FDA will remove long-standing warning from hormone-based menopause drugs, citing benefits for women

WASHINGTON (AP) — Hormone-based drugs used to treat hot flashes and other menopause symptoms will no longer carry a bold warning label about stroke, heart attack, dementia and other serious risks, the Food and Drug Administration announced Monday.

U.S. health officials said they will remove the boxed warning from more than 20 pills, patches and creams containing hormones like estrogen and progestin, which are approved to ease disruptive symptoms like night sweats.

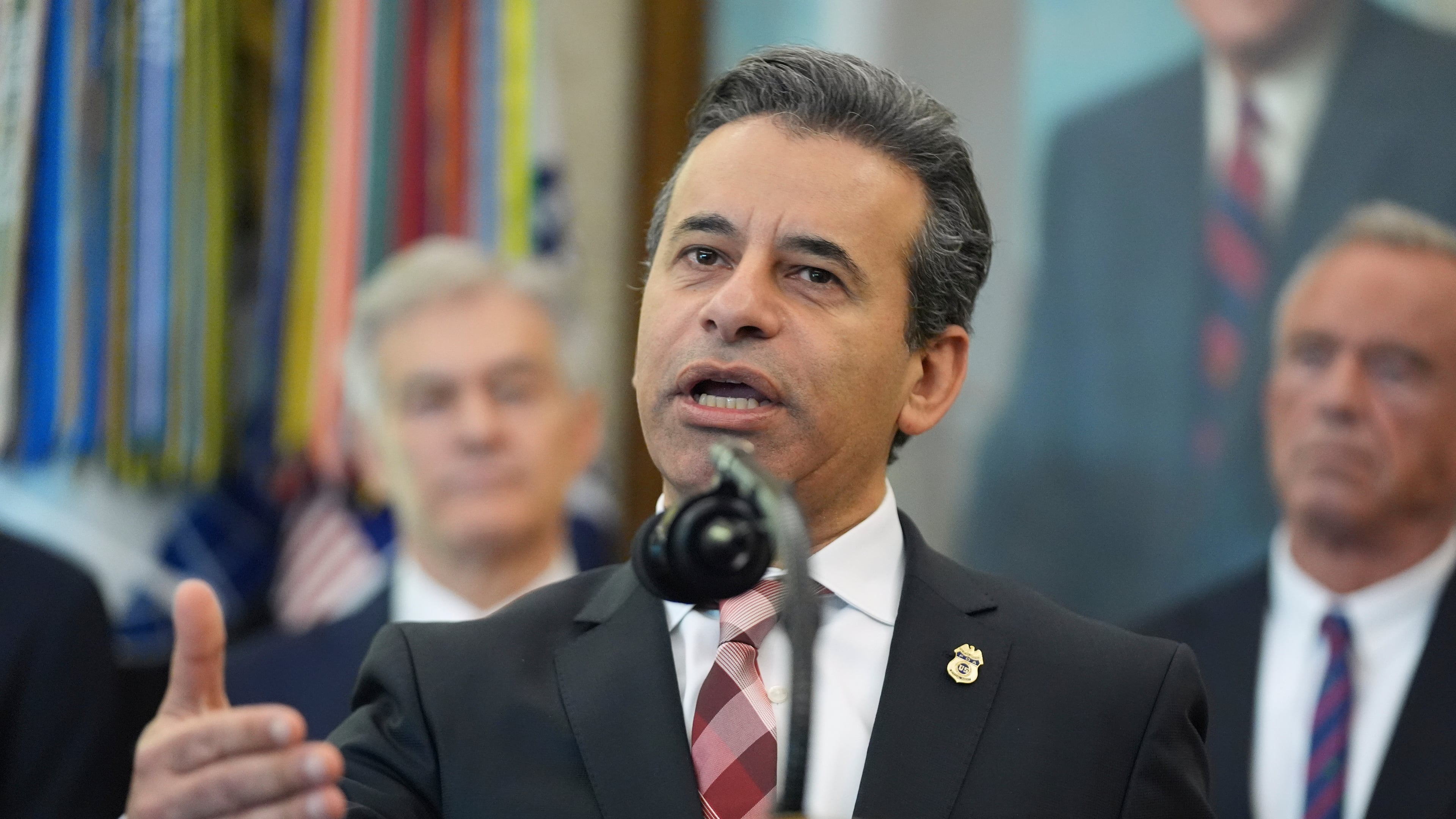

The change has been supported by some doctors — including FDA Commissioner Marty Makary, who has called the current label outdated and unnecessary.

The long-standing FDA warning advised doctors that hormone therapy can increase the risk of blood clots, heart problems and other health issues, citing data published more than 20 years ago.

Many doctors — and pharmaceutical companies — have called for removing or revising the label, which they say discourages prescriptions and scares off women who could benefit.

But other experts have vigorously opposed making changes to the label without a careful, transparent process. They say the FDA should have convened its independent advisers to publicly consider any revisions.

Current medical guidelines generally recommend the drugs for a limited duration in younger women going through early or mid-stage menopause who don’t have complicating risks, such as breast cancer or heart problems. FDA’s updated prescribing information mostly matches that approach.

But Makary and some other doctors have suggested that hormone therapy’s benefits can go far beyond managing uncomfortable mid-life symptoms. Before becoming FDA commissioner, Makary dedicated the first chapter of his most recent book to extolling the overall benefits of hormone therapy and criticizing doctors unwilling to prescribe it.

In the 1990s, millions of U.S. women took estrogen alone or in combination with progestin on the assumption that — in addition to treating menopause — it would reduce rates of heart disease, dementia and other issues.

But a landmark study of more than 26,000 women upended that idea, linking two different types of hormone pills to higher rates of stroke, blood clots, breast cancer and other serious risks. After the initial findings were published in 2002, prescriptions plummeted among women of all age groups, including those in earlier stages of menopause.

Since then, all estrogen drugs have carried the FDA’s boxed warning — the most serious type. National health data shows prescribing of the drugs has not increased over the last 20 years.

But continuing analysis has shown a more nuanced picture of the risks.

A new analysis of the 2002 data published in September found that women in their 50s taking estrogen-based drugs faced no increased risk of heart problems, whereas women in their 70s did. The data was unclear for women in their 60s, and the authors advised caution.

Additionally, many newer forms of the drugs have been introduced since the early 2000s, including vaginal creams, rings and tablets which deliver lower hormone doses than pills, patches and other drugs that circulate throughout the bloodstream. Those products will receive their own label, reflecting their unique risks and benefits, the agency said.

The original language contained in the boxed warning will still be available to prescribers, but it will appear lower down in the prescribing information. Additionally the label will retain a boxed warning that women who have not had a hysterectomy should receive a combination of estrogen-progestin due to risks of cancer in the lining of the uterus.

Hanging over Monday’s announcement is the way the agency laid the groundwork for the decision.

Rather than convening one of the agency’s standing advisory committees on women’s health or drug safety, Makary earlier this year invited a dozen doctors and researchers who overwhelmingly supported the health benefits of hormone-replacement drugs.

Many of the panelists invited to the July meeting consult for drugmakers or prescribe the medications in their private practices. Some also had ties to a pharmaceutical-sponsored campaign called Unboxing Menopause, which lobbied the FDA to remove the warning.

Nearly 80 researchers later sent a letter to the FDA calling for an official advisory committee meeting.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.