Son of Tech legend, Al Ciraldo Jr. has enriched Jackets broadcasts for 50 years

It was November 1975 when Georgia Tech broadcasting legend Al Ciraldo Sr. called upon his son Al Jr. with an urgent duty to carry out and, in so doing, opened a path Al Jr. has not stopped walking.

The son was a 16-year-old junior at Lakeside High. He had been helping out in the Grant Field (now Bobby Dodd Stadium) press box at Tech football games by running the out-of-town scores from the radio booth (received from the radio station WGST, long before fans had easy access to scores while at games) to the public address announcer. But now, with spotter Russ Mills’ health having taken a downturn, Al Jr. was pressed into action, taking on the job of identifying key players involved in each play to his broadcaster father as he called the action to his audience.

“When (Mills) took ill, Dad said, ‘Listen, I’m going to need you to do this game,’” Ciraldo Jr. said last week.

That was 50 years ago. He continued to fill in for the 1976 and 1977 Yellow Jackets seasons, became a full-time spotter in 1978 and has happily spent autumn Saturdays in the press box at Bobby Dodd Stadium and in radio booths across the Southeast (and beyond) ever since, serving a stream of Tech voices and Jackets fans everywhere.

“When you have a good spotter, it makes a world of difference,” said Tech Sports Hall of Fame announcer Wes Durham, who called Tech games from 1995-2013. “And Al Jr. is terrific.”

This is a celebration and acknowledgment of a Tech graduate who has helped deliver the excitement and information of Jackets football games to the masses, and who has excelled behind the scenes as he followed a father who personified those broadcasts.

“He has covered the hides of five decades’ worth of Georgia Tech play-by-play guys, in that sense,” Tech voice Andy Demetra said.

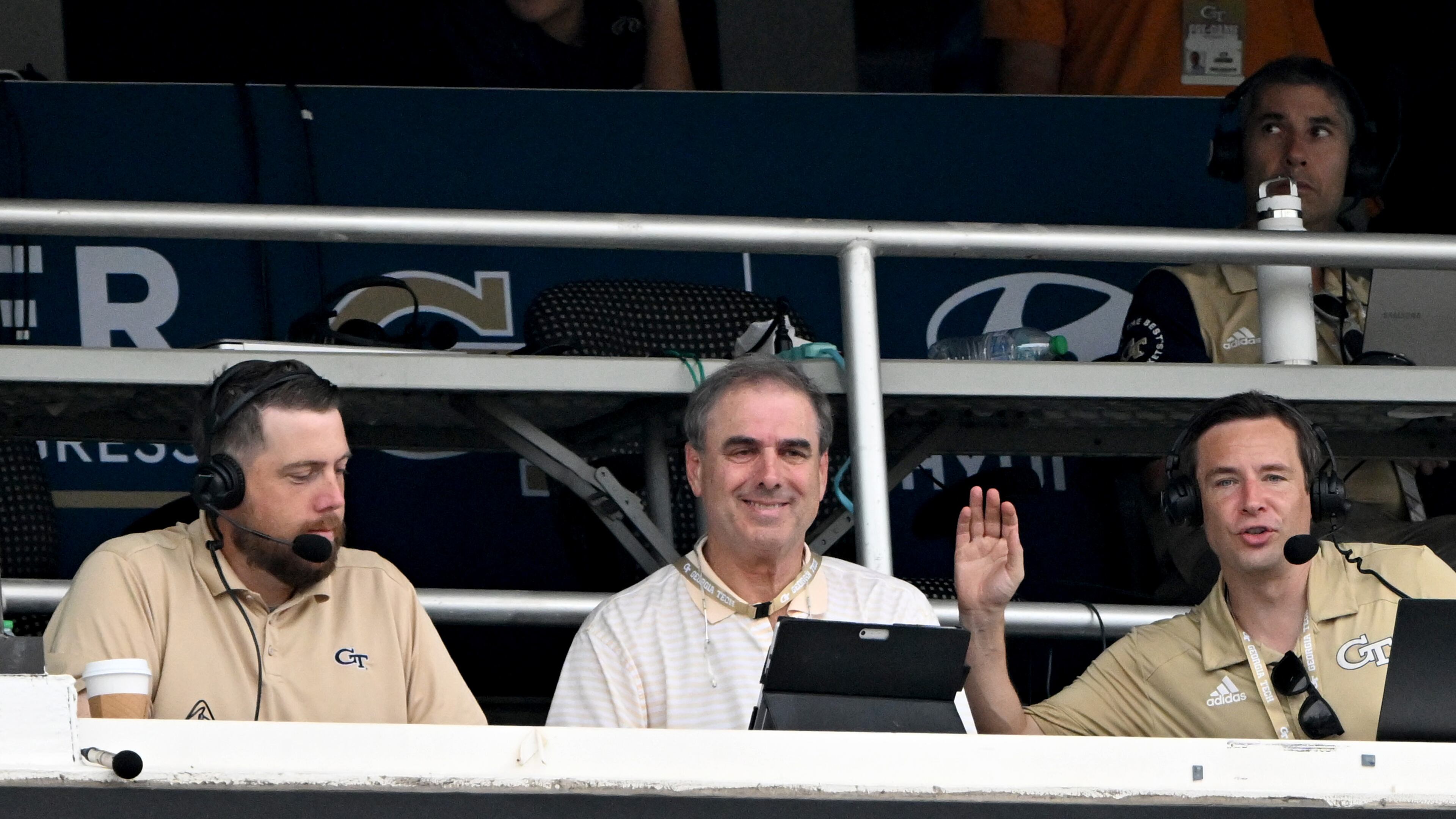

For Tech’s game Saturday against Gardner-Webb, the 65-year-old Ciraldo sat at the right of Demetra in the home-team radio booth — named in honor of Ciraldo’s legendary father, a beloved Tech Hall of Famer whose name also hangs on a banner at McCamish Pavilion — in the Bobby Dodd Stadium press box,

The other spotter, Adam Prather — a 2018 Tech graduate who was a manager for the men’s basketball team — sat on Demetra’s left, handling identification duties for Gardner-Webb. To Ciraldo’s right was analyst Andrew Gardner, the Tech Hall of Famer offensive lineman whose blocks Ciraldo once identified for Durham in his career from 2005-08.

The basics of a spotter’s job are fairly simple and largely unchanged since Ciraldo began helping his father half a century ago this fall.

Ciraldo’s main tools were his Bushnell binoculars and a double-sided chart laid out on the desk. It contained the names and numbers of Tech offensive players on one side (sorted by position) and defensive players (ordered numerically) on the other.

His primary job was to watch the action through his binoculars and put his finger on the name of the ball carrier or pass target when Tech had the ball and to similarly identify the Yellow Jackets tackler when the Jackets were on defense. (Audible communication is a no-no, as it can be picked up on the broadcast.) Between plays, he scribbled down statistics to offer to Demetra and Gardner later.

It might seem fairly easy, but the action happens quickly, and accuracy is paramount. From the press box, the field is a long way to instantly and correctly identify quickly moving athletes who may have their jersey numbers obscured by other players or the ground. Play-by-play callers typically don’t use binoculars, wanting to absorb the whole play.

When a play-by-play announcer quickly identifies a defender in on the action, “90% of the time, that’s because their spotter is on top of it faster than they are,” said former Tech voice Brandon Gaudin, now calling Braves games for FanDuel Sports Network. “And that was the case working with Al Ciraldo.”

Ciraldo also used different hand signals to point out Tech players who deflected passes, put pressure on the opposing quarterback or broke up a pass, among other actions. He also noted when players subbed in and out, enabling a mention that his father liked to incorporate to give as many players as possible a spot in the broadcast.

As he described the action, Demetra quickly peeked at Ciraldo’s signal, seamlessly working the identifications into his call.

“We’ve developed this kind of sixth sense of what I’m looking for that he knows I need and that just comes with somebody who’s done it for so long at such a high level,” Demetra said.

Special-teams plays — when both offensive and defensive players can be on the field at the same time — and players wearing duplicate numbers can make instant identifications more challenging. But in one play that involved both those complexities — a blocked Gardner-Webb field-goal try returned by a Jackets player who shares his No. 3 jersey number with a teammate — Ciraldo was on target, pointing to his name for Demetra’s benefit before he even crossed the goal line.

“Who is it?” asked Demetra, dramatically setting up his answer. “It’s Ahmari Harvey with the score!”

At the same time, both the ESPN broadcast and the stadium public-address announcer misidentified the player as Tech’s other No. 3, Eric Rivers.

Said Demetra after the game, “Al was on top of it as he always is.”

Beyond that, he fed Demetra and Gardner a variety of statistics and facts, depending on statistics he charted, the team’s game notes and his own memory. He either scribbled them down on a notepad or waited until a break in action to pass them along.

It’s a job that requires virtues that Ciraldo’s alma mater (1982, industrial management) reveres — preparation, attention to detail and facility with numbers.

It also is a job that requires a bit of humility and a willingness to be happy in the background. That’s Ciraldo.

“For someone whose dad was a legend, it would be easy to kind of make sure that people knew who you were,” Gaudin said. “He didn’t care about that at all. He just wanted to be a part of the team.”

At the game, Ciraldo sat in the same spot in the same radio booth that he has occupied for decades, between the play-by-play man and analyst. At once, he was both a long way and barely removed from the days when he first worked for his father by running scores to the PA announcer. He was an impressionable 10-year-old the first time his father brought him to the radio booth of what was then Grant Field for the Georgia game in 1969.

“Tech upset ’em 6-0,” Ciraldo said. “And it was (Tech defensive tackle) Rock Perdoni and (quarterback) Jack Williams. He interviewed Gov. (Jimmy) Carter at halftime. I just thought, ‘This is the neatest damn thing in the world.’”

Ciraldo’s long memory of Tech football has enriched broadcasts. More than a quarter century after it happened, Durham still remembers the iconic 1999 Tech win over Georgia, when Luke Manget made the game-winning field goal. He knocked it through after his first attempt, cleverly tried by coach George O’Leary on third down in the event it was blocked and recovered by Tech, was indeed blocked and recovered by Tech. In the pandemonium, Ciraldo reminded Durham that Dodd himself often used the same ploy, a priceless nugget which he shared with the audience.

“He’s terrific,” Durham said. “And, now, a really valuable resource as to everything that’s happened. Because, historically, he can speak to things that, in all honesty, not many people can.”

As a full-time spotter, he has been a part of broadcasts of more than 500 games. The Tech people he has interacted with range from Chip Robert, a successful businessman and politician who played for John Heisman in the first decade of the 1900s and was a longtime program supporter, to Prather, his fellow spotter, born more than a century after Robert.

If he hasn’t witnessed the most Jackets games in person of anyone in the team’s history — well over 500, including games he attended prior to becoming a spotter — he’s probably second behind Dodd, who was an assistant coach, head coach or athletic director for 490 games before serving as a consultant to the Tech alumni association during the final 12 years of his life. Ciraldo’s father, whose Tech career spanned from 1954 to 1997, called 416 games and more than 1,000 basketball games.

Ciraldo’s favorite game of all-time is Tech’s upset of then-No. 1 Virginia in Charlottesville in 1990, the pivotal victory in the Jackets’ surprise march to a share of the national championship. With the Tech coaches box nearby, he vividly remembers overhearing offensive coordinator Ralph Friedgen release his frustrations with multiple communications breakdowns with the coaches on the field.

Said Ciraldo, “He conjugated some irregular verbs that you couldn’t believe.”

From the time he began as a spotter, he has graduated from Lakeside and Tech, fulfilled a career in commercial real estate, gotten married (Denise, now together 33 years), raised two sons (Al III, or A.J., and Matthew) and lost both his parents.

And he has remained steadfast to an avocation he has no plans to leave, bringing to the masses the details of a team whose victories have sometimes brought him to tears. He loved working with his father — “not many kids get a chance to work with their dad” — but also being around people he has enjoyed and who have shared his passion, like the late Kim King (the Tech quarterback forever known as “The Young Left-hander,” a moniker given by Ciraldo Sr.), former longtime spotter Tommy Barber and many others.

“The thing you enjoy most is following Georgia Tech and being around the people,” Ciraldo said. “You wouldn’t do it if the people you worked with weren’t fun to work with.”

There are a multitude of ways that we can engage our love for college football. A tip of the cap to someone who found his method early on and has received and given for a half century, one wordless identification at a time.