Kemp signs Georgia ‘police protections’ measure into law

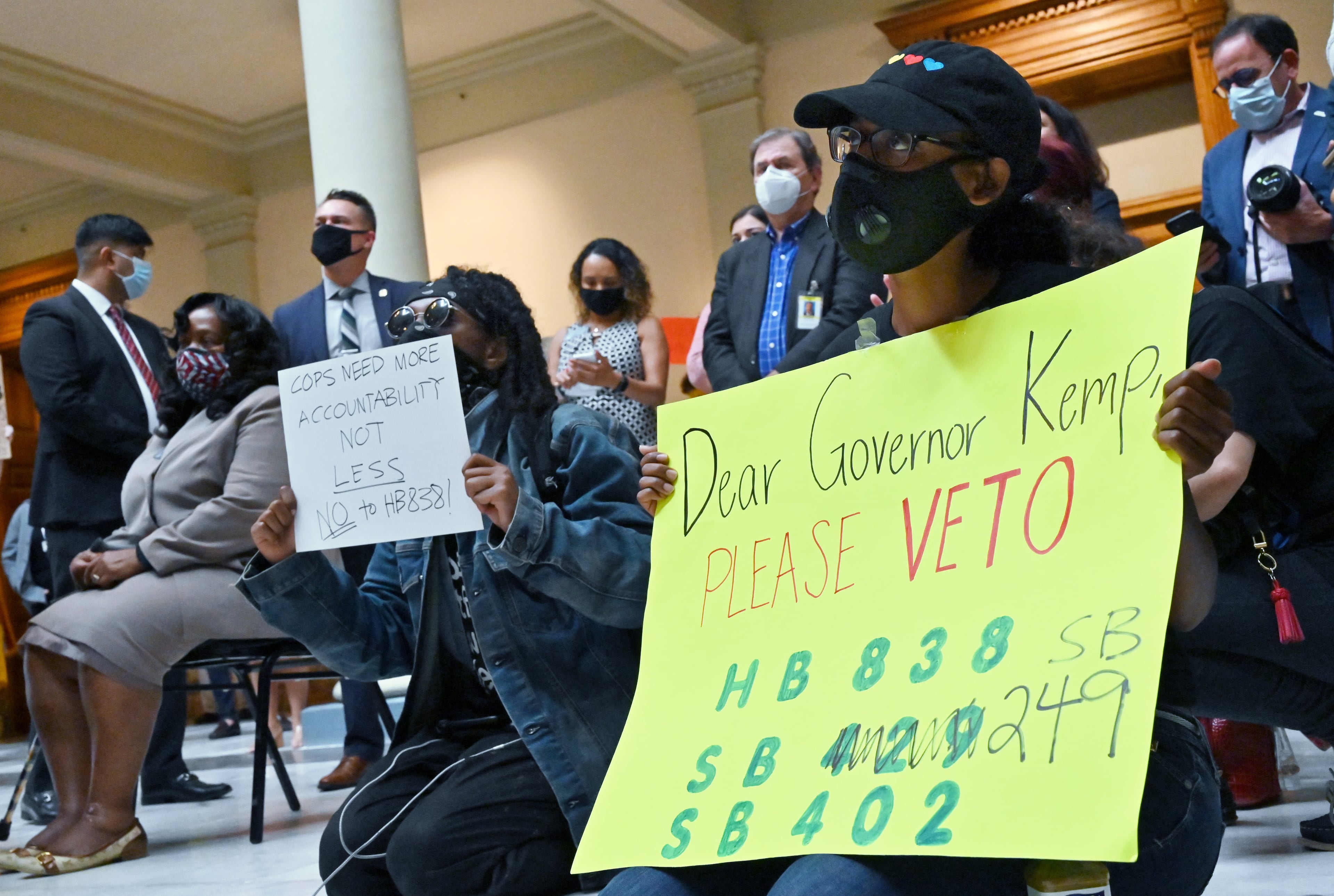

Gov. Brian Kemp signed a proposal into law Wednesday that Republicans pushed to grant police new protections despite stiff opposition from critics who said it creates a messy tangle of legal problems.

The measure, House Bill 838, was the most significant proposal left on Kemp’s desk at the close of a 40-day period to sign or nullify bills, though he also approved a measure that would curtail the ability of people to sue businesses and health care providers if they are diagnosed with COVID-19.

In a statement, Kemp said he took action because he has attended the funerals of too many law enforcement officers killed in the line of duty, and he called the measure a “step forward as we work to protect those who are risking their lives to protect us.”

“While some vilify, target and attack our men and women in uniform for personal or political gain, this legislation is a clear reminder that Georgia is a state that unapologetically backs the blue,” Kemp said.

It was shoehorned into and then carved out of a landmark hate-crimes measure that won overwhelming approval after years of inaction in the Georgia Legislature, gaining traction only after graphic video emerged of the shooting death of Ahmaud Arbery, a Black man killed in Glynn County in what prosecutors say was a racist attack.

As part of a compromise to win approval of the hate-crimes bill, Senate Republicans demanded the passage of a separate proposal that would create the new offense of “bias motivated intimidation” of a police officer or other first responder.

State Sen. Harold Jones, an Augusta Democrat who worked on the hate-crimes legislation in the Senate, was among the lawmakers who had urged Kemp to veto HB 838.

“That’s what happens when you rush through legislation when it doesn’t have good intent,” he said. “There could have been a better way to increase police protections, if they were needed and I’m not saying they were, in the next legislative session instead of rushing this through.”

While the hate-crimes legislation earned widespread support, the more polarizing companion piece passed on a party-line margin in the Senate — and eked by with one vote to spare in the House — over the objections of critics who saw it as unnecessary and tone deaf amid protests over police brutality. Many pointed to a 2017 law that added penalties for people who assault police officers.

Its supporters called it a crucial endorsement for law enforcement officials at a tumultuous moment.

“It’s disappointing that supporting law enforcement has become a partisan issue,” House Speaker David Ralston said. “We value and stand with the men and women who wear the badge in Georgia, and House Bill 838 demonstrates that unequivocally.”

‘Deeply disappointed'

At first glance, Kemp would seem assured to support HB 838. He’s taken the side of law enforcement officials during demonstrations over police brutality, deployed the National Guard after the Georgia State Patrol’s headquarters was vandalized and released a video message in support of police immediately following sickout protests by Atlanta officers.

But civil rights groups and legislators raised concerns that the hastily written legislation could weaken protections for police officers in some cases and have other unintended consequences.

For one, the American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia has said the measure could reduce potential prison sentences for the murder of a police officer from mandatory life in prison to a maximum of five years behind bars because of a conflict in the law.

Other critics fear that it could give police officers new powers to chase down street protesters in the state’s civil courts by granting them broad authority to sue people, groups or corporations that infringe on their civil rights.

“We are deeply disappointed that the governor would allow legislation of this sort to go into law,” said Andrea Young, the ACLU of Georgia’s executive director, who said state law already includes “sufficient protections” for law enforcement officers.

“HB 838 was hastily drafted as a direct swipe at Georgians participating in the Black Lives Matter protests who were asserting their constitutional rights,” she said.

Other measures

Kemp, a first-term Republican, wasn’t shy about using the red pen last year when he vetoed 14 measures, including one that would have required elementary schools to schedule recess each day and another that would have mandated that school systems update safety plans and conduct drills.

He echoed a tone set by his predecessor, Gov. Nathan Deal, who was not afraid to send measures to the scrap heap. Deal vetoed both a "religious liberty" measure and a campus gun proposal in 2016, and in 2018 he nullified 21 bills — the most of his eight-year tenure.

Kemp’s four vetoes this year involved measures that attracted little controversy. Among them was a proposal for a nonbinding referendum on whether to abolish the Glynn County Police Department that he nixed after he approved a separate measure for a binding vote.

He’s already signed the other highest-profile measures that lawmakers adopted this session, including laws to extend the time some new mothers can receive Medicaid benefits, cut down on “surprise” medical bills and allow stores to deliver beer, wine and liquor to Georgians’ homes.