Experts: DA should act to free man convicted in Ga. church murders

Brunswick District Attorney Jackie Johnson hasn’t said how she’ll respond to new evidence in a 1985 double murder case, but legal experts say she should immediately ask a judge to release the man convicted of the murders from prison.

Johnson’s office learned in late March that a DNA test linked a known former suspect to the scene where Harold and Thelma Swain were gunned down, according to court records. The husband and wife were killed by an unknown assailant in the vestibule of Rising Daughter Baptist Church in Camden County.

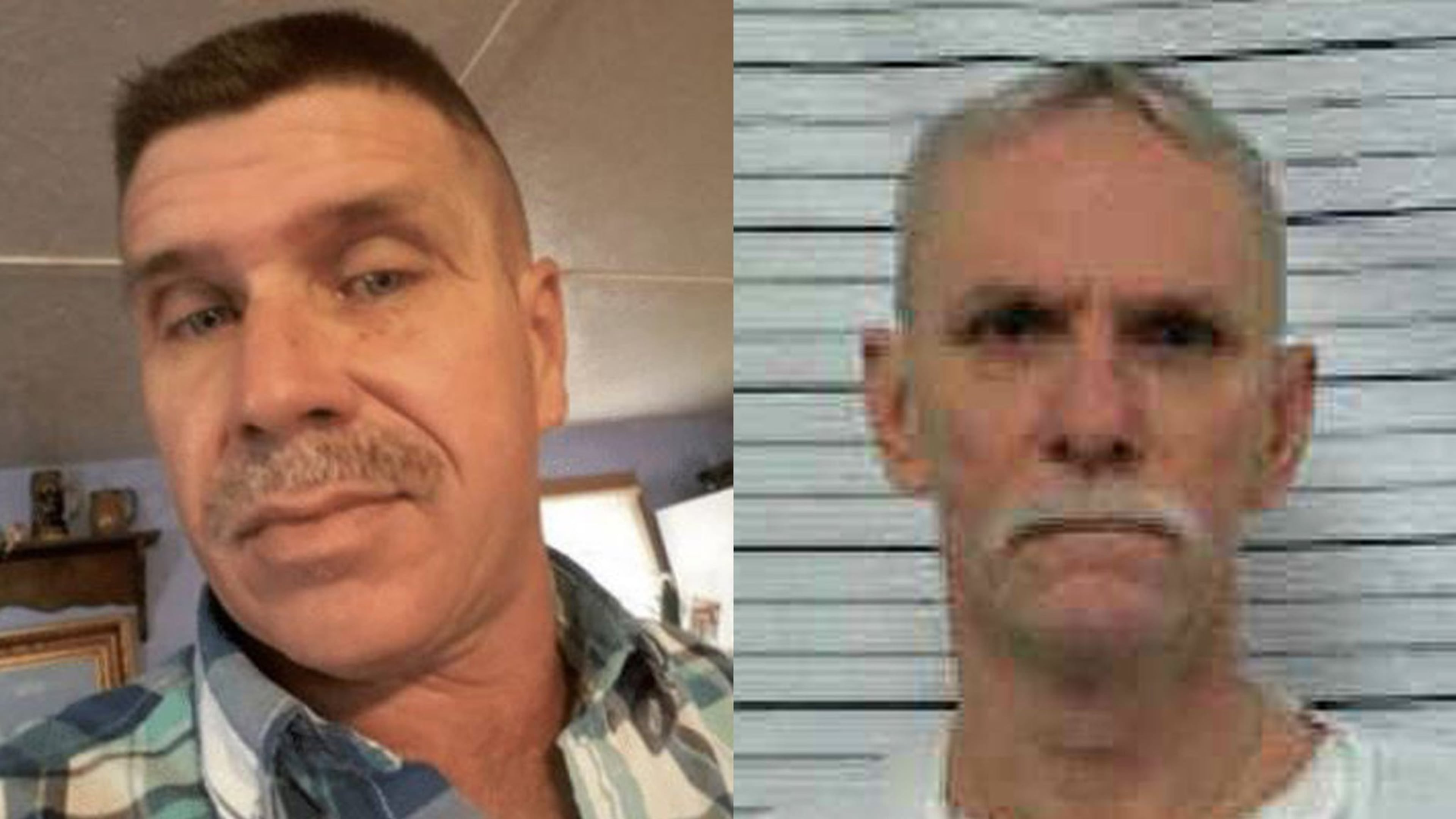

Erik Sparre was dropped as a suspect in 1986 because he had an alibi. Reporting by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution revealed problems with the alibi, leading attorneys for Dennis Perry, the man serving life for the murders, to conduct a DNA test. The test shows Sparre, who has said he is innocent, matches hairs that were stuck in the hinge of a pair of glasses found inches from the bodies. DNA from Perry, who has maintained his innocence, did not match the hairs in a test before his 2003 trial.

» SPECIAL PRESENTATION: "The Imperfect Alibi"

» FULL COVERAGE: The Rising Daughter investigation

Four legal experts — a retired prosecutor, a former judge, a professor and a civil rights advocate — reviewed the new findings and told the AJC that the DA’s office should move to free Perry from prison unless she has compelling evidence to refute the DNA findings. She should also launch an investigation into Sparre, the experts said.

“The right thing to do after him being locked up after 20 years is to release him,” said Georgia State University criminal law professor Russell Covey. “There seems to be powerful evidence pointing toward this alternate suspect.”

It isn’t clear if the district attorney’s office has taken any steps to investigate Sparre. In recent weeks the office has dealt with another high-profile shooting. Johnson recused herself after Ahmaud Arbery, 25, was shot to death on Feb. 23. One of the men involved once worked as investigator in her office. No charges have been filed in the Arbery case, which has gained national attention in recent days.

The office hasn't responded to requests for comment about the new evidence in Perry's case. DA Johnson told The Brunswick News last week she expects a recent motion for new trial by Perry to go before a judge sometime soon, but she still hadn't reviewed the case. The Camden County Sheriff's Office hasn't said if it is investigating. The GBI says it's still deciding what to do.

Sparre, 56, apparently learned for the first time about the DNA match not from investigators but from the AJC in a phone call last week. “I don’t have any glasses missing,” he said before telling a reporter to leave him alone and hanging up.

The test compared DNA taken from Sparre’s mother to DNA in the hairs found at the scene. The results show that the hairs in the glasses belonged to someone from Sparre’s maternal line, according to a motion for new trial filed by the Georgia Innocence Project and the King & Spalding law firm.

“The new DNA evidence is critically significant because it for the first time provides reliable forensic physical evidence linking a known suspect, Erik Sparre, to physical evidence at the crime scene,” the lawyers wrote.

Former DeKalb County District Attorney J. Tom Morgan said the DNA is enough to grant Perry a new trial, but other factors in the case also show Perry didn’t receive a fair trial in the first place. Morgan pointed to the $12,000 reward paid to Jane Beaver, the state’s star witness against Perry.

Beaver, who died in 2018, was the mother of Perry’s former girlfriend. Beaver testified Perry had told her he was going to kill Harold Swain because Swain had laughed in his face when Perry asked for money.

The jury didn’t know Beaver would receive money for her testimony, because the state didn’t tell the defense about the reward, according to Perry’s court filing.

Not disclosing the reward was a “violation and should result in a new trial,” said Morgan, who prosecuted scores of murders.

Another issue with the case against Perry is that the two initial lead detectives on the case investigated him long before Beaver came forward and decided it was virtually impossible for him to be guilty. Former Camden County Chief Deputy Butch Kennedy and retired GBI agent Joe Gregory say they investigated Perry in 1988 after a dubious tip. They learned he lived in Jonesboro at the time of the murders. Perry had worked until the late afternoon on the day of the murders, leaving him not enough time get to the church by 8:45 p.m.

The experts said there is, however, enough evidence to make Sparre a viable suspect.

Sparre became a suspect a year after the Swains were killed. According to a police report, his ex-wife’s family let an investigator hear a tape of a man they said was Sparre, who had been calling with threats: “I’m the motherf——- that killed the two n——— in that church,” the man said.

The ex-wife also said Sparre “hated blacks” and had a pair of beat-up glasses. An investigator showed her three pairs and asked if any looked like Sparre’s. She picked the pair from the crime scene.

The investigators dropped Sparre after Gregory, the GBI agent, spoke on the phone with someone claiming to be Sparre’s boss. The person said Sparre was on the clock at a Brunswick Winn-Dixie when the murders happened. But AJC reporting revealed that the true identity of the person who vouched for Sparre can’t be verified.

In a series of interviews with the AJC, Sparre has denied any involvement in the murders and has said he is not racist. He said he didn’t even know where the church was. He initially denied telling anyone he committed the murders, but finally suggested he was lying to scare his ex-wife.

It isn’t clear what became of the tape of Sparre’s alleged admission. It isn’t stored with the case file. All of the physical evidence in the case is also missing, though no one has been able to explain why.

Another person came forward in 1998 to say Sparre had suggested in a separate conversation that he killed the Swains. Now-retired deputy Dale Bundy, who declined to comment on the case, also disregarded Sparre as a suspect when he was investigating Perry. The initial investigators on the case didn’t test Sparre’s DNA in 1986 because such testing was in its infancy.

The experts said the fact that the tape of Sparre has gone missing doesn’t mean those who heard the tape can’t testify about what Sparre said. (Sparre’s ex-wife is dead. Her brother, Emmett Head, is listed in police records as the person who was on the phone when Sparre allegedly made the statement. Head declined to comment.)

“This is a pretty compelling picture (against Sparre),” said Lester Tate, former head of Georgia’s Judicial Qualifications Commission. “I think he certainly needs to be investigated.”

After reading Perry’s motion for new trial, Stephen Bright, the former director of the Southern Center for Human Rights, gave a succinct opinion: “Perry should be released immediately. Sparre should be investigated.”