READ: DeKalb approves text for lynching marker in Decatur Square

The DeKalb County commission on Tuesday approved the text that will be engraved on a marker in Decatur Square to recognize victims of racist lynchings in the county.

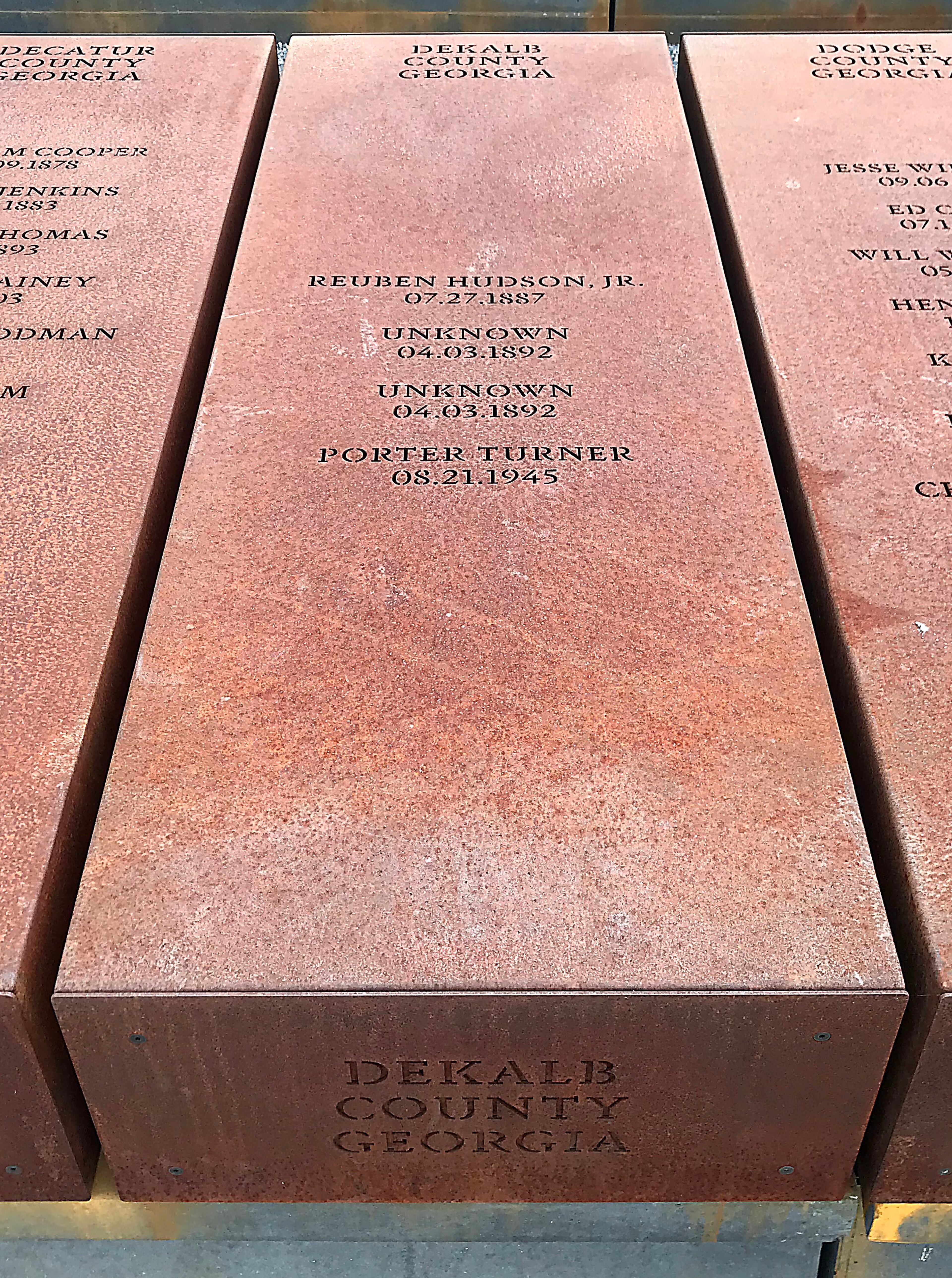

The marker represents the county’s desire to reckon with the history of racial terror in DeKalb, where the lynchings of at least four black men have been documented.

Montgomery-based organization the Equal Justice Initiative is sponsoring the marker, which officials said will be erected outside the county courthouse in downtown Decatur, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution previously reported. The language was unanimously approved at a commission meeting Tuesday.

The organization is partnering with local governments and groups across the country to place public markers that document lynchings in their communities. The group placed a marker in LaGrange in March 2017 in a ceremony where over 100 people attended, including relatives of two lynching victims. All told, 592 Georgians were lynched during the period from 1877 to 1950, the second most of any state during the Jim Crow era, according to the Equal Justice Initiative.

While discussing the measure, DeKalb Commissioner Larry Johnson recited the lyrics of “Strange Fruit,” the chilling song performed most famously by Billie Holiday that protested racism and lynchings. Johnson said the marker reflects the county’s effort to “make sure that we apologize and say we’re sorry” to victims. He said officials are working to find the victims’ family members.

DeKalb approved the placement of the marker in January. The county is believed to be just the second government entity in Georgia to acknowledge the lynchings that occurred within its borders.

Officials plan to unveil the marker on March 29, 2020, said Teresa Hardy, the president of the DeKalb County branch of the NAACP, which is working with the Equal Justice Initiative on the marker.

“I'm proud to say that we have come a long way, and by no means will we ever go back. We will continue to forge forward,” Commissioner Mereda Davis Johnson said Tuesday, acknowledging the “injustices of the past.”

Commissioner Jeff Rader said the marker is a poignant effort to “right the wrongs of the past and recognize the fundamental equality of every American.”

Members of the NAACP began working on what they call the DeKalb Remembrance Project shortly after returning from a 2018 trip to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala.

Here is the full text that the county approved for the marker:

Side 1: LYNCHING IN DEKALB COUNTY

Between 1877 and 1950, racial terror lynchings of African Americans by white mobs in DeKalb County created a climate and legacy of violence and injustice that has not been previously acknowledged in DeKalb County. On July 26, 1887, a black man named Reuben Hudson, Jr. was riding on a Georgia Railroad train when a conductor claimed that he resembled a man accused of assaulting a white woman in Redan. After the conductor turned Mr. Hudson over to local officers. He was forced to go to Redan the following day, denied a trial, seized by a mob of 100 white men and hanged from a tree. On April 3, 1892, two unknown black men disappeared near Lithonia after they were accused of assaulting a white girl and were pursued by a mob. Newspaper coverage was wide but sparse and did not include their names. The newspapers reported that when the mob returned without the men, it was "generally understood that they were lynched." On August 21, 1945, Porter Turner, a black taxi driver who served white passengers, was found stabbed to death on the lawn of a physician in Druid Hills. Officials assumed the motive was robbery. However, almost a year later, an informant revealed that members of the Kavalier Klub -- a branch of the Georgia Ku Klux Klan -- were responsible for his death. Each of these lynchings terrorized the black community, and the perpetrators of these lawless acts were not held accountable. Memorializing these known and unknown victims reminds us to remain persistent and diligent in the pursuit of justice for all.

Side 2: LYNCHING IN AMERICA

Following the Civil War, violent resistance to rights for African Americans, a need for cheap labor and an ideology of white supremacy led to fatal violence against black women, men, and children. Thousands of black people were the victims of racial terror lynching in the United States between 1877 and 1950. Lynching emerged as the most public and notorious form of racial terrorism and violence, intended to intimidate black people and enforce racial hierarchy and segregation. Many African Americans were lynched following accusations of violating social customs, engaging in interracial relationships, or committing crimes, even when there was no evidence tying the accused to any offense. African Americans accused of these alleged offenses often faced hostile suspicion and a presumption of guilt that made them vulnerable to mob violence and lynching. White mobs regularly displayed complete disregard for the legal system, seizing their victims from jails, prisons, courtrooms, or out of police hands without fear of legal repercussions. Racial terror lynchings often included burnings and mutilation, sometimes in front of crowds numbering in the thousands. In many cases, the names of lynching victims were not recorded, revealing the indifference towards the injustices committed against them. Although many victims of racial terror lynching will never be known, at least 592 racial terror lynchings have been documented in Georgia.

-- Wouldn’t you like to support our strong journalism? Your subscription helps us cover your communities in a way that no one else can. Visit https://subscribe.ajc.com/hyperlocal or call 404-526-7988 to begin or renew your subscription.