Two tropical storm systems near each other could wind up shielding the Carolinas from damage

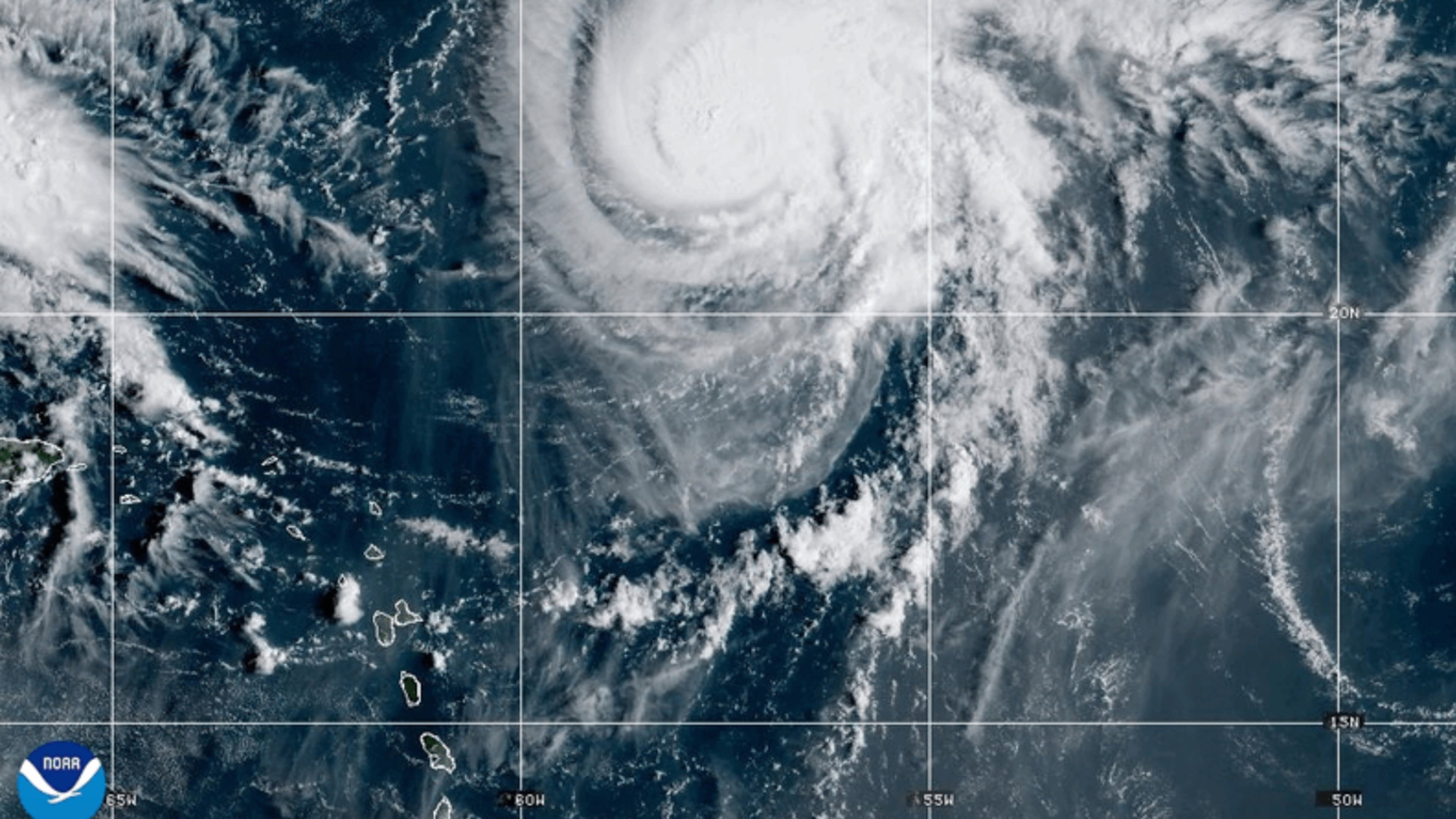

NEW YORK (AP) — As a wet tropical system chugged north toward the Bahamas on Saturday, its threat to the Carolina coast might be determined by its unusual interaction — maybe even a rare dance — with another tropical system that could steer the mess out to sea.

A still unnamed and developing tropical depression — likely to become Imelda — is heading toward the Carolinas and is expected to eventually become a hurricane with the potential to bring damaging heavy rains, especially if it stalls and keeps pouring for awhile.

The storm could hit early next week, so Carolina residents need to be aware, especially of rain and flooding possibilities. But slight changes in its path and speed will determine how much big, bad Humberto might come to the rescue.

The stronger, further east and older storm may get close enough to Imelda-to-be and start to interact. One possibility is that Humberto, which reached major hurricane status late Friday afternoon, could tug the smaller storm to the east. But if Humberto stays far enough away, it could allow Imelda to hover off the coast or make landfall.

“Even if we expect a slow down and an eastward turn, exactly when that starts and where it happens will make a big difference in how close the center gets to the coastline,” said National Hurricane Center Director Michael Brennan.

As Imelda heads past the coast of Florida, Brennan said there’s a tropical storm watch for parts of the state’s east coast. That means winds of at least 39 mph (63 kph).

“There’s going to be a high risk of rip currents. People are not going to want to be out in the water,” Brennan said.

As the storm proceeds further north, the Carolinas could face a significant flooding threat. The storm is already producing a lot of moisture — officials said it is expected to dump as much as a foot of rain on Cuba. If instead of turning out to sea, the storm makes landfall or stalls just off the coast, that’s when the potential for dangerous amounts of rain would come, according to University of Miami hurricane researcher Brian McNoldy.

As it moves, meteorologists are watching out for something incredibly rare that’s usually seen more in the Pacific: They could dance together, swirling around a spot in the middle. This was first seen more than 100 years ago and is called the Fujiwhara Effect for the Japanese scientist who discovered it. Two years ago, tropical storms Philippe and Rina did a little dance much farther away from the United States, McNoldy said.

Those were weaker storms with lower risks. That’s not the case here.

“This is more of a kind of high impact, high stakes forecast with potentially two hurricanes doing this right off the Southeast coast,” McNoldy said.

It’s something that typically happens when the storms are within 800 or 900 miles (about 1,300 or 1,500 kilometers) from each other.

“Not only would it be really neat to watch, but it would fling future Imelda out to sea," he said.

Most interactions will likely pull the younger, smaller system to the east and away from the coast, McNoldy said, adding that current models are showing that this possibility is growing more likely.

In a hurricane such as Humberto, the air rises up the middle and spreads out like a mushroom and then eventually sinks. It is that sinking air that may hamper Imelda-to-be, State University of New York at Albany atmospheric scientist Ryan Torn said.

This is so unusual that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is doing extra airplane missions to measure the atmospheric conditions between the two systems, Torn said.

This type of situation usually doesn't happen because there is sort of a natural spacing out between developing storm systems that chug west off Africa, Torn said.

___

Phillis reported from Washington.

___

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

More Stories

The Latest