From death threats to musical tribute: 1st openly gay bishop to be honored Pride Sunday

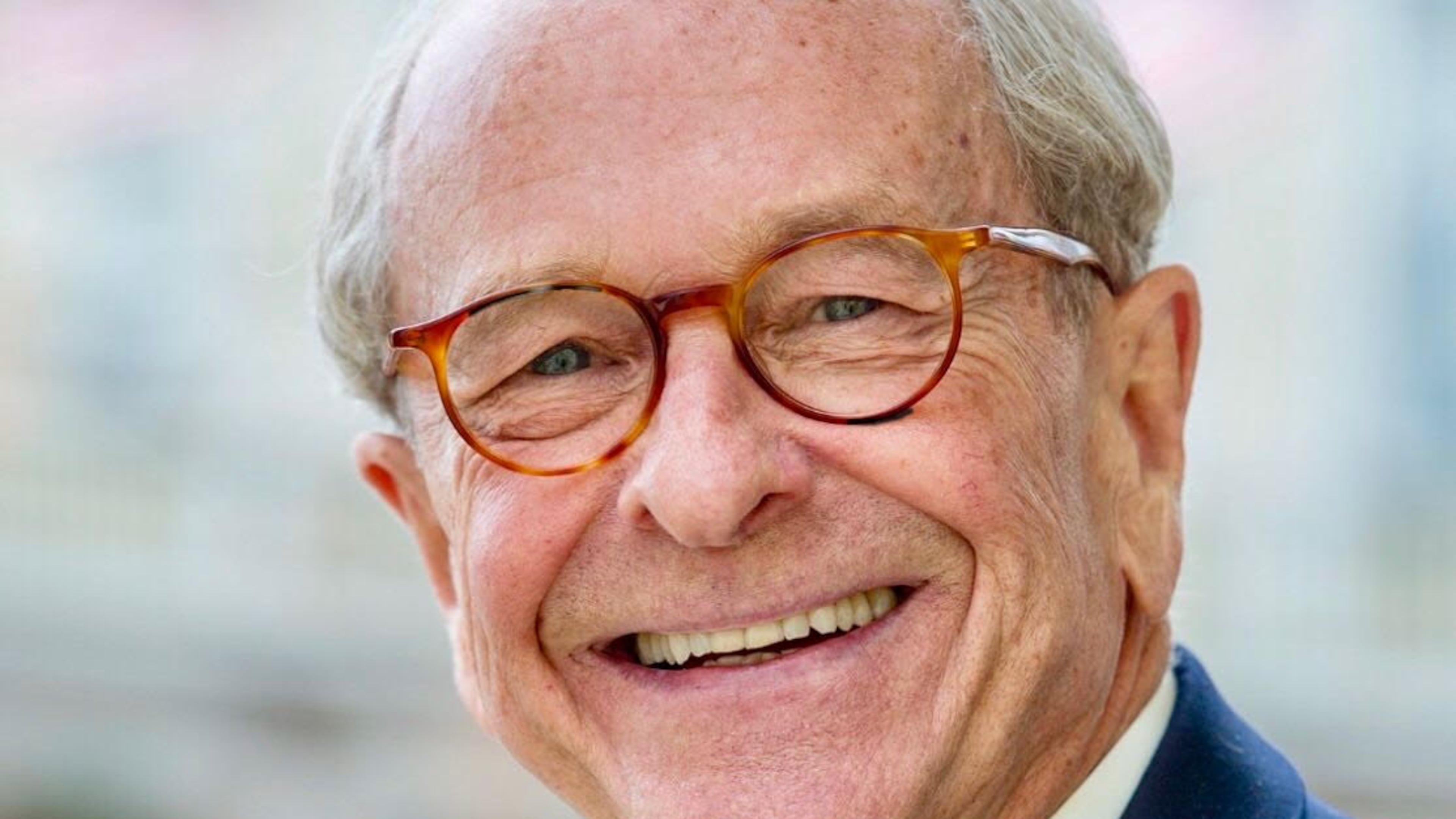

On the day in 2003 that Gene Robinson was to be consecrated as the first openly gay bishop in any historic Christian denomination in the world, he wore a bulletproof vest underneath his regal vestments.

Robinson — who will be speak and be honored at Atlanta’s St. Luke’s Episcopal Church on Pride Sunday — was instructed on what to do if a bomb went off or shots were fired. If he was still alive, he was to be ushered out of the sanctuary by a small group who would proceed with his consecration.

No bomb went off. No shots were fired. But the storm wasn’t over.

Early Years

Eighteen years earlier, when Gene Robinson came out as a gay man in 1986, he had already been married to his wife Isabella for 14 years. They had two young daughters. He had been a church leader since they met at the University of Vermont, when she was a student, and he was interning as an Episcopal chaplain.

He had been up front with her about his relationship history. He told her all his previous romantic partners had been men. He admitted he had gotten therapy to make heterosexuality work because he desperately wanted a family.

A few months before their wedding, he told her he was afraid.

“I said to her, ‘I’m just scared this thing is going to rear its ugly head.’” Robinson recalls. “She said, ‘If that happens, we love each other enough. We will find a way.’”

At the time Robinson came out, the world was not a pleasant place for gay men.

“Not only were gay men dropping dead by the thousands in the AIDS crisis, but there was little positivity toward gay people,” he remembers. “I knew my life in the church was over (if I came out). I had no doubt about that.”

Robinson and his wife told their two daughters together. She could have taken full custody of their daughters, but she didn’t.

“We were both needing and wanting (the divorce), even though it was incredibly painful,” Robinson said.

As painful as that was, it paled in comparison to what would come 18 years later.

Becoming Bishop

In June 2003, Robinson was put up for election by the Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire to become bishop.

His life in the church had not ended in 1986 as expected. Rather, a few months after he came out to his bishop, he was offered a job as Canon to the Ordinary, or chief assistant to the bishop.

Robinson spent 18 years faithfully serving under his predecessor. Most of New Hampshire’s laity (lay church community) came to know him, he said, as a warm-hearted, witty and empathetic man whose identity as a gay man came second to who he was a person.

He earned the required two-thirds majority vote from both clergy and the laity to become bishop.

“I got my first death threat that day,” Robinson said.

Almost every week that followed, for almost three years, Robinson received a threat from somewhere. Some came in the form of phone messages. Others as letters.

“I even got some, like the 1930s mysteries, where the killer cuts out letters out of a newspaper and glues them on,” Robinson recalls.

A bomb threat targeted his church. The FBI got involved.

His ordination was approved at the Episcopal Church’s General Convention in Minneapolis in November 2003, but “the storm didn’t stop,” he said.

The Archbishop of Nigeria said that “gay people are lower than the dogs,” Robinson recalled.

The Archbishop of Kenya said that the day Gene Robinson was ordained was the day Satan entered the church.

One faction of the Anglican Church even split in protest.

Robinson was forced to live a very fractured life. In his full-time role running the diocese of New Hampshire, “I had the typical life of a bishop,” Robinson said. “The minute I left New Hampshire, I became this other thing.”

He was interviewed on major media around the globe. He did four interviews with NPR’s Terri Gross. He spoke at a dinner of 3,000 guests in Dallas.

“I never knew when I got up to speak whether I was going to be assassinated or not,” he said.

Throughout it all, Robinson said, he was deepening his understanding of how God’s “power is made perfect in weakness.” He leaned heavily on the writings of David in Psalm 27: “The Lord is my light and my salvation; whom shall I fear?”

He came to deeply believe, Robinson said, that God loved him “beyond his wildest imagining.”

‘I felt like there was hope’

In a New Hampshire town in 2002, a young, gay musician by the name of Dominick DiOrio was struggling with his faith. DiOrio grew up Catholic. He was not sure there was a place for him in any form of Christian faith.

DiOrio left for college that year as “a pale reflection of my inner self,” he said, not sure if he should continue to spend his life that way, or if there was a way he “could exist in true color.”

In 2003, he remembers seeing Robinson’s election as the first openly gay bishop.

“I felt like there was hope,” DiOrio recalls. “If one of the major Christian denominations in the world could welcome (Robinson) as a faith leader, surely there were paths for my own life that I had not yet imagined.”

Twenty-one years later, while working as a professional conductor, composer and professor of music at Indiana University, DiOrio was approached by a friend, Michael Pettry, about writing a commissioned piece of music for a consortium of Episcopal churches across the U.S. The music was to be a tribute to Bishop Gene Robinson.

Pettry did not know DiOrio’s personal connection to the bishop, nor that DiOrio grew up in the New Hampshire town next door to Robinson’s parish. The ask felt fated.

“I said yes almost immediately,” said DiOrio. He got to work composing a score.

Robinson was asked to select quotations from his years of sermons to be incorporated as lyrics, but the task proved too difficult.

“It’s like having to say which child of yours is your favorite,” Robinson said. “I was the last person in the world who could do it.”

Instead, DiOrio volunteered to mine Robinson’s words for lyrics. He devoured media featuring Robinson, including two documentaries, two books and dozens of sermons.

“That was honestly harder than writing the music,” DiOrio said. “I wanted to, of course, give honor to everything he had done, but also try and find his spirit, his personality.”

A phrase kept surfacing: “beyond our wildest imagining.”

“Those words were present in a lot of different things,” DiOrio said. “So, I took that as the kernel to begin.”

“Our Wildest Imagining” eventually became the title of DiOrio’s musical composition.

‘Beyond your wildest imagining’

For decades, Robinson’s two daughters and two granddaughters would lovingly tease him about his favorite saying: “God loves you beyond your wildest imagining.”

“On Christmas cards and birthday cards, they would write ‘Daddy, we love you beyond your wildest imagining,’” Robinson said.

When DiOrio’s musical composition came to his email inbox for the first time, Robinson was stunned and moved to tears when he saw the title: “Our Wildest Imagining.”

“It feels really personal and I own every bit of it,” Robinson said.

One lyric in DiOrio’s libretto also stood out as a summation of Robinson’s journey: “When one is certain of God’s love, there is no end to what one can bear.”

The lyric echoed Psalm 27.

Through the years, as reporters and community members have asked Robinson about how he survived and if he would go through it again, his answer comes easy: “Absolutely.”

“In going through it, I learned so much about God’s love and my relationship with God,” he said. “How could you say no to that? It’s the truest thing I’ve learned in all of this.”

The musical premiere

Robinson’s path paved the way for Atlanta couples like longtime St. Luke Episcopal Church members Elaine DeCostanzo and Annabeth Balance who were the first couple to ever receive a same-sex blessing ritual at their church in 2013 before same-sex marriage was legalized in Georgia in 2015.

DeCostanzo remembers watching Robinson’s election as Bishop. She was moved, she said, after having felt shut out of religion as a young woman.

“I left the Catholic Church in 1973 and didn’t darken a church door for a long time after that,” she said. “When I finally walked into St. Luke’s, I found this incredibly welcoming community … (Robinson’s) message has continued to be such a combination of strength and gentleness.”

Robinson is visiting St. Luke’s for the second time; he spoke at the church in 2014.

DiOrio’s musical tribute to Robinson, “Our Wildest Imagining,” will be performed by a 45-member choir, brass quintet and Atlanta organist Jonathan Easter at St. Luke’s during its Pride Sunday Eucharist on Sunday.

The church is one of only 10 in the U.S. that will get to premiere the music.

“It’s a huge honor to not only present a newly commissioned piece of music — that’s such a huge honor — but to have words spoken by someone who’s been hugely influential in my own life … it is just really extraordinary,” said Matthew Brown, a gay man and director of music at St. Luke’s Atlanta.

Prior to the service, at 9 a.m., Robinson will take part in a public forum with the Rev. Michael S. White, the church’s interim rector, in Budd Hall.

Following the Eucharist, Robinson and members of the St. Luke’s community, including DeCostanzo and her wife, will move to the front steps of the church, which sits directly along Atlanta’s Pride Parade route on Peachtree Street, to hand out water bottles to parade participants.

“Our Wildest Imagining” has the perfect tone for the day, Brown said.

“It’s very heroic and celebratory, magisterial and majestic, very proud,” Brown added. It’s almost like, look at what we’ve accomplished.”

If you go

“Our Wildest Imagining.” 10 a.m. Sunday in the sanctuary of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, 435 Peachtree St NE, Atlanta. Prior to the performance, at 9 a.m. Bishop Gene Robinson will give a talk in Budd Hall. Pride parade celebrations follow. stlukesatlanta.org.

Virtual gatherings. Parties who miss the Pride Sunday events will have two more opportunities to connect with Bishop Robinson and DiOrio virtually from 3-4 p.m. Nov. 20, and 4-5 p.m. Nov. 21.