A federal judge could rule Wednesday on a far-reaching request to switch Georgia from electronic to paper ballots just eight weeks before November’s election.

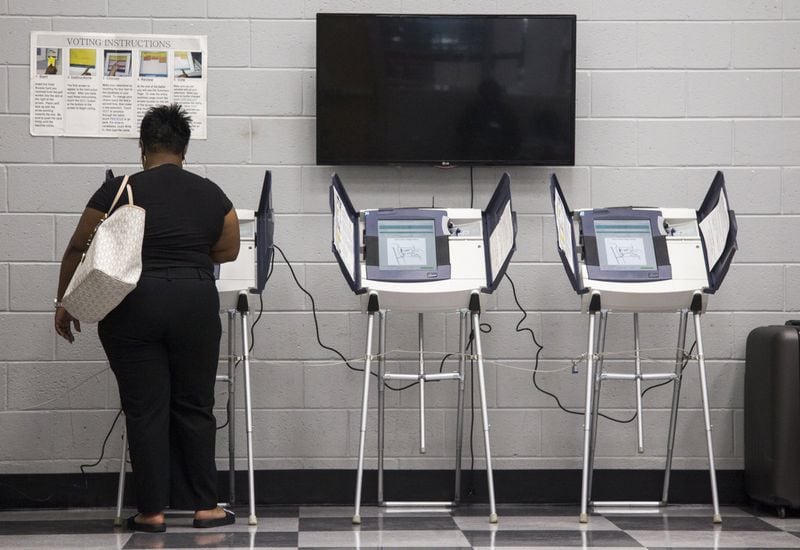

Changing the state's voting system on short notice would be a dramatic change, but concerned voters and election integrity groups say it would eliminate the possibility the state's touchscreen machines, which lack a verifiable paper backup, could be hacked.

They'll be in court Wednesday to ask U.S. District Judge Amy Totenberg for an injunction prohibiting election officials from using the state's 27,000 direct-recording electronic voting units, or DREs. Instead, voters would use pens to fill in paper ballots by hand.

Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp, the defendant in the case, strongly opposes a quick move away from the voting system in place since 2002. He said electronic voting machines are secure and that a rushed transition to paper would result in a less trustworthy election system.

But Donna Curling, the lead plaintiff in the lawsuit, said Georgia's electronic voting machines are inherently unsafe. If voting machines were penetrated by hackers, malicious code could rig elections, she said.

“There’s a lot wrong with the machines. They’ve been proven time and again to have security flaws that can’t be mitigated,” said Curling, a Roswell resident and member of a group called Georgians for Verified Voting. “This should have been done a long time ago.”

The judge will have to consider, among other things, fundamental voting rights and the feasibility of printing paper ballots for Georgia's 6.7 million registered voters.

Kemp, who supports a transition to paper ballots in time for the 2020 presidential election, said it would be irresponsible to force voters into an election crisis. He warned that early-voting locations would close in Fulton County because of staffing shortages, paper ballots couldn't be delivered in time in Cobb County and no county has budgeted for the expense statewide.

“The fact is that Georgia’s voting machines are aging, but they have never been compromised,” said Kemp, the Republican nominee for governor facing Democrat Stacey Abrams in November. “The other side is great at grabbing headlines, but in court, they have no evidence to substantiate their claims.”

Georgia is one of five states that rely entirely on DRE machines without a voter-verified paper backup.

While there’s no evidence that Georgia’s voting machines have been infiltrated, election security advocates say there’s no way to tell. If a hacker found a way into Georgia’s election system, they could switch results without leaving a trace.

The voting system will essentially be on trial during the Wednesday court hearing.

Plaintiffs intend to call several witnesses, including two professors with expertise in computer hacking, Georgia Election Director Chris Harvey and Fulton County Election Director Richard Barron. For the defense, State Election Board Chairwoman Rebecca Sullivan and former Georgia Secretary of State Cathy Cox. Kemp wasn’t on the list of potential witnesses identified in a court filing Friday.

An attorney for some of the plaintiffs, David Cross, acknowledged that changing to paper ballots wouldn’t be easy, but he said it’s essential.

“I don’t see how anybody can force Georgia voters to go forward with the current system, given that the vulnerabilities are unrefuted,” Cross said. “No one at the end of the day will ever be able to conclude that the election results in Georgia represent the will of voters under the current system.”

Harvey, the state’s election director, warned of “drastic consequences” if the state changes to paper ballots in such a short time.

Currently, less than 10 percent of voters use paper absentee ballots, and moving all voters to use paper would require millions of dollars, hastily crafted regulations, extensive voter education and revamped security measures, he said in a declaration filed in court last month.

It would also take more time to count paper ballots and report results, a process that’s currently finished in the early-morning hours after Election Day.

“Beginning a conversion to a new statewide system less than 90 days from Election Day presents a substantial risk of voter confusion, disruption, increased errors at polls, increased wait times, suppressed voter turnout and potential disenfranchisement,” according to Harvey’s declaration.

There’s no cost estimate for the expense of a rapid change to paper ballots, but Gwinnett County Elections Director Lynn Ledford estimated in court documents that it would cost roughly $1 per voter for a two-page ballot in her county.

Other states, such as Maryland and Virginia, have quickly replaced electronic voting machines with paper ballots, but not on such a broad scale or as quickly as the plaintiffs in the Georgia case are seeking.

In Maryland, the state was transitioning to paper ballots when election officials canceled the use of touchscreen machines for early voting before the April 2016 primary election. Maryland had already planned to use paper ballots on Election Day for the primary and general elections.

Maryland election officials changed to paper ballots early because voters said they were confused about a new touchscreen navigation of ballots, Maryland Deputy Election Administrator Nikki Charlson said.

“The meat of the changes had already been done. We were moving to paper ballots,” Charlson said. “That process took more than a year. Every single thing changes when you go from fully electronic to paper.”

In Virginia, its move to paper ballots began a decade before the state Board of Elections decertified touchscreen machines last year, a decision that required 23 cities and counties to acquire new voting equipment within weeks of the November election. That decision affected 140 Virginia precincts; there are 2,635 precincts in Georgia.

Still, it could be done in Georgia because each of the state’s 159 counties would be working at the same time to switch to paper, Cross said.

No matter the potential difficulties, one of the plaintiffs, Donna Price, said Georgia should do what it takes to make the change. She said Georgia’s voting machines can’t be trusted.

“A voting system like Georgia’s, with no paper record to audit, is like speaking your vote to a person behind a curtain and trusting that your vote is counted,” said Price, the director of Georgians for Verified Voting, who lives near Stone Mountain. “It’s best to trust but verify.”

The story so far

Then: Election integrity advocates filed a lawsuit last year seeking paper ballots in elections.

Now: A federal judge will consider a request Wednesday to prevent electronic voting machines in November’s elections.

What’s next: Georgia lawmakers plan to consider legislation next year to replace the state’s touchscreens with a voting system that includes a paper backup.

About the Author