If you don’t get Bad Bunny now, learning Spanish before the Super Bowl won’t help

A friend of mine learning Spanish with Duolingo frequently shares her progress.

My favorite sentence she put together in the language learning app was: “Nunca confiábamos en nadie especialmente en el gato” … which means: “We never trusted anybody, especially the cat.”

It’s useful for understanding sentence structure but not so much for daily conversation.

And it will not be enough to understand Puerto Rican superstar Bad Bunny when he performs at the Super Bowl halftime show in 2026 — news that has grabbed headlines and invited controversy and character assassination.

The 31-year-old Spanish-language reggaeton and trap genre music artist who was born Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio created a sensation when he hosted Saturday Night Live Oct. 4 and addressed the audience in his native language to defend the dignity of American Latinos.

He followed those remarks with these 14 words in English: “And if you didn’t understand what I just said, you have four months to learn.”

These are provocative words from an artist who likes to push boundaries.

How Bad Bunny became a foil to Trump administration policies

Bad Bunny’s detractors call him a “demon Marxist” and “not American.” He was disavowed by the president of the United States in a recent interview. Kristi Noem, the Homeland Security secretary, crowed about how Immigration and Customs Enforcement would be “all over” the Super Bowl as part of its aggressive detention and deportation efforts.

Bad Bunny clearly struck a nerve.

Let’s be clear that because he was born in Puerto Rico, a U.S. commonwealth, Bad Bunny is an American citizen despite any effort to try to “other” him.

He also had a political awakening in recent years thanks in no small part to the first Trump administration’s response to Hurricane Maria battering Puerto Rico and the president throwing paper towels at desperate survivors in a relief center.

After comedian Tony Hinchcliffe called Puerto Rico “garbage” at a Trump rally just days prior to the November 2024 election, Bad Bunny endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris, Trump’s Democratic opponent.

The artist also recently said that he held his 2025 three-month residency in Puerto Rico — and away from the mainland United States — to keep ICE at bay.

So, he is likely on the Trump administration’s persona non grata list — even if the president denies knowing who he is.

But he’s not a nobody.

Bad Bunny was the most globally streamed Spotify artist in 2020, 2021 and 2022. Taylor Swift took the No. 1 spot the last two years, but he remained in the Top Five and continues to be the top streamed Latin musician.

He is so big that college professors, even at Emory University, are teaching classes about him as a cultural phenomenon.

Georgia’s Puerto Rican population includes prominent leaders

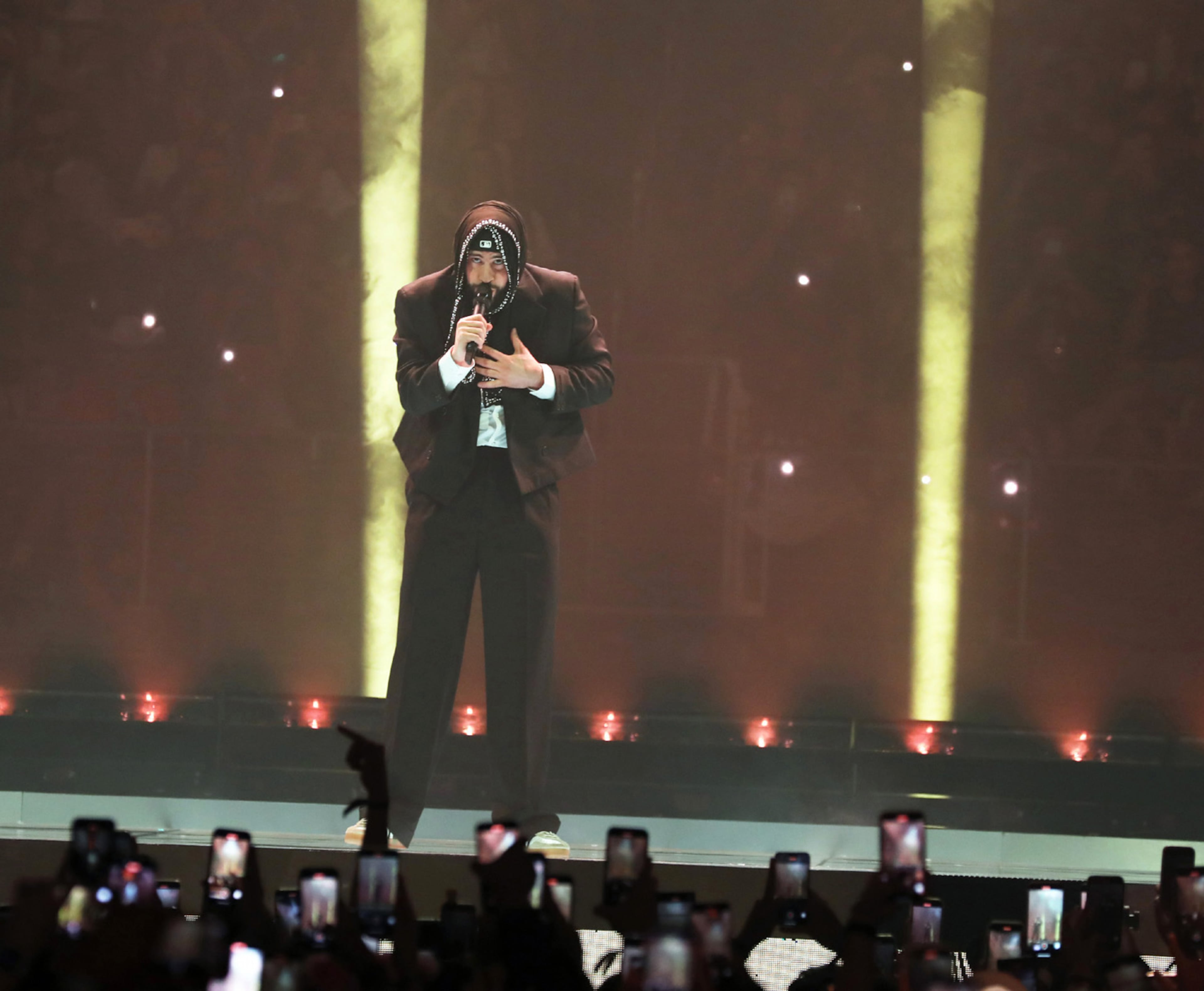

The last time Bad Bunny performed in Atlanta was in May 2024 for two days of concerts at State Farm Arena.

It was part of his sold out “Most Wanted” tour in 30-plus cities.

His performance reflected a growing embrace of Latin music in the Peach State where the Hispanic population exceeds 1 million and makes up 11% of residents.

The Hunter Centro at City University of New York (CUNY) estimated that 131,779 Puerto Ricans lived in Georgia in 2021. Among them are prominent leaders like Republican state Labor Commissioner Barbara Rivera Holmes, who was born in the capital of San Juan. On the Democratic side, former state Sen. Jason Esteves, a candidate for Georgia governor, is also Puerto Rican.

Of course, none of us are required to like Bad Bunny. Latinos are not a monolithic group. We don’t all like the same music.

I grew up with classical music and old-time Latin salsa stars such as Cuban artist Celia Cruz. So, it took me a while to warm up to Bad Bunny.

Although I speak Spanish, I couldn’t understand Bad Bunny the first time I heard his music because of his slang, colloquialisms and, well, unique sound. I’ll accept that maybe it was my age (is 49 old now?).

But his most recent album “Debí Tirar Más Fotos” (“I should have taken more photos”) captivated me.

It graduated beyond his previous hypersexualized and superficial lyrics into deep reflections on culture, roots and the effects of colonialism.

The album also became one of my regular running soundtracks because of its beat and musicality.

Little by little, his words became clearer and clearer to me.

It’s a message that might evade Super Bowl halftime show watchers at first. But it’s one worth going back to because of it’s a call to honor one’s history, roots and humanity.

David Plazas is the AJC’s opinion editor. Email him at david.plazas@ajc.com.