Officer John Calhoun was on duty in the isolation-segregation unit at Smith State Prison in South Georgia late on a Sunday night when he witnessed a disturbing sight.

Inside Cell J1-124, Richard Tavera, a 24-year-old inmate with a history of mental problems, was looping one end of a bedsheet around a sprinkler on the ceiling and the other end around his neck.

Calhoun immediately recognized that he was dealing with a life-or-death situation, but he chose not to enter the cell. Instead, following regulations, he called for help.

Then he watched and waited as Tavera hanged himself.

The circumstances surrounding Tavera’s death on that December night in 2014 are now the basis of federal lawsuits that paint a startling picture: Georgia prison guards refusing to go into the cell of a troubled inmate even as they saw him in the act of committing suicide.

"How could they not have the heart to save someone they see trying to harm himself?" asked Tavera's mother, Maria Arenas, whose suits in Georgia and Texas accuse the Georgia Department of Corrections and the prison employees involved with violating her son's civil rights.

Essentially mirroring the Glennville prison's own incident report, the lawsuits describe how Calhoun saw Tavera placing the makeshift noose around his neck but didn't enter the cell until a lieutenant arrived 10 minutes later. According to the lawsuits, another officer, a sergeant, answered Calhoun's call within eight minutes but also declined to enter the cell until the lieutenant showed up.

Tavera, a native of Austin, Texas, who had been placed in isolation-segregation a day earlier for behaving erratically in the prison infirmary, was pronounced dead by the Tattnall County coroner even before he could be transported to the local hospital by paramedics.

The GDC declined to respond to questions from The Atlanta Journal-Constitution regarding the incident, but the state’s lawyers wrote in court filings that the officers did nothing wrong and were only following protocol designed to protect prison staff from inmates who fake illness for nefarious purposes.

The department’s standard operating procedures for officers working in isolation-segregation require at least two be present any time a cell door is opened. That’s because those units, also known as lockdown, house some of a facility’s most disruptive offenders.

The policy is the industry norm, according to a variety of correctional experts contacted by the AJC. However, emergencies demand that the second officer be on the scene as quickly as possible, preferably within four minutes, the experts said.

"For the officer's safety, maybe he doesn't open the door right away," said Raul Banasco, who has overseen jails and prisons in Florida and Texas for more than 30 years. "But someone should have been there within one or two minutes. We're talking crucial seconds."

The lawsuits suggest that the prison’s warden at the time, Stanley Williams, maintained a separate policy prohibiting officers from entering cells unless they had permission from a lieutenant or higher ranking officer.

The AJC could find no written policy requiring such approval.

Williams, who last August was named warden at Valdosta State Prison, did not respond to messages from the AJC.

GDC declined to provide the AJC with video or any investigative files stemming from the incident. In refusing to make the material available, the department cited a state statute that says “investigative reports and intelligence data” compiled by prison investigative units are “state secrets and privileged under law.”

A persistent problem

Hundreds of inmates and detainees commit suicide every year in U.S. correctional facilities. The problem is particularly acute in local jails, where staffing and resources are limited, but state prisons aren’t immune.

Between 2001 and 2013, suicides accounted for 6 percent of the inmate deaths in U.S. state prisons and 4 percent of those in Georgia, according to data compiled by the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

In most instances, inmate suicides are discovered after the fact, leading investigators to focus largely on whether officers were paying proper attention.

That was how events unfolded in the highly-publicized case of Sandra Bland, the Chicago woman who used a garbage can liner to hang herself in a Texas jail after a controversial traffic stop two years ago. Bland’s mother received a $1.8 million settlement after guards admitted they had falsified jail monitoring logs.

The notion that the guards looking in on Tavera took no action even when they saw him fashioning the bedsheet noose is stunning, inviting an even greater level of criticism, some experts told the AJC.

"That's the most tragic example of people following some bureaucratic rules at the expense of common sense and human life," said Stephen Bright, the law professor who helped found the Southern Center for Human Rights. "That's just the most egregious thing I think I've heard in terms of lack of accountability and lack of common sense and (concern for) human life."

Robbery in Roswell

Tavera entered the Georgia prison system in January 2013 after he was convicted along with three other men of robbing three employees of a Roswell Publix as the employees were leaving the store.

Tavera and the other men, all of whom had come to Atlanta from Austin to work temporarily in construction, pleaded guilty to aggravated assault and robbery by intimation after they were charged with using an “offensive weapon” — a beer bottle — to take cash and cell phones. Tavera received a sentence that included three years in prison and essentially banishment from the state. He received a tougher sentence than others involved in the robbery because of a previous federal conviction in Texas for conspiracy to distribute cocaine.

The mental health evaluation for Tavera when he entered prison noted that he was hospitalized for a week when he was 16 after he overdosed on pills. The overdose was an effort to get attention after his parents divorced, the evaluation said.

Tavera also had previously been prescribed the antidepressants Zoloft and Trazodone for bipolar disorder, according to the evaluation.

Arenas described her son, the third of her four children, as a normal young man who liked to cook, repair household items and draw. But he also was prone to mood swings, particularly after she and her husband separated, she said.

“Sometimes he would be happy and sometimes he would be angry for no apparent reason,” she said.

Unusual behavior

Credit: Georgia Department of Corrections

Credit: Georgia Department of Corrections

Tavera had hoped to be released from prison in November 2014, but he was informed in July that he would be required to serve his full sentence. The letter he received from the State Board of Pardons and Paroles cited his “institutional conduct” and gave no details.

Arenas said her son told her he was moved to Smith State Prison, a closed custody facility that houses more dangerous offenders, after he was caught with a cellphone at another facility and Tasered by the guard who found him with it.

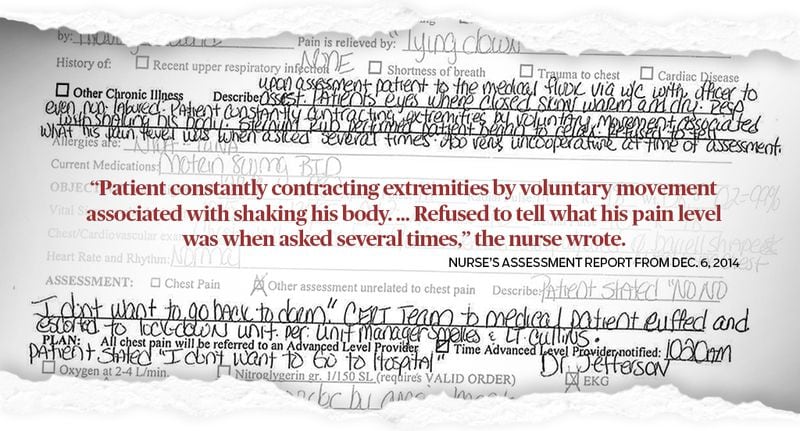

On Dec. 6, 2014, Tavera was in the infirmary complaining of chest pains when he began to behave in an unusual manner, according to a report prepared by the nurse on duty.

"Patient constantly contracting extremities by voluntary movement associated with shaking his body. … Refused to tell what his pain level was when asked several times," the nurse wrote.

According to the nurse, Tavera also said, “No, no, I don’t want to go back to the dorm.”

The correctional emergency response team was contacted, and Tavera was handcuffed and escorted to lockdown.

`I instructed him to stop’

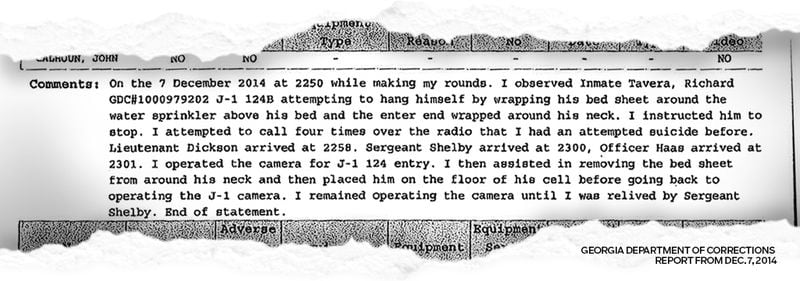

The next night, Calhoun was making his rounds when he saw Tavera attempting to hang himself. In the incident report, the guard put the time at 10:50.

“I instructed him to stop,” Calhoun said in the report. “I attempted to call four times over the radio that I had an attempted suicide.”

In the report, Sgt. Mark Shelby said he went to the cell after hearing Calhoun’s call for help, listing the time of his arrival as “approximately” 11. Looking through the cell window, he saw Tavera with the sheet around his neck and hanging from the sprinkler, he said.

“I shouted several times ‘Hay, hay’ (sic) to get the inmate to respond, but he didn’t,” the report quotes Shelby as saying.

Shelby said Lt. Marvin Dickson then arrived at the cell and ordered Calhoun to open the door. When they got inside the cell, Shelby said he and Dickson removed Tavera from the noose and laid him on the floor.

“I then began giving CPR to the inmate,” Shelby said. “Once available, I also deployed the defibrillator device and gave rescue breaths until EMS arrived.”

Shelby’s timeline differs slightly from the one provided by Calhoun, who said Dickson arrived at 10:58, two minutes ahead of Shelby.

Shelby told the AJC he was “two buildings over” when he heard Calhoun’s call. “By the time I got there, it was over,” he said. He declined to answer further questions because of the lawsuits.

Calhoun, who resigned his position at the prison in January 2016 and now works as a guard in the Texas prison system, declined to discuss the incident, citing the ongoing litigation.

Before becoming a correctional officer, Calhoun served in the Navy, where his duty included guarding terrorism suspects at the controversial Guantanamo Bay detention camp, according to his GDC personnel file.

Dickson, in his account, acknowledged that he was notified of the attempted suicide at 10:50. He said he retrieved two video cameras and pepper spray before going to Tavera’s cell. He did not list the time he arrived.

Efforts by the AJC to contact Dickson were unsuccessful.

None of the officers were disciplined as a result of the incident, GDC personnel records show. Dickson was demoted in rank to sergeant in March 2015, but that was because he falsified a document to make it appear he had transported an inmate when in fact he hadn’t done so, the records state.

A search for answers

Arenas, who speaks mostly Spanish and was interviewed through an interpreter, said she was initially told only that her son had committed suicide. She said she repeatedly called prison officials seeking details and was told the case was still “open” and nothing more could be said about it.

A month after the suicide, she said, she drove from Austin to Georgia with her daughter and her daughter’s husband hoping to visit the prison. About an hour outside of Glennville, they called the prison to say they were on the way and were told not to bother; they wouldn’t be allowed into the facility, she said.

“It just seemed like they weren’t interested in helping me,” she said.

Finally, with the aid of an English-speaking friend at the flooring and carpet store where she works, Arenas obtained her son's medical records and the incident report.

Those documents now form the backbone of her lawsuits. She is suing the GDC, Williams, Dickson and Shelby in Georgia and Calhoun in Texas.

Filed late last year by two Austin attorneys well known for successfully taking on the prison system in Texas, Jeff Edwards and Scott Medlock, the suits seek unspecified damages.

"No reasonable correctional officers would have chosen to stand by and let a man die while it was obvious he was attempting to take his own life," the suits state.

Arenas said her main objective is to get all the facts about her son’s death. She wants to know the truth, she said, “so I might find some sense of peace.”