- Pregnant woman begging with young boy photographed riding off in Mercedes-Benz

- Must-see: Paraplegic veteran surprises bride by standing for first dance

- Man found after being trapped inside store walls for days

- Suspects take selfies inside slain pastor's car

- Pat Sajak baffled by these Wheel of Fortune contestants

Not every American believes it is OK to always spank one's children, but a majority of Americans think it is sometimes "appropriate." In fact, 81 percent of Americans believe this, according to a new memo by the Brookings Institution.

That number tops similar behavorial findings in countries such as Canada (35 percent), the UK (41.6 percent) and China (50-60 percent). The US does lag behind Nigeria (91 percent) and Ethiopia (99 percent).

The comparisons are far from perfect. For example, the UK percentage doesn't reflect attitudes, but rather the parents who reported physically punishing or "smacking" their children in the last year. China's percentage reflects those parents who reported "using mild corporal punishment in the last month."

But: "Hitting children is more culturally acceptable in the U.S. than in many other nations – not only by parents, but by teachers (corporal punishment in schools is still permitted in 19 states)," write memo authors Richard V. Reeves and Emily Cuddy. "In many nations, physical punishment of children has now been outlawed."

Research shows that corporal punishment can be an effective behavioral tool in the short term, according to Brookings. But a countervailing body of research suggests that "children who are spanked regularly are more likely to be aggressive" (they begin to associate power with violence). Indeed, a 2007 study in the Journal of Family Psychology (published by the American Psychological Association) found that "most available research indicates that there are few, if any, positive developmental outcomes associated with [corporal punishment] beyond immediate compliance with a parent."

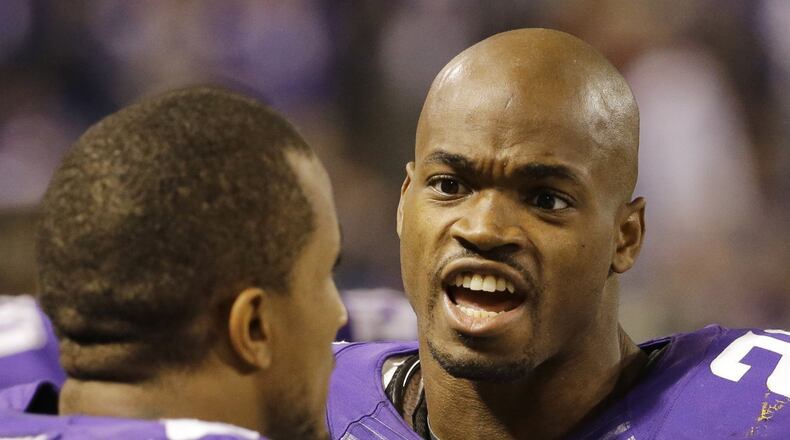

America's acceptance of the necessity of spanking — sometimes — may explain the nation's sudden disinterest in the case of Minnesota Vikings player Adrian Peterson, who was indicted in September for "reckless or negligent injury to a child," following a May incident in which Petersen allegedly beat his 4-year-old son with a switch.

The Peterson case spiked corporal punishment into the national conversation. But, according to a Brooking study of Google Trends, that interest fell within weeks.

>> More popular and trending stories

"Listen, we spank kids in the South," said former NBA star Charles Barkley, days after Peterson's indictment. "... I think Adrian said, 'I went overboard.' But as far as being from the South, we all spanked our kids."

In a September column, the AJC's Gracie Bonds Staples surveyed varying views on spanking.

“As a father of all girls, it’s easy for me to be against physical punishment because I don’t want to hurt my girls and because it doesn’t take physical punishment to get their attention when they’ve done something wrong,” said Cleve Gaddis from Atlanta. “My wife and I discipline our daughters by taking away some of life’s niceties like cell phones and cars or the freedom to spend time with friends. Fortunately for us, we don’t have to do this very often.”

The roots of this behavior seem simple: "Most of us either continue to parent pretty much the way our own parents did — as Peterson has confessed to doing — or we disliked the way we were raised so much we’re the exact opposite," Staples wrote.

But as the Brookings memo shows, the roots go deep.

About the Author