of the Georgia House Rural Development Council, held in Tifton.

He showed legislators a map from 1994 that indicated 12 of Georgia’s 159 counties had more deaths than births. That number stayed relatively constant until after the Great Recession of 2008. Then the numbers took off.

By 2015, there were 60.

Recently, he checked again. In 2024, there were 94 counties with more deaths than births. Another 11 counties were just barely on the plus side. That means in a year or two, probably 100 of Georgia’s 159 counties will have more residents leaving the earth than arriving.

“Map the data over time and you can’t help but get the sense that you’re witnessing the spread of some kind of socioeconomic cancer consuming more and more of the state,” he wrote.

I called Hayslett, who started compiling data about rural Georgia in 2009 for a health care foundation.

Initially, he said: “I was blown away by the numbers coming in.”

Economic activity had stagnated or gone in reverse. Populations were aging and less healthy. Young families were leaving. Educational achievement was lagging. And health care providers were vanishing.

A decade ago, he wrote that Gwinnett County, with 860,000 residents, generated 22% more income and contributed 47% more in taxes than the 1.16 million residents living in South Georgia’s 56 counties combined. And it produced half as many criminals and ate up substantially less social services than South Georgians.

“You have counties aging out,” Hayslett told me. “These trends coupled with little in-migration, and you have parts of the state hollowing out.”

It’s a story seen across the country. Rural counties lose population as older residents die off and younger residents move away — or choose not to have many children.

Hayslett was not surprised that the number of counties with deaths outnumbering births was approaching 100. But, he was surprised that the number jumped so suddenly from 19 in 2009 to 60 in 2015

“You’ve got populations that are getting older and older and are no longer having children, and the people young enough to have children are deciding not to,” he told me. “It really is sort of a death spiral, literally.”

The state is beyond the point of employing conventional solutions, he said. “It’ll take something radical.”

State Rep. Gerald Greene, a Cuthbert resident with 43 years in the Legislature, knows this all too well. The Democrat-turned-Republican represents nine counties in the state’s southwest corner. Five no longer have hospitals, including his own Randolph County’s facility, which closed in 2020.

Recently, he experienced excruciating pain from a kidney stone and could not get an ambulance. “So, I got in my car and drove myself to Albany,” he said. It was 46 miles of holding onto his side and driving fast.

Eight of his nine counties had more deaths than births. Dougherty County, where Albany is, had one more birth than death and will probably be in negative territory soon.

(Not all counties with negative birth-to-death rates are shrinking. For instance, Union County in North Georgia, which registered the largest difference in deaths and births last year, grew by 15% from 2010 to 2020. It’s become a retirement haven, with more than twice as many 55- to 79-year-olds than childbearing 20- to 44-year-olds.)

Greene mentioned that Georgia-Pacific recently closed a containerboard mill in Early County, laying off more than 500 workers.

“These were good-paying jobs with skilled individuals,” he said. “Now we are faced with the continuing rural stigma of a loss of population, a loss of income and all that goes with it.”

He said NAFTA helped kill off most of the manufacturing in his district.

As the initial head of the committee overseeing rural redevelopment, Greene knows well the uphill battle his district, and hundreds like it across the country, are facing: “Problems with workforce, health care, transportation, education,” he said. “We have good schools, just finding teachers is a problem.”

Greene’s district has a new four-lane road, some broadband cable installed, a multimillion-dollar renovation to Bagby State Park and a private college in Cuthbert that is thriving again.

Rural Republican legislators are firmly in charge of the House and Senate, heading up about twice as many committees as do lawmakers from metro Atlanta.

But try as they might, they are pushing back against historic demographic tides.

As to the birth rate trend, Greene noted: “People can’t afford children. To raise a child now is a big decision. You’re looking to the future.”

And in much of rural Georgia, the future is not there.