Why freezing rain has millions at risk of losing power — and heat

ATLANTA (AP) — Every morning this week, Newberry Electric Cooperative CEO Keith Avery walks into his office and turns on The Weather Channel. Then he starts making calls, lining up crews and equipment to respond to outages if a forecasted ice storm cripples power across South Carolina.

Avery has dealt with disasters before. Nearly every one of his 14,000 customers lost power when the remnants of Hurricane Helene tore through in 2024.

But the approaching ice storm has him even more worried because ice-coated trees and power lines can keep falling long after the storm itself has passed.

“I hate ice storms,” Avery said. “They are worse than hurricanes.”

Officials across the eastern two-thirds of the U.S. have been sounding the alarm about the potential for freezing rain to wreak havoc on power systems. In the South, especially, losing electricity doesn’t just mean the lights going out. It means losing heat.

That's because a majority of homes are heated by electricity in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

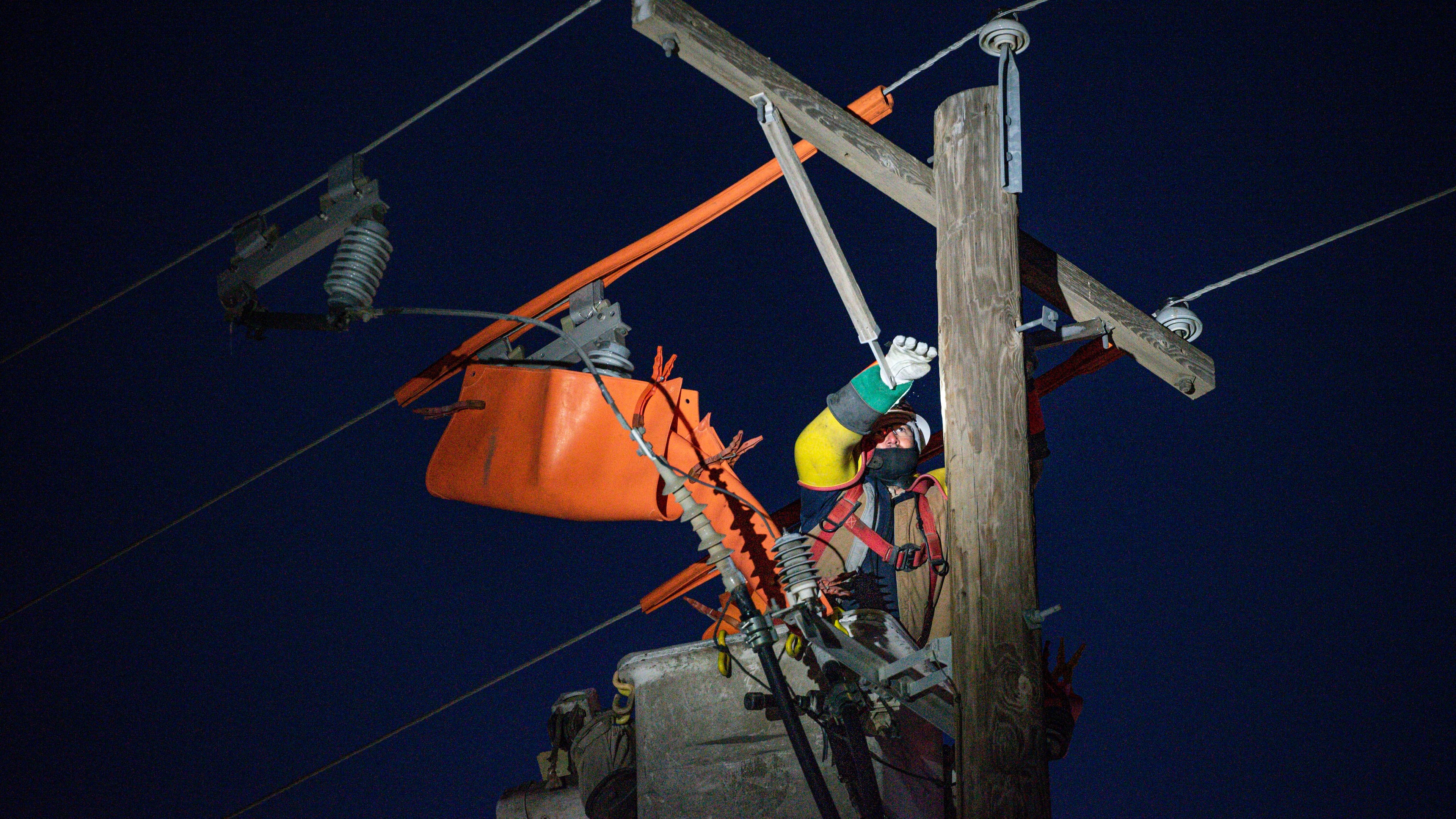

Ice storms, Avery said, are especially punishing because of what happens after they move out: Crews struggle to reach damaged lines on ice-covered roads; cold, wet weather takes a toll on workers; and problems can linger for days as ice-laden branches continue to snap.

“You get a power line back up and energized, and just as you leave, you hear a loud crack and boom, there’s a tree limb crashing through what you just repaired,” Avery said.

Lessons from Winter Storm Uri

Texas experienced the worst-case scenario in 2021, when Winter Storm Uri's freezing temperatures crippled the state's power grid for five days and led to 246 storm-related deaths, according to the Texas Department of Health Services.

But experts say Uri’s damage stemmed largely from poorly weatherized power plants and natural gas systems, not downed power lines.

“The main lesson was to enforce requirements for utilities to be ready for cold weather,” said Georg Rute, CEO of Gridraven, a Texas-based firm that analyzes power system risks for grid operators.

Rute said utilities have applied lessons from Uri, and while he does not expect a repeat of that kind of grid collapse, he warned that other vulnerabilities remain, including transmission lines tripping during extreme cold.

Gov. Greg Abbott on Thursday gave assurances to Texans about the state’s power grid. The Electric Reliability Council of Texas has said grid conditions are expected to be normal during this weekend’s storm.

“The ERCOT grid has never been stronger, never been more prepared, and is fully capable of handling this winter storm,” Abbott said.

The governor added, though, that residents could lose power as ice weighs down power lines and trees fall onto them. But, he said, energy providers are prepositioned to fix any outages, and there’s been an effort to clear trees and branches near power lines in recent years.

Outages hit hardest in vulnerable communities

Winter Storm Uri also exposed disparities in how outages affected communities, said Jennifer Laird, a sociology professor at the City University of New York’s Lehman College who studies energy insecurity. Researchers have found that residents in predominantly Hispanic areas experienced more outages, while Black residents were more likely to face outages lasting a day or more.

Laird said outages expose vulnerabilities people don’t anticipate, from medical equipment that requires electricity to families with infants who rely on refrigeration for breast milk. Younger households and those with lower levels of education, in particular, are less likely to have contingency plans in place, she said.

"There are lots of ways that we’re dependent on energy that we don’t realize until a crisis hits — and then it really exposes those vulnerabilities,” Laird said.

Even if this weekend’s storm does not produce significant outages, the financial burden on families could linger for months. About 1 in 6 U.S. households are already behind on their energy bills, and with millions expected to turn up their heaters during the cold snap, that number could rise, Laird said.

“A month or two after the storm hits, suddenly the bill hits,” she said. “We could see a rise in disconnection notices and disconnections.”

Utilities prepare for the worst

Utilities in the Southeast have also warned customers to prepare for possible outages. Duke Energy, which serves more than 4.6 million customers in North and South Carolina, urged residents to be ready for multiple days without power. The utility said more than 18,000 workers would be ready to respond once conditions are safe.

The Tennessee Valley Authority, which serves more than 10 million people across seven states, said it has invested hundreds of millions of dollars in weatherization since a 2022 winter storm and has built-in redundancies to reroute power if a line goes down.

“It takes a lot of snow and ice to down one of those big lines,” TVA spokesperson Scott Brooks said.

___

Collins reported from Columbia, South Carolina. Associated Press writers Travis Loller in Nashville, Tennessee; Gary Robertson in Raleigh, North Carolina; and Jamie Stengle in Dallas contributed to this report.