It has been 14 years since her father died, but Mallory Fannon still found herself choking up just a little on the main street of an upstate New York village when she started talking about herself, her dad, baseball and Chipper Jones.

Alan Luber had coped with the cancer by writing, and he sent hundreds of thoughts and messages to family and friends. Some included the joy in taking his “best friend,” as he called his daughter, to Braves games. Inning-by-inning they built their common love for a team and a game.

In one message – Fannon has compiled them in a self-published book, “The Cancer Chronicles: A story of Transformation and Triumph” – her father wrote:

“Last week, a couple of days before Mallory left for college, I took her to a Braves game. I was not feeling well, and it was very difficult for me, but I went and we managed to have a good time. This was very important to me – Mallory and I have gone to hundreds of games together, and I wanted to make sure we got to go to a game at least one last time.”

And if he paid more attention to the third baseman than other players, it was for one reason.

“(Jones) was one of his favorite players because he was one of my favorite players,” Fannon said.

How could she not make the trip from Johns Creek with her husband, Ken, to witness Jones’ induction into the Hall of Fame? She had a memory to serve.

“I wish my father would have been here with me – I know he would have definitely come if he were alive,” she said. “I know he is here with me in spirit.”

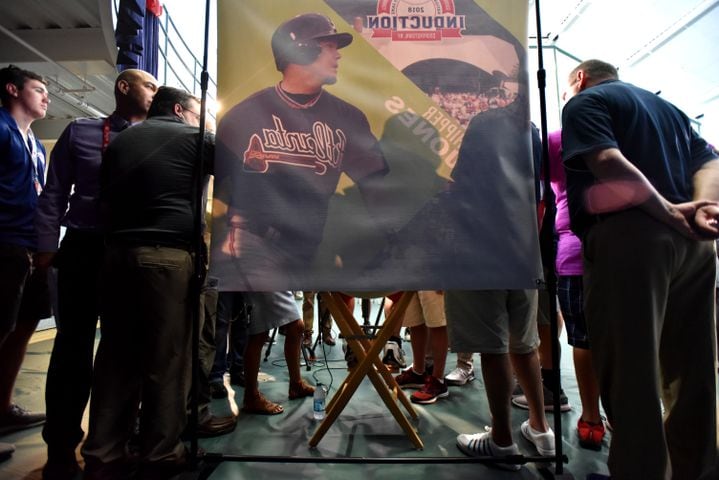

Credit: Hyosub Shin/AJC

Credit: Hyosub Shin/AJC

Before Jones takes the podium Sunday afternoon to tell the first-person story of his Hall of Fame career, there are others here who have something to say.

They stroll Cooperstown’s main street in the No. 10 jerseys and shirts, a place maybe they would never see if not for a charismatic Braves third-baseman. Disney be hanged – this is the happiest place on earth.

They hike out a day early to set up their chairs in the field where he’ll make his induction speech, surveying the best sightline to glimpse their guy.

On their baseball hajj to the Hall of Fame, they stop first to visit the Jones relics on display – his first and last major league home-run balls, the glove from his major league debut, his MVP award. Or touch the blank where his bronze plaque will go – he will spend posterity with Vladimir Guerrero on one side and Jim Thome on the other.

When Chipper Jones enters the Hall of Fame, he is taking an awful lot of people with him. He doesn’t have a story to tell without someone to celebrate it.

They range from Tim Jallen – a baseball groundskeeper in Fargo, N.D. with an authentic Chipper Jones goatee to match the jersey – to Alan Dorfman and his son, Joseph, from a more usual Braves address, Roswell. Dad bought his son’s Chipper Jones shirt. Son bought his dad’s Braves jersey with “Batboy” where a name should go.

Some are deep-in-the-weeds Jones fans, such as Carrollton’s Mike Morrison, whose own No. 10 jersey was customized with the word “Yicketty” across the back. That was Jones’ slang for a home run. “You have to be a real Chipper Jones fan to know what that is,” he said.

And there are those who came to the Jones camp more superficially. “He was the good-looking guy back then,” said Holly Herbrandson of Jacksonville, Fla.

Brent Edmondson was 8, and just coming of baseball age in Peachtree City when Jones broke in with the Braves. He, like a lot of other Georgia kids, fought to wear No. 10 in Little League. “I tried to swing like him. I tried to play like him. He was everything I wanted to be when I was a kid,” he said. It didn’t quite work out that way.

Edmondson is 30 now, and no closer to hitting major league pitching. But he’s still wearing No. 10.

All it takes is a moment to form the kind of relationship that would inspire a family to travel from Hayesville, N.C., to upstate New York to honor someone who wasn’t even family.

It was Jones’ last spring with the Braves, 2012, when Jeffrey Stewart and his family went south to watch the team train. A rainy day in Florida, hardly unusual. Jones could have just brushed by the few remaining fans in the stands to get to somewhere dry. But this day he stopped. He signed an autograph. Posed for a picture. And here they all are six years later.

What if Jones hadn’t stopped? Does Stewart suppose he would have made this trip with his wife and two kids? He shrugged doubtfully.

We’ll never know for sure, because Jones did stop and now they are all part of the same beautiful day.

About the Author