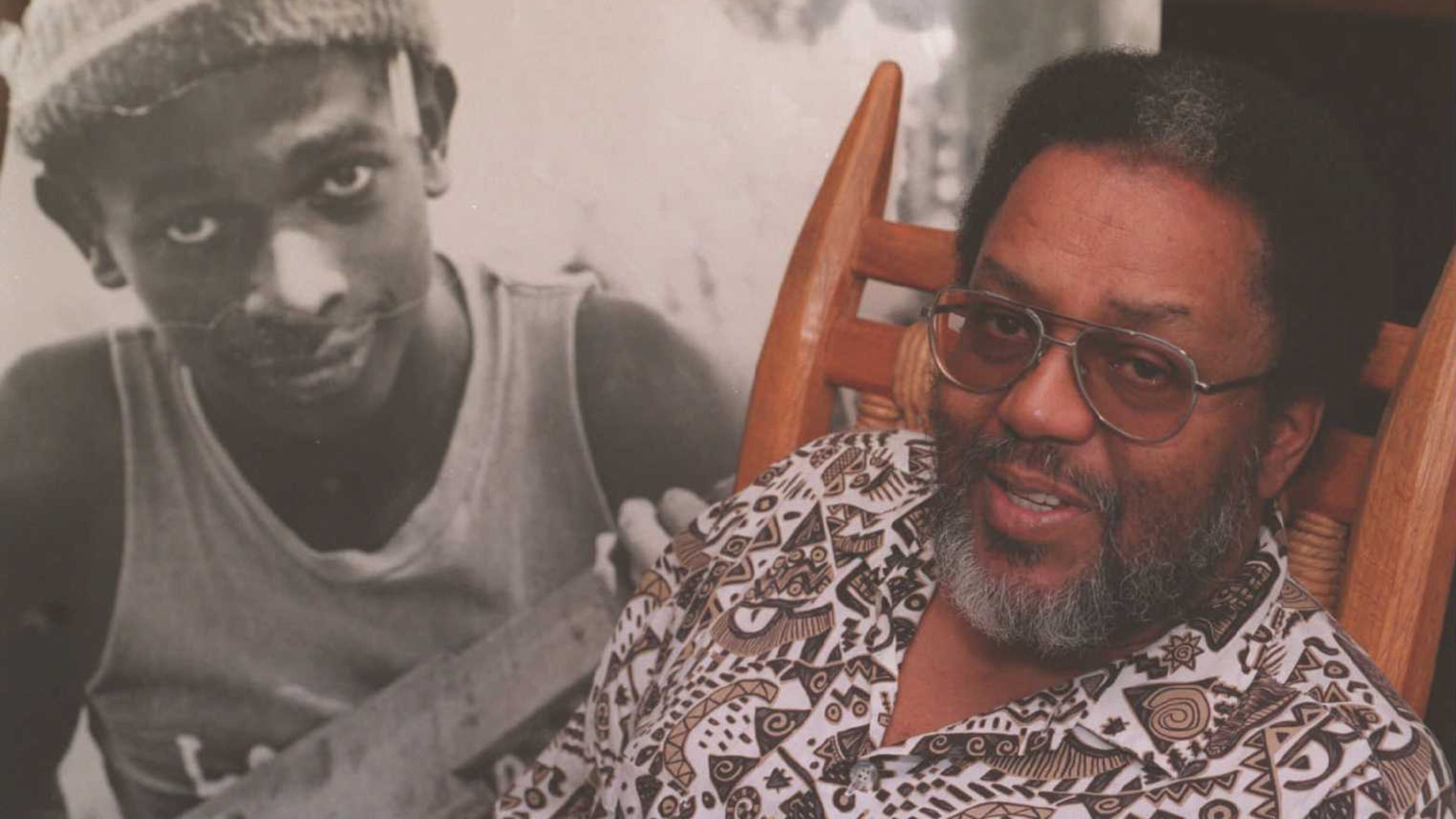

Worth Long made history, then recorded it

Whether he was with a Zydeco musician or a college professor, Worth Long treated everyone with compassionate curiosity and courtesy, making friends wherever he traveled.

He worked in the Civil Rights Movement, from Durham to Little Rock, Selma to Atlanta, and then became a folklorist who celebrated communities and their creators. He went on to stage festivals and collaborate on award-winning books, films and oral histories.

“Worth had been beaten and threatened, but he moved through the world with grace and ease,” says Aimee Schmidt, who worked as a stage manager during the 1996 Cultural Olympiad — which showcased Southern art and culture, where he was a presenter. “He was always engaged with everybody and wanted to know everybody’s story.”

A native of Durham, North Carolina, and later a sometimes Atlantan, Worth Westinghouse Long died in his daughter’s Marietta home on May 8 with his children Ramona and Will by his side. He was 89 and had been having heart issues for several years, his family said. He was the son of Gertrude Watson Long and the Rev. William Worth Long, an elder and “songbird” in the AME Zion Church who traveled in North Carolina when not tending his small farm outside Durham.

Two years as a medic in the U.S. Air Force during the Korean War took Long to Japan, where he saw traditional festivals and rituals and “became aware of folklore,” says Emilye Crosby, a civil rights historian at State University of New York-Genesco. Her parents were friends with Long, and she remembers being a child when he awakened the household by singing show tunes.

In the early 1960s, Long enrolled at Philander Smith College in Little Rock. There, he led sit-ins that helped desegregate the city’s lunch counters, and then he joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). His upbringing in the church — with his circuit-riding father — had prepared him. “People in these little churches loved his father, and he could get along with all of them,” Ramona says. “Worth used that ease when he traveled through different communities.”

Long became the SNCC project director in Selma in 1963, working with high school students and adults to stand up to white supremacy. He was arrested several times. The jailers tried to demean the people they arrested, and they beat Long after he insisted he was “Mr. Worth Long.” In getting to know people across the South, he encountered musicians and artists who enriched the local culture — and he realized their art was valuable and worth celebrating.

“Worth was both a gentle man and a gentleman,” says Courtland Cox, chair of the SNCC Legacy Project. “The culture was just part of him, and he saw the beauty in it.”

Later in 1963, Long organized a festival, bringing in folk singers Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger and blues musicians. In the early 1970s, Ralph Rinzler, director of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, suggested to Long to work with photographer and documentarian Roland Freeman to find Mississippi representatives for the 1974 Folklife Festival. Long had an encyclopedic knowledge of Southern blues singers and creators. Their collaboration led to the Mississippi Folklife Project, which was consolidated in the book “Folkroots: Images of Mississippi Black Folklife.”

“You could say he was an ethnomusicologist,” says Will Long. “He was interested in underappreciated music, like one-string guitarist Lonnie Pitchford.”

Richard Kurin, former director of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, said Long was under contract with the Smithsonian for different projects from the 1970s on.

According to Crosby, Long helped found the Mississippi Delta Blues Festival, worked on “Land Where the Blues Began” (with Alan Lomax), codirected “Mississippi Triangle” (a film about Chinese-white-African American relations in the Delta, with Christine Choy), conducted interviews for “Workers in the White House” with the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and the White House Historical Association. He worked with events such as the Southwest Louisiana Zydeco Festival, the 1982 World’s Fair in Knoxville, Tennessee, and the 1984 Louisiana World Exposition.

His radio history of the Civil Rights Movement in five Southern cities, “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?” won a Peabody Award. Along with Ralph Rinzler and Barry Lee Pearson, he received a Grammy nomination for “Roots of Rhythm and Blues: The Robert Johnson Era,” a recording with Columbia Records that grew out of a Smithsonian project of the same name. He received the Living Legends Award from the National Black Arts Festival and the Smithsonian’s Lifetime Achievement Award. In addition to “Roots of Rhythm and Blues,” Worth was also instrumental in the production of Fannie Lou Hamer’s “Songs My Mother Taught Me,” which was nominated for a Grammy in 2016.

In 2002, after Will Long’s mother died, Worth settled down “to take better care of himself,” says his son. “Although he was legally blind by that point, he showed up to watch my high school baseball games, and that meant a lot to me.” Father and son also worked together on an oral history project detailing Worth’s experiences in the Civil Rights Movement.

Historian professor Todd Moye worked with Long on interviews for the National Park Service’s Tuskegee Airmen project. “Worth was such a gifted oral historian because he connected on a deep level with people,” says Moye, at the University of North Texas.

Richard Kurin, now a distinguished scholar at the Smithsonian, remembers Long during the 1990 Festival of American Folklife. In one tent, Long was telling tourists, “We’re in a church in Mississippi, and tomorrow we’re going to march, we know we’re going to get beaten and arrested, and we’re afraid. So what do we do? We sing.”

The people in the tent began singing “This Little Light of Mine,” and then the group got up, left the tent and started marching on the Washington Mall as they sang.

“All these tourists, marching on the Mall! Worth gave people a sense of how you use songs to mobilize people,” says Kurin. “He was uncanny. He brought out the creativity and dignity of others.”

In addition to his children, Worth Long is survived by his daughter-in-law Jodi Harris Long, stepchildren Michael Mariolis and Maggie Mariolis (Joe Billesbach) and numerous nieces and nephews. A celebration of life will take place sometime in June. In October, the Oral History Association is planning a tribute to him.