Two centennials, one story: Delta and the Atlanta airport

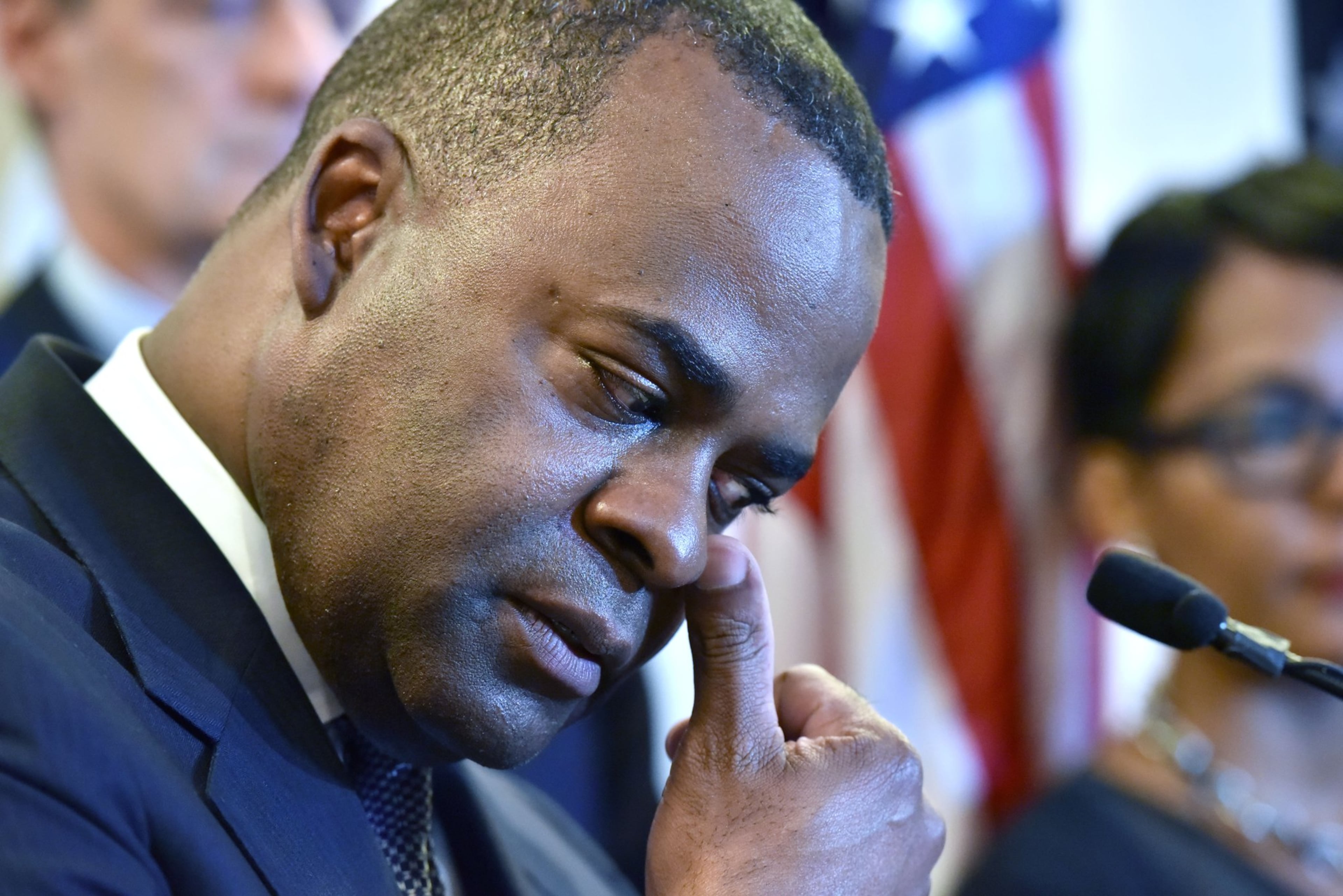

On a Wednesday in late April 2016, then-Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed and then-Delta Air Lines CEO Richard Anderson were fighting back tears.

It could have been a stuffy signing ceremony, locking Atlanta-based Delta into a 20-year lease with a 10-year extension.

But for the two leaders, the gravity of their signatures weighed heavily.

The contract guaranteed Delta’s headquarters would remain in the city it has called home since 1941 — and guaranteed Atlanta wouldn’t build another airport to threaten Delta’s preeminence.

The entities were making yet another long-term bet on each other.

Today, as both Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport and Delta celebrate their respective centennials, it’s impossible to tell the story of one without the other.

They are landlord and primary tenant. Construction partners. The city’s largest private employer. Some would say family members.

And both take credit for Atlanta’s growth into one of the country’s top metro areas, an international gateway home to 16 Fortune 500 companies.

“I had an awful lot to be emotional about,” Reed told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in a recent interview of the lease’s long-term ramifications.

The relationship, Reed said, is akin to a “sacred partnership,” and one of the “top three” relationships for any Atlanta mayor to prioritize.

“I don’t think people in Atlanta appreciate what the world looks like today if Delta’s headquarters are in Minnesota,” he said of an ultimately unfounded fear that Delta could have relocated to Northwest Airlines’ home base after the carriers’ merger in 2008.

Anderson told the AJC that Atlanta’s relationship with its hometown airline is different from any other he saw during his 25 years in aviation, including nearly a decade running Delta.

“No other city in the country makes the airport and the relationship with Delta a higher priority,” he said.

Delta and its subsidiaries’ passenger traffic, representing nearly 80% of Atlanta’s volume, is the reason Hartsfield-Jackson can claim the “world’s busiest airport” title.

“Many times, you can’t tell the difference … between who’s a manager for the airport versus a Delta leader at the airport,” Delta CEO Ed Bastian told the AJC Editorial Board this summer.

“And that’s the way we like it.”

And since the 1941 agreement that moved Delta’s headquarters from Louisiana to Georgia, when Atlanta chipped in $50,000 to help build the airline’s first hangar and office, the two have been as financially tied up as institutions can be.

While Delta was founded in 1925 in Macon, it’s more than fitting the airline and airport are celebrating their 100th birthdays in the same year.

Delta is “as much a part of Hartsfield-Jackson as anybody else,” Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens told the AJC.

“We’re celebrating 100 years tied together.”

Making Connections: 100 Years of Flight in Atlanta

A series of stories to mark the 100th anniversaries of both Delta Air Lines and Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport in 2025.

Delta turns 100: It all started with the boll weevil

The world’s busiest airport: A 100-year journey

How Atlanta claimed world’s busiest airport crown — and whether we can keep it

Delta’s next 100 years: ‘Our future is global’

Two centennials, one story: Delta and the Atlanta airport

100 years (mostly) union-free: Delta is still striving to stay ‘different’

Atlanta airport rings in 100 years with rare mayoral reunion, pep rally

You only turn 100 once. Here’s how Delta celebrated at lavish Atlanta gala

‘The factory’

Among Delta employees, the Atlanta airport has a nickname: “the factory.”

“It is a human factory,” Bastian told the AJC. “Over 100 million people that we move through that (airport). … It’s a city unto itself.”

And that’s been the key to the city’s aviation prowess, not the people traveling to and from Atlanta.

It’s the connecting passengers, and the speed and cost of moving them through.

Last year, 58% of passengers traveling through the world’s busiest airport were connecting, according to the airport.

As Bastian’s predecessor Anderson put it: “All you do in an airport hub is you manufacture. It’s a manufacturing facility, and it manufactures connections.”

One flight from Savannah to Atlanta can convert into airplane seats to any Delta destination in the world, he explained.

“If you go down to Savannah and check everybody’s ticket, people are going to Paris, Tokyo, London, Oklahoma City and Billings, Montana, but they’re all on the same airplane. So you get the economic power of indivisibilities,” Anderson said.

Airlines globally have been deploying this hub-and-spoke model for decades, but Delta and Atlanta have together taken it to its highest heights.

The vast majority of the roughly 108 million annual passengers passing through Atlanta every year are flying via Delta or its partners.

And from the Delta side, more than 40% of its global customers’ trips every day touch Atlanta, Bastian estimated.

That’s thanks to Atlanta’s famed modular concourse layout and efficient parallel runways.

But there’s also Atlanta’s all-important “cost per enplanement” or “CPE,” a crucial figure in any lease agreement: the cost to an airline per passenger boarded.

Among major U.S. hubs, only Charlotte has a lower CPE.

It’s important because Delta can choose where to connect its planes, Anderson noted.

It can choose to shift traffic to another hub if it’s cheaper to do so — and it has repeatedly threatened to do so to get its way over the years.

‘It’s all Delta’s money’

Although Atlanta’s identity and economic success is tied up in its airport, Anderson has a blunt take: Hartsfield-Jackson doesn’t have much without its hometown airline.

“This may not be popular,” he told the AJC. “It’s all Delta’s money.

“Go ask Cincinnati and Memphis, because I closed hubs in both places. Ask them if they think that all the money that came in the airport belonged to them,” he said.

“Well, if it did, why did you let it go away when we left?”

Cincinnati demolished an entire concourse after Delta pulled out of its once-thriving hub more than a decade ago, affecting thousands of jobs. Memphis lost several hundred jobs when the airline pulled back in 2013.

The financial ties are also why Delta doesn’t generally release control of its “factory.”

Most of the capital projects at the airport in recent decades, from the international terminal to the ongoing Concourse D expansion, are done with Delta’s money, oversight and sometimes its direct supervision.

“Delta has a lot of legal authority and power over the capital program here in Atlanta,” former airport general manager Ben DeCosta told the AJC. He oversaw, among much else, the construction of the fifth runway and international terminal.

“If Delta doesn’t agree, you can’t do it unless you’re spending your own money. If you want to have at least a penny of Delta’s money in a project, then they have to approve it.”

Indeed, at one point DeCosta and Anderson got into a disagreement over the soaring construction price tag of the international terminal in 2009.

Delta threatened to shift flights out of Atlanta if costs didn’t drop; DeCosta found a way to do so, the AJC reported at the time.

That being said, compromises go both ways.

Both have to agree on any major project, and some have fallen by the wayside as a result.

Sometimes in order to accelerate construction projects like Concourse E in the early 1990s, Delta has taken on management of the project itself, the airline’s longtime former real estate executive John Boatright told the AJC.

He took a hiatus from Delta to become an employee of the airport and manage construction projects including the fifth runway.

Delta and airport representatives are in constant communication during a project of that scale, he said. The stakes demand it.

If the project uses tax-exempt bonds under the city umbrella, as is common, the airline and airport need to be in lockstep, he said.

“Because the better the bond ratings are, then the better your (interest) rates are going to be when you price those bonds,” he said.

“So it’s inordinately important that you have all the people that will be signing that lease be hand in hand with the airport authority to make it happen.”

Hartsfield-Jackson‘s current general manager, Ricky Smith, told an Atlanta Press Club event this fall that any negotiations with an airline begin with “this notion that we both have shared objectives,” he said.

“Every time we find ourselves on the other side of the table on a tactical transaction, we can step back and remember that we all want the same thing.”

Risky business

Former Mayor Shirley Franklin, a veteran city executive, who is also a former Delta board member, noted this entwined relationship also reflects strategy on the part of Atlanta.

Back in 1980, then-Mayor Maynard Jackson chose to sign an unusually long 30-year lease, taking a bet on Delta and other airlines.

After Eastern Airlines liquidated in 1991, the city had another “strategic decision” to make, she recalled. It could have recruited many other airlines.

Instead, Delta was able to increase its Atlanta market share from 58% in 1988 to 88% in 1992, according to a federal report.

“It didn’t happen just because. It happened because there was a conscious decision to support the expansion of Delta,” Franklin said. “And Delta made a firm commitment to making this its primary home.”

“Some people consider that a bad deal,” she said. “It’s risky either way, it’s just a matter of balancing the risk.”

Bastian told the AJC that Delta’s influence has paid off across the metro economy.

He said he smiles when he sees announcement of a corporate relocation or factory opening: “None of them would have been possible if not for what we do.”

Gwinnett County has one of the largest Korean American communities in the country. “That’s because of the airport. That’s because of what Delta did here,” he argued.

Smith brushes off concerns that the airport is too reliant on its hometown airline, noting it’s a common dynamic at hub airports.

“I don’t think you’ll find another city that would see that as a problem. We certainly don’t see it as a problem. Delta is Atlanta. Atlanta is Delta.”

“Do we have to accommodate other carriers as well? Yes we do,” he said. “But the two aren’t mutually exclusive.”

However, it is undeniable that Delta’s influence has prevented other carriers’ efforts to make major headway in Atlanta.

Now-defunct AirTran Airways fought for 15 years to do so.

Southwest Airlines leadership said years ago they could not have entered Atlanta at a large scale without having acquired AirTran and its gates; they’ve since pulled back Atlanta operations dramatically.

The next-largest carrier at Hartsfield-Jackson, Frontier Airlines, had less than 7% of traffic in October.

Customers in cities with a very dominant carrier like Atlanta have a “love-hate relationship” with it, former airline executive and New York-based consultant Bob Mann told the AJC.

“It’s great you can fly to 400 places nonstop, any day. It’s also a crying shame you have to pay so much to do it.”

Frontier Airlines CEO Barry Biffle testified to the U.S. Senate this year that “fortress hubs” like Atlanta, with one dominant airline, can lock up gates, stifle competition and cause higher ticket prices.

We are family

Although Delta now sits atop its industry, it hasn’t always been that way.

The carrier fought through years of financial troubles culminating in filing for Chapter 11 protection in 2005, which left Atlanta’s leaders on edge.

Then-general manager DeCosta served on the airline’s unsecured creditors committee during the bankruptcy, which he said reflected the tight relationship.

One of his priorities was preventing Delta from being acquired by hungry airline suitors that might have threatened the headquarters.

“We just knew it was bad for Atlanta,” he said.

A decade later, in 2018, state politics caused a memorable kerfuffle.

Republican Georgia legislators tried to cancel the airline’s longstanding jet fuel tax break after it decided to end a discount for National Rifle Association members.

Democratic-controlled states and cities, including New York, Ohio, Virginia and Birmingham, urged the airline to move its headquarters.

Bastian smiled wryly at the memory in a recent interview: “We were being solicited hard.”

“But as I said then right in the heat of it, we’re not going anywhere. This is home. And you know, sometimes when you’re at home, you have little squabbles among family,” he said.

When asked if it would ever make financial sense for Delta to move its headquarters, Bastian paused to consider the question.

“No,” finally came the answer.

“You can’t replicate Atlanta. Atlanta is one of one in the world in terms of the aviation industry.”

And Delta has big plans to grow globally — and in its hometown.

“Whatever Delta’s future is in the decades to come, Atlanta will be pivotal to that.”

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has launched a series of stories to mark the 100th anniversaries of both Delta Air Lines and Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport.

This is the latest story in the series.