Forensic genetic genealogy has helped close another Georgia cold case investigation, according to the DeKalb County District Attorney’s Office.

This time, the investigative technique that marries science with genealogy led to an arrest and indictment in a 1990 rape and double slaying.

Kenneth Perry, 55, was taken into custody earlier this month in his home county of Gwinnett, nearly 34 years after authorities said he brutally attacked two siblings he barely knew. A grand jury indicted him Tuesday.

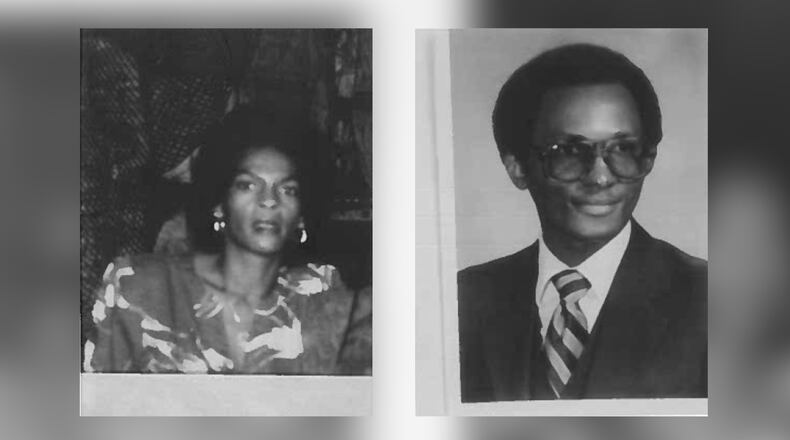

John Sumpter, 46, and his sister, Pamela Sumpter, 43, were both stabbed to death at their Redan apartment on July 15, 1990. Pamela Sumpter had also been raped. More than a quarter-century later, investigators used forensic genetic genealogy (FGG) to help confirm Perry was a match to DNA collected in a rape kit, prosecutors said.

“It’s been over 30 years since this terrible, evil tragedy happened to my brother and sister. We now have closure,” said James Sumpter, a sibling of the victims, at a news conference Wednesday morning.

It’s the latest case to use the groundbreaking technology, which has been instrumental in solving hundreds of cold cases across the country, including in Georgia. FGG taps into the vast web of genetic information housed in public genealogy databases and, combined with other investigative techniques, can help detectives identify once-anonymous suspects, victims and missing persons.

Credit: DeKalb County Sheriff's Office

Credit: DeKalb County Sheriff's Office

“Utilizing DNA and forensic genetic genealogy to identify suspects and victims of cold cases is inspiring new hope for families and cases that used to seem unsolvable,” DeKalb DA Sherry Boston said in a statement to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Authorities said it was pivotal to solving the Sumpters’ case, as John died at the scene; and while Pamela clung to life for a few weeks, she didn’t know Perry’s name, leaving detectives with very few clues.

Perry was an acquaintance who had recently moved to the Atlanta area from Michigan, Boston said at the news conference. The two men spent the day together before returning late at night to Sumpter’s apartment that he shared with his sister, officials said. Sumpter was likely showing Perry around his new city, DA spokeswoman Claire Chaffins told the AJC.

Pamela Sumpter was still awake when the men got back, according to prosecutors. She went to bed around 11:30 p.m., and that was the last time she saw her brother alive.

While the order of events is not known, Pamela Sumpter told detectives that she saw her brother lying on the apartment floor after she was attacked. She ran to a neighbor’s unit to call for help around 4:30 a.m.

Pamela Sumpter was then hospitalized for her stab wounds, and the rape kit was collected. She was also able to give police a detailed description of the attacker, Boston said, but she only knew the man by a nickname, Al or Eddie, the AJC reported at the time. She believed that he had either recently moved from Detroit or was visiting from there.

Pamela died three weeks later on Aug. 5, the DA’s office said.

At the time, the siblings’ family offered a $1,000 reward for information leading to an arrest, but nothing came of it.

For decades, the rape kit sat untested, as the Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS, was in its infancy as a pilot program in 1990. The national database wasn’t formalized until 1994 and didn’t become operational until 1998.

However, even today, the database is designed to return a match to a specific individual based only on evidence collected from convicted offenders, crime scene evidence or missing persons. So, it would only produce a match if the suspect’s DNA had already been uploaded.

At Wednesday’s news conference, Boston explained that Perry’s identity never surfaced in any DNA databases accessible to law enforcement.

In 2022, the GBI shipped off the evidence as part of its effort to work through a backlog of pre-1999 rape kits. Eventually, investigators found a match to an alleged rape in Michigan that was never prosecuted. That alleged victim had identified the suspect as Perry, and detectives later found a man with an identical name living in Loganville — just one county away from the Sumpters’ home.

But investigators needed to be sure the suspect and the Gwinnett resident were the same man. So when the DA’s office was awarded a federal grant for the use of forensic genetic genealogy to solve cold cases, the Sumpters’ slayings was one of the first cases to be submitted.

The process utilizes genealogical research, similar to how one might try to trace their ancestry, by reverse-engineering a family tree. Investigators can link the DNA sample from an unidentified person to any of that person’s family members who happen to be in the database. People who buy genealogy kits from services like 23andMe or Ancestry.com, which limit law enforcement access, can still elect to upload their DNA samples to databases that are accessible to police investigators.

In this case, the detectives’ goal was to confirm they were targeting the right guy.

The FGG analysis gave investigators enough evidence to secure arrest warrants for Perry, and he was booked into jail June 6. Once he’d been taken into custody, detectives executed a search warrant to get his DNA. Boston said Perry’s DNA matched the samples collected in both the Michigan and DeKalb cases.

“We are grateful that this federal grant is providing us the resources to reopen these cases using cutting-edge investigative techniques,” Boston said. “I am proud of my team for their tireless efforts to bring these decades-old cases to closure ... (and) I hope this arrest sends a message to anyone who has committed a violent crime in DeKalb County that we will not rest until we hold you accountable and get justice for victims.”

On Tuesday, Perry was indicted on two counts each of malice murder, felony murder, aggravated battery and possession of a knife during the commission of a felony. He also faces four counts of aggravated assault and one count of theft by taking.

About the Author