Native American leading effort to create Georgia’s first national park

MACON — Tracie Revis recently climbed to the top of a towering earthen mound that once served as a Native American chief’s home in this part of Middle Georgia. The National Park Service estimates it was built with 10 million baskets of dirt, weighing about 60 pounds each.

Called the Great Temple Mound, it rises 55 feet, offering Revis striking views of the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park and even downtown Macon. Also visible from the top are a rebuilt tribal council chamber and a vast field where athletes once competed in a sport from which lacrosse originated.

More than 100 burials have been discovered at a nearby funeral mound.

“We truly believe our spirits are still here,” Revis said.

Revis is a Muscogee (Creek) Nation citizen with Yuchi heritage, meaning the park is part of her family’s ancestral lands. So it is fitting that Revis, 48, is now leading the effort to transform the site into Georgia’s first national park and preserve. She took over as acting CEO of the Ocmulgee National Park and Preserve Initiative this year after former Macon Mayor Pro Tem Seth Clark stepped aside to run for lieutenant governor.

The nonprofit’s change in leadership comes at a pivotal time for the yearslong initiative, which could help grow and preserve the site and boost tourism and economic development in the region.

If Revis and fellow advocates are successful, the Ocmulgee site would become the nation’s 64th national park, joining such popular destinations as Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado and Yosemite National Park in California.

The effort experienced a setback in December when the Trump administration said it opposed key legislation. But Revis and her allies remain optimistic, pointing to progress in Washington, where most of Georgia’s congressional delegation is backing measures in both the House and Senate.

Revis’ nonprofit, meanwhile, has commissioned a report focusing on how the Macon region should prepare for a new national park and preserve with public infrastructure, land conservation, economic development and responsible development.

A December draft of the report says the Ocmulgee River corridor includes “hundreds of recorded cultural resource sites, but many remain unmapped, unprotected, or undocumented due to gaps in survey coverage and outdated data.”

At the same time, Revis is helping strengthen her tribe’s ties with Macon. She has taken many people from here to Oklahoma so they can learn about Muscogee people. Their capital in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, is named after their Georgia homeland. And their legislative branch operates in what is called the “Mound Building,” which represents the mounds the Muscogee people created across the Southeast before they were forced west.

“I am proud I have been able to be here during this time,” Revis said, “and to work with this community and to connect Oklahoma and Georgia back together.”

‘McIntosh, we have come!’

English settlers referred to the Muscogee-speaking people they encountered in Georgia as “Creeks” because many lived near Ochese Creek, now called the Ocmulgee River.

Calling “Creeks” a misnomer, some tribal citizens prefer to be called “Muscogee.” In 2021, the tribe announced it was removing “Creek” from its marketing materials as part of a “decolonized representation strategy,” though its official name remains “Muscogee (Creek) Nation.”

Before they were forced west, the Muscogee people were one of the largest and most powerful Native American groups in the Southeast. They controlled millions of acres in present-day Georgia, Alabama and Florida, according to the Encyclopedia of Alabama.

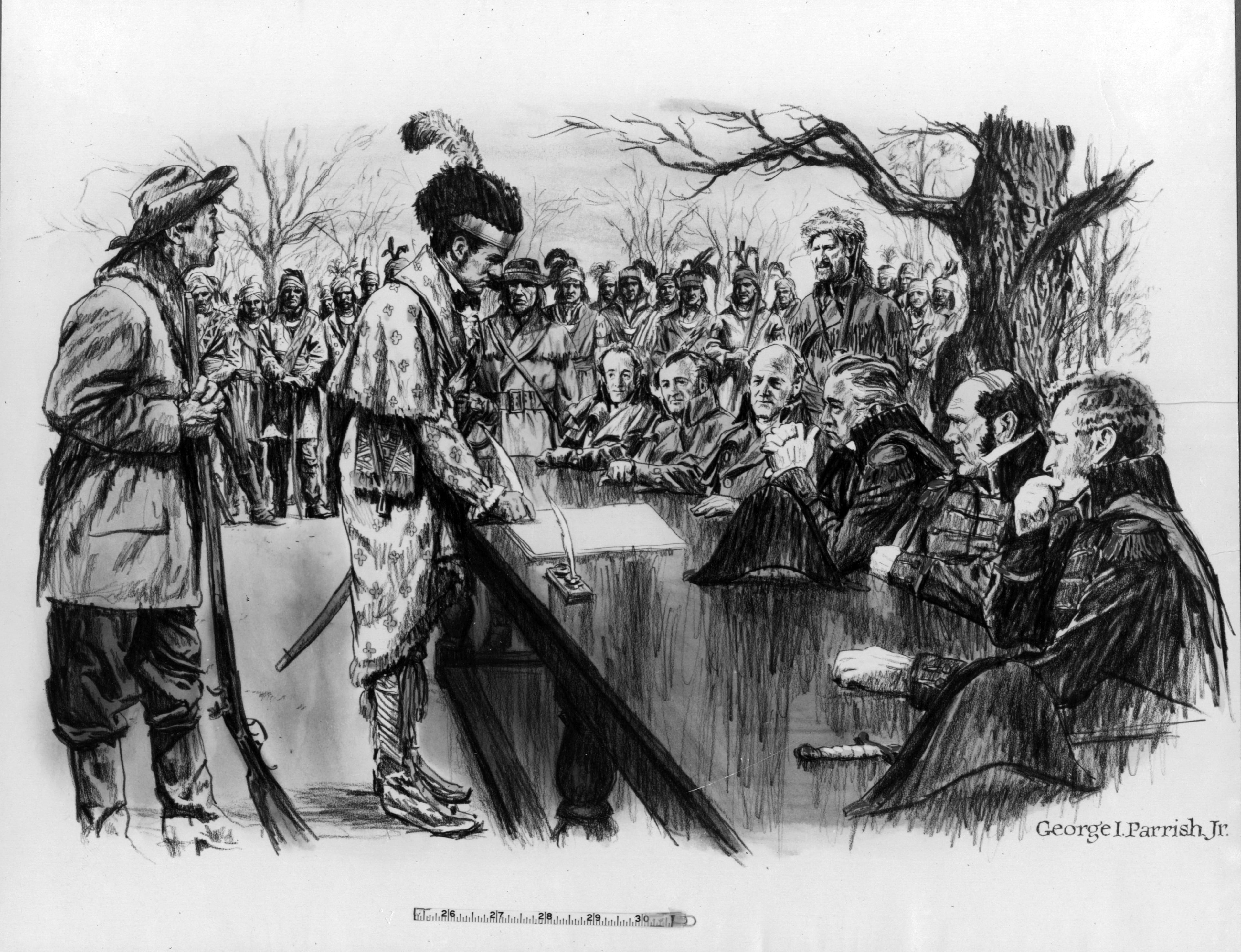

They incrementally lost their land, the encyclopedia says, through treaties with the British and American governments, land speculator scams, thefts by squatters and clandestine deals made with federal agents. One of those deals resulted in the infamous 1825 Treaty of Indian Springs.

After the Revolutionary War, many more American settlers began pouring into Georgia, coveting Muscogee land. In 1824, a pair of federal commissioners met with the Muscogee National Council, asking for more. The council declined. So the commissioners approached William McIntosh, a well-connected Native American leader who was the son of a British military officer and a Muscogee woman.

McIntosh was related to a Georgia state legislator, a federal tax collector and Gov. George Troup, who staunchly supported removing the Muscogee people from the state, according to Claudio Saunt’s 2020 National Book Award finalist, “Unworthy Republic: The Dispossession of Native Americans and the Road to Indian Territory.”

McIntosh helped Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson win the Battle of Horseshoe Bend during the Creek War of 1813-14. That victory resulted in the defeat of the Red Sticks, Muscogee people who were opposed to giving up more land. In the war’s aftermath, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, the Muscogee people lost 22 million more acres in Alabama and Georgia and suffered from famine.

In 1825, McIntosh invited the federal commissioners to a resort he owned at Indian Springs, Georgia, where he worked out a treaty with them. In exchange for $400,000 for him and his friends, McIntosh agreed to give up all Muscogee land in Georgia in addition to three million of the tribe’s acres in Alabama, according to the Encyclopedia of Alabama.

“McIntosh could not resist the temptation to exploit his position, almost always at the expense of his indigenous relatives,” Saunt wrote. “Negotiated in secret and consummated with bribes, the Treaty of Indian Springs, as it was called, lacked the signatures of the nation’s recognized leaders, with the exception of McIntosh.”

Arguing McIntosh did not have authority to give away the land, the Muscogee National Council selected a large group of warriors to execute him that year. Called the “law menders,” they were led by Menawa, a Red Stick war chief who fought against McIntosh in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend.

William Winn, a veteran journalist and historian, wrote about what happened next in “The Triumph of the Ecunnau-Nuxulgee,” his 2015 book about the forced removal of the Muscogee people: The law menders found McIntosh at Acorn Bluff, his plantation near the Chattahoochee River in what is present-day Carroll County. As they set fire to his home, they shouted: “McIntosh, we have come, we have come! We told you, if you sold the land to the Georgians, we would come!”

A gunbattle began. McIntosh barricaded his front door. Then he retreated to his second floor, where he continued firing at his attackers. No longer able to stand the flames, he reappeared at the entrance to his home and then fell as bullets ripped through him. The raiding party dragged him by his heels into his front yard, where Menawa plunged a knife deep into his heart.

In 1826, President John Quincy Adams’ administration declared the treaty McIntosh agreed to at Indian Springs “null and void” and signed a new agreement with the Muscogee people for their land.

A year later, the forced removal of 23,000 Muscogee people began, requiring them to travel for months across hundreds of miles, according to the National Museum of the American Indian. Cherokee people living in North Georgia were also forced west in the ensuing years, in what came to be known as the Trail of Tears. Thousands of Cherokee and Muscogee people died on the way or soon after they arrived in what is now Oklahoma.

Trump administration opposition

In 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Ocmulgee National Monument. The government’s Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration built the park’s roads and trails and reconstructed the Muscogee earthen council chambers that once stood there.

During an archaeological dig in the 1930s, 2.5 million artifacts were discovered at the park, including pottery, arrowheads, stone tools, pipes and jewelry. Those findings helped researchers piece together a timeline of people who lived on the Macon Plateau between 12,000 B.C.E. and 1800 C.E.

“We are an ancient civilization,” Revis said. “People travel all over the world to see civilizations that are 200 years old. Why would we not want to share what we have here?”

In 2019, President Donald Trump signed legislation transforming the monument into the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park. It now includes about 3,300 acres and features eight miles of nature trails as well as a visitor center with a gift shop and museum. Bright yellow signs posted along the trails warn of alligators.

During the Biden administration in 2024, the National Park Service said it supported the intent of legislation for turning the site into a national park and preserve. A national park designation, granted to only 63 other sites in the U.S., could further elevate the site’s status and draw more tourists and funding. But the bill stalled, as did similar legislation in the House.

Last year, U.S. Sen. Jon Ossoff, fellow Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock and all but one of Georgia’s 14 House members signed onto similar bills in both chambers. Still pending in committees, those measures have drawn support from the tribe as well as the Georgia Chamber of Commerce and the Greater Macon Chamber of Commerce.

The bills would authorize the federal government to acquire additional land for the project and create an advisory council for helping plan its future. Three representatives from the Muscogee tribe would serve on the seven-member panel.

Creating a national park could increase visitors to the area by 1.1 million, support an additional 2,814 jobs and add $206.7 million in annual economic activity, according to a 2017 report commissioned by the National Parks Conservation Association.

During a Dec. 9 Senate subcommittee hearing on Capitol Hill, though, National Park Service Associate Director Mike Caldwell said his agency opposed Ossoff’s legislation and other bills on the panel’s agenda that day because they “would establish or expand NPS units or direct new studies, all of which would require additional resources.” Caldwell added: “The NPS remains focused on addressing critical needs within its existing portfolio.”

It’s unclear what the Senate bill would cost taxpayers. It says only that it would authorize the appropriation of “such sums as are necessary.” The same language is in the House version.

Ossoff said he was disappointed by the Trump administration’s “sudden and inexplicable reversal of longstanding National Park Service support for Ocmulgee Mounds.” He and U.S. Rep. Austin Scott, R-Tifton, vowed to press on with their bills.

“The Ocmulgee mounds are of valuable cultural, communal, and economic significance to our state,” Scott said in a statement. “For these reasons, I am committed to keeping this initiative moving forward.”

Muscogee Principal Chief David Hill said he remains hopeful. Creating the national park and preserve in Georgia, he said, would help showcase the history of “the original place that we call home.”

“We just want to share our true history of who we are,” said Hill, who is based in Oklahoma. “I am just hoping and praying that the ancestors above are looking down to see it to fruition.”

‘I go where I feel like I am called’

Revis, who previously served as Hill’s chief of staff, moved from Oklahoma to Macon four years ago so she could begin work as the advocacy director for the Ocmulgee Mounds National Park and Preserve Initiative.

The nonprofit describes itself as a group of Middle Georgia and Muscogee citizens focused on local conservation. With grant funding from the Knight Foundation, the initiative is collaborating with the Middle Georgia Regional Commission on plans for the proposed national park.

Much of Revis’ efforts have focused on strengthening ties between Georgia and her tribe. During a recent tour of Macon, she visited a historic house near the Ocmulgee mounds that local officials are planning to transform into a new Muscogee cultural center. Her tribe’s flag flies beside City Hall. And many of Macon’s street signs feature English and Muscogee words.

Revis is the daughter of a law enforcement officer and a nurse who met while serving in the U.S. Marine Corps in Washington. Her family moved often before settling in Tulsa, where she graduated from high school.

Later, she interned for Democratic U.S. Rep. Raúl Grijalva of Arizona, became an attorney and served as the acting Muscogee tribal administrator. The tribe bills itself as the fourth largest in the nation with 103,000 citizens.

Revis emphasized she felt compelled to move to Georgia in 2022 so she could begin her advocacy.

“I feel like I was brought back here,” she said. “I was raised very spiritually and traditionally. I go where I feel like I am called.”