Torpy at Large: Even arugula can’t offset the ills of gerrymandering

I took one of those Facebook personality tests the other day to rank my political leanings: I’m a left-leaning centrist, 55 percent lib/45 percent right.

The test, I figure, ranked me a bit left because I said I liked arugula.

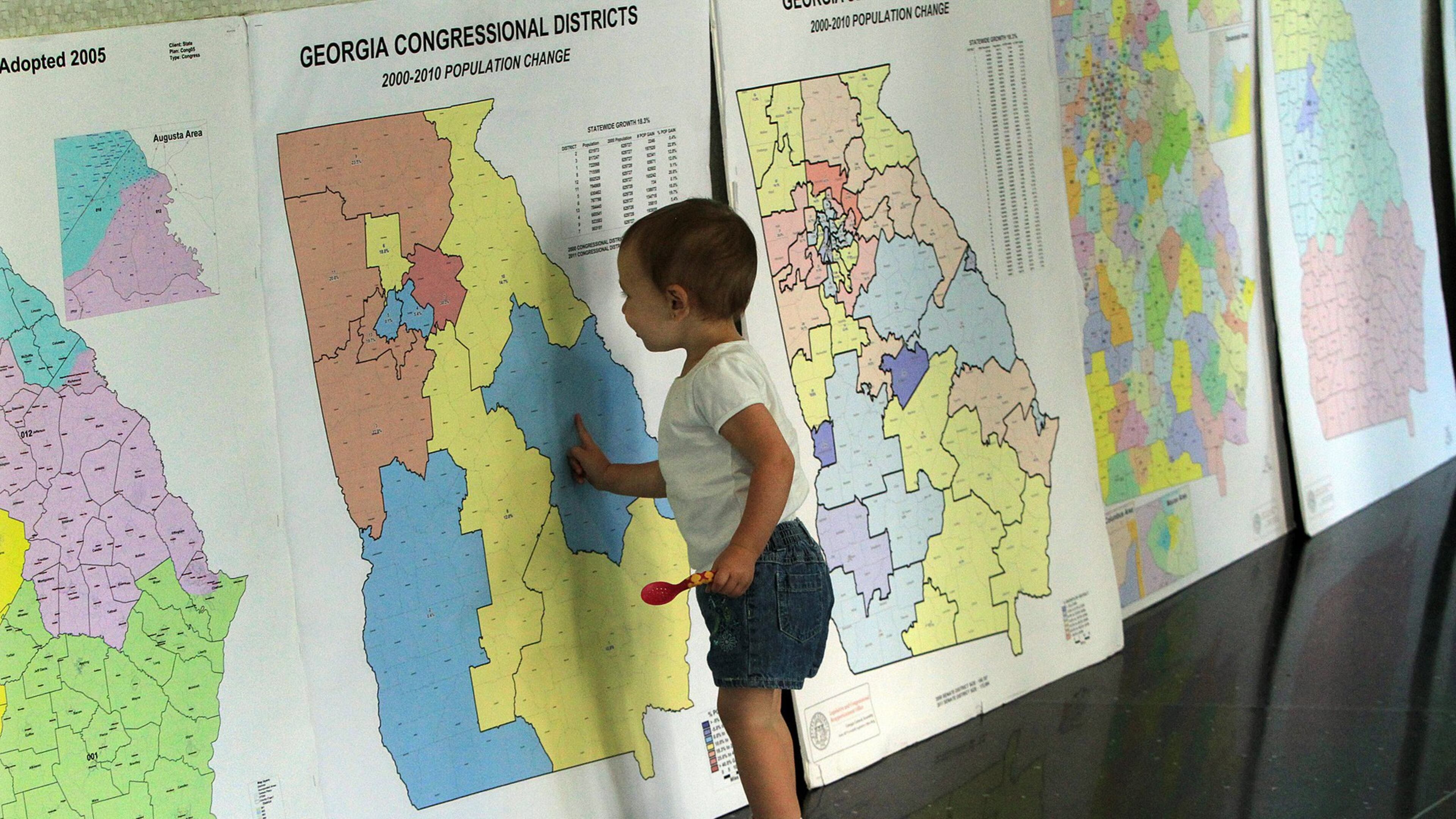

I bring this up because a couple of hours after taking this quiz, I attended a Georgia legislative committee meeting concerning an effort to remove partisanship from the redistricting process. If you know anything about how districts are drawn, there are few voting choices remaining for anyone who even thinks about being moderate in their views. Districts are often carved out to favor candidates who are either knuckle-dragging right or fist-waving left.

A resolution, pushed by a couple of longtime Democratic state representatives, Pat Gardner and Mary Margaret Oliver, calls for a constitutional amendment prohibiting political bias in drawing up state legislative and congressional maps after the 2020 census. The plan would create an "independent bipartisan" committee to draw up those districts.

Of course, as sensible as this sounds, it also seems pretty pie-in-the-sky, right? Pols have forever used gerrymandering to reward friends, punish enemies and consolidate power. It's as American as a Big Mac with a 44-ounce Coke.

"They know it's a good idea," said Rep. Gardner, who's from Atlanta, referring to Republicans. In fact, this idea is similar to proposals Republicans trotted out years ago, she said.

Yes, that was back when Republicans were a downtrodden minority wailing in the wilderness. You know, like Dems are these days.

“Only five or six districts are truly competitive,” Gardner told the House Reapportionment Committee, which is, naturally, headed by a Republican. The five or six competitive districts are out of the 236 state House and Senate districts. Once again, that’s five or six out of 236! Oddly, that’s getting better. A bit. But we’ll get back to that later.

Political gerrymandering cases in Wisconsin, North Carolina and Maryland have gone to or will be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court. The first two states are examples of Republicans misbehaving. The third is the Dems.

Like many other observers, Rep. Oliver, who's from Decatur, believes the over-the-top use of politics in redistricting will be toned down by the high court and that independent commissions will be used by more states. Gardner's proposal creates a 14-member committee — five Dems, five Republicans and four independents.

“It’s a healthier election when more moderate voters have more opportunity,” Oliver said. “There would be fewer people on the extremes elected in each party.”

The absolute dysfunction in D.C. is largely due to this. Most districts are now heavily R or D, and candidates lean toward their base in primaries. And by base, I mean those who yell the loudest. Since many elected pols don’t have to worry about voters from the other party, they’ll act the fool trying to cater to the loudmouths.

Interestingly, Oliver owes her re-emergence in the Legislature to gerrymandering. Back in the early 2000s, the Dems, trying to hold off the surging GOP hordes, got inventive and created multimember districts that often pitted incumbent Republicans against each other. The scheme enabled Oliver to win a seat, and she has remained in office since.

Currently, almost two-thirds of the 236 state legislators are Republican, as are 10 of Georgia’s 14 members of the U.S. House. This is out of whack, because perhaps 53 percent of Georgians slant R. (Trump got 51 percent, and U.S. Sen. Johnny Isakson 55 percent, in 2016.)

I spoke with Ben Thorpe, an Atlanta lawyer litigating the North Carolina case, who spoke to the Georgia legislative committee this week. In North Carolina, 10 of the 13 U.S. House members are Republican. But in 2016, voters there narrowly elected a Democrat as governor. This leads one to believe the state is split evenly between R and D. So how’d they come up with 10 Republican congressional members? Computerized slicing and dicing of the partisan variety.

Thorpe said they hired a professorial computer whiz to run 3,000 simulations and create new maps for the 13 congressional districts in North Carolina. But, he said, the simulations did not use past voting records of residents going back almost a decade. Zero of the 3,000 maps came up with a 10-3 advantage, Thorpe said.

After the 2014 Georgia elections, I wrote a column noting that just 47 of the 236 legislative races in the general election had a Democrat facing a Republican. Many times, the candidates were running a fool's errand. The average victory of those 47 races was 67 percent. The closest race that year was in House District 105 in Gwinnett County, where Joyce Chandler, a retired teacher and Republican, won 52.78 percent of the vote.

It seems things are tightening up — but just a bit.

In 2016, there were 45 “active” races in the general election (two fewer than 2014) but the margin of victory had dropped from 67 percent to 65, which is still admittedly a butt-kicking.

But this time there were six races closer than Rep. Chandler's 2014 victory. In fact, she again had the closest race, winning 50.45 percent of the vote against Democrat Donna McLeod.

Of the six tight races, Republicans won four. Three incumbents were beaten, two of them Republicans.

The Dems are loading up for elections later this year, hoping to pick off a few Republicans in suburban seats. Still, those races are scarce and most voters statewide won’t really have a say in an election whose outcome is not pre-determined.

Perhaps one day those of us in the middle will get a real choice. Until then, it’s either arugula or kale.